Diminishing and ever more costly supplies of steam coal are threatening a major crisis in the heritage railway sector. Nick Pigott’s book traces in depth the story of the fuel that fired the railway revolution, from early times to the present day.

The challenges of global warming have brought the once-unbreakable bond between steam and coal close to snapping – a situation considered unthinkable only a few years ago.

Faced with climate change, pit closures, high prices, green policies and now conflict in Ukraine, the heritage railway movement’s search for viable low-carbon alternatives to bituminous coal grows ever more urgent.

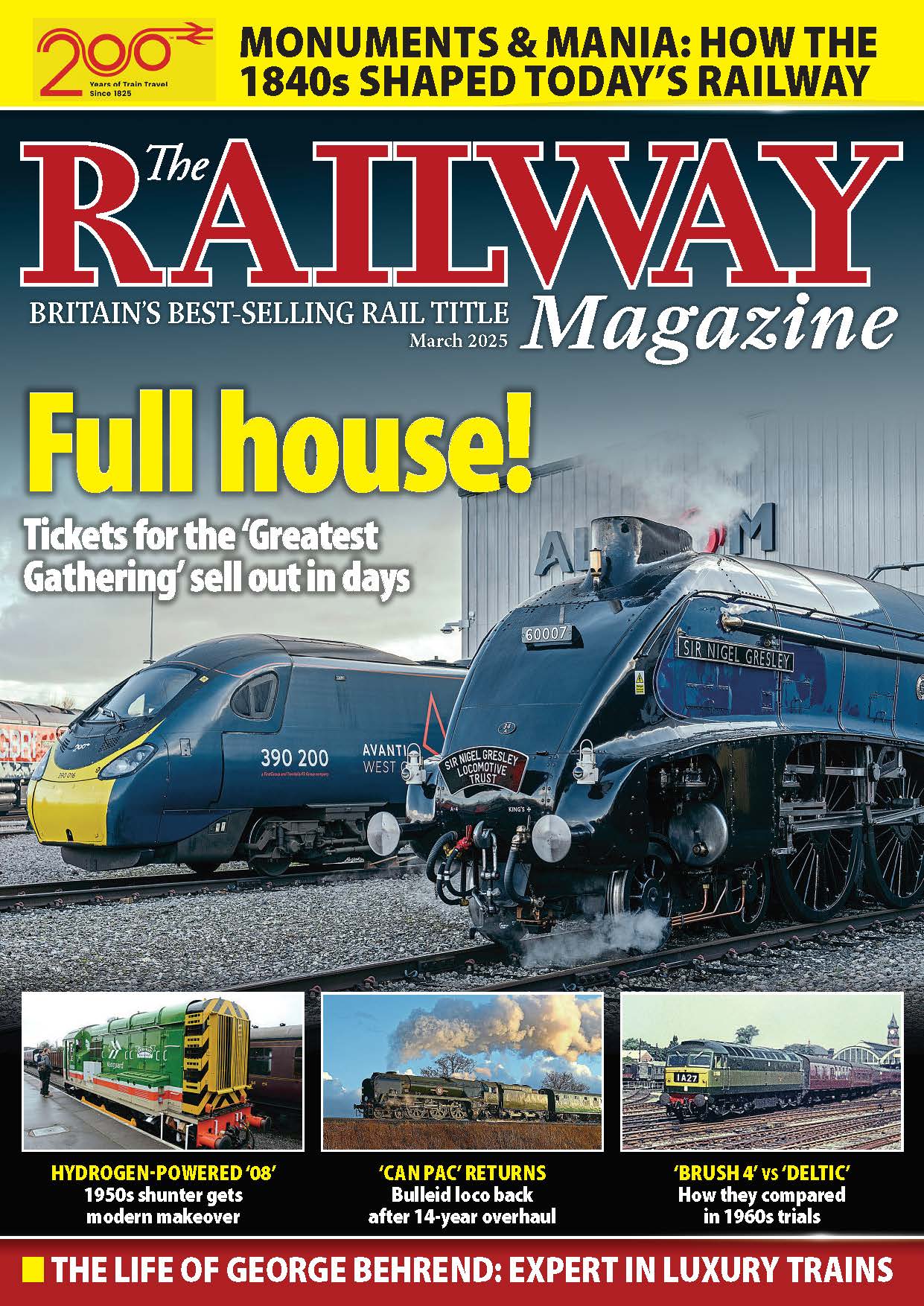

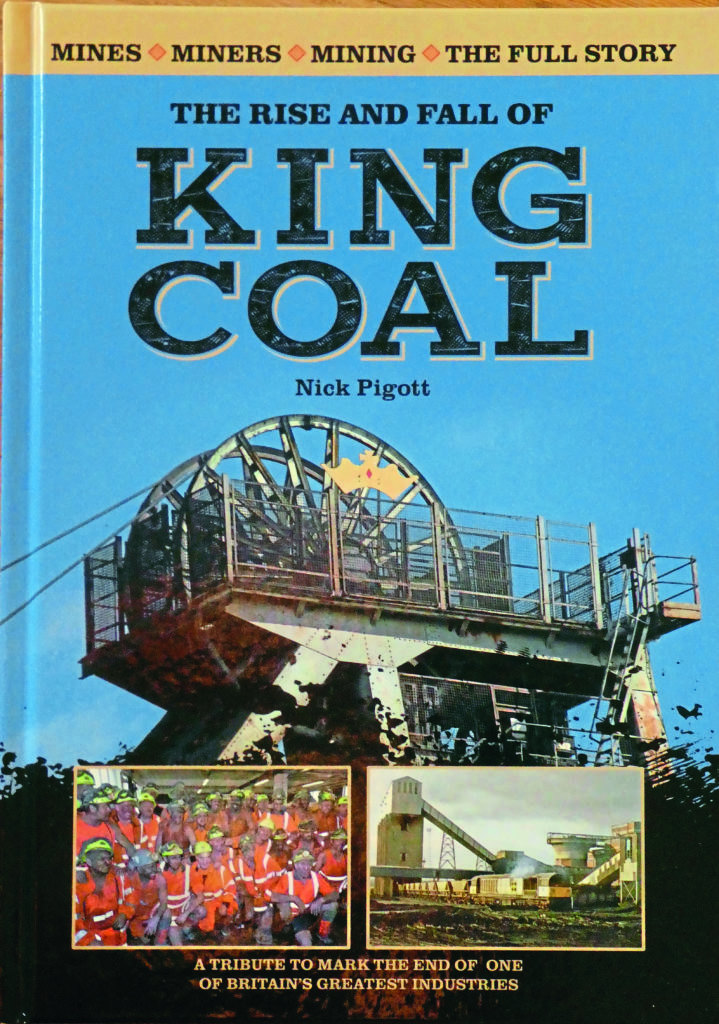

It’s a small wonder that many enthusiasts are turning their thoughts to the days when coal reigned supreme as the fuel that fired the Industrial Revolution and put the ‘Great’ into Britain. That golden age is recalled in The Rise and Fall of King Coal, published by Gresley Books and containing almost 300 illustrations, a third of which are rail-related.

Written by Nick Pigott, former editor of our sister title The Railway Magazine, the book is a tribute to mark the end of one of Britain’s greatest industries – a fully updated and enlarged hardback edition of a bookazine published in 2016 to mark the end of deep-shaft mining in Britain.

Beginning with the prehistoric origins of coal, the author explores the history and operation of a vast industry that at one time boasted nearly 3000 mines and employed well over a million workers. With the help of rare photographs and diagrams, the text explores the collieries, explains the locations of the coalfields, and examines the hazards, hardships, disputes and tragedies that were part of every miner’s life.

Railways, of course, came into existence primarily to convey coal, and until the advent of passenger services from 1830 onwards, the majority of steam engines had been built for mining or associated use. Development of the national rail network had the effect of opening up new coalfields, which in turn led to the establishment of factories and towns. Mine owners thus had to expand rapidly to tap into the new resources and feed the fast-growing offspring they’d conceived.

The natural affinity between coal and trains resulted in mutual dependence; the railway companies’ locomotive depots became big customers of the coal and coke producers. For more than a century, until the advent of reliable motor lorries, the mine owners needed the railways’ help to get their product into every factory, town, and village in the land. By 1924, British mines were producing 267 million tons a year and the railways were transporting no fewer than 225 million tons of that (84%).

Going underground

The 256-page book devotes separate chapters to surface railways, underground rail systems, and the heritage scene. Subterranean trains were known affectionately by miners as ‘Paddy Mails’, and the narrow gauge networks were remarkably extensive, often stretching three or four miles from pit bottom and featuring a wide variety of traction types, powered either by battery, flameproof diesel, or (in the case of half a dozen low-methane mines), overhead electric catenary. Diesel locomotives were allowed to work underground only if they had exhaust conditioners to remove toxic fumes.

On the surface, 4ft 8½in was the logical gauge for the movement of wagons to and from the main line network and purpose-built industrial 0-6-0 and 0-4-0 saddle tanks worked the vast majority of yards, although a number of pits used former Great Western pannier tanks and, later, pensioned-off British Rail diesel shunters.

Among the most unusual steam engines to work for the National Coal Board were two Beyer-Garratt articulated 0-4-4-0Ts – No. 6729 at Sneyd Colliery, Staffordshire, and No. 6841 at Warwickshire’s Baddesley Colliery, the latter locomotive now preserved. In the non-steam category, contenders for the most unusual included the white-liveried overhead electrics of the Harton Railway.

In addition to standard gauge tracks, the surfaces of many collieries in pre-skip winding days possessed narrow gauge systems with rail dimensions matching those of the tracks under ground. This was to enable tubs of coal to be moved from shaft top to weighhouse and washery and back again once emptied. Such lines were also used for storing wagonloads of roof supports and other supplies before they were taken below for onward movement to the coalface.

The book reports on the trials currently being conducted on UK heritage railways to evaluate various forms of biocoal and brings the energy story up to date with an analysis of the recent UN climate change summit in Glasgow.

The pledges made at that conference just six months ago looked set to consign coal (in the UK at least) to the pages of history forever, but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the unexpectedly early closure of Ffos-y-Fran opencast mine in Wales, and massive energy price rises generally have altered the picture out of all recognition.

As a result, the plans of Britain’s 150 or so heritage lines have been thrown into disarray. Galas, footplate courses, and even regular steam timetables are being cancelled or postponed as the railways struggle to meet crippling coal and diesel fuel bills.

There are even whispers that the Government might be forced to renege on its ‘green’ pledges and authorise the sinking of an all-new colliery near Whitehaven in Cumbria. Advocates of this rail-linked project point out that environmentalists opposing the scheme are doing so in the mistaken belief that it will be a thermal coal mine contributing to global warming through energy generation when in reality it is intended to produce only metallurgical (coking) coal necessary for steelmaking – an industry Britain needs to retain if it is to remain self-sufficient outside the EU.

It’s all a far cry from the relatively care-free days in which no one thought anything odd about steam locos laying dense smokescreens across their surroundings, or when photographers asked footplatemen to provide “lots of black clag” at scenic lineside locations. These days, it’s a brave magazine editor who sends a front cover depicting clouds of thick dark exhaust onto newsagents’ shelves. Not so long ago, that would have resulted in a sure-fire sales boost… how quickly life changes.

Halcyon days

Fortunately, plenty of fine old photographs survive to remind us of the halcyon days and a good selection is included in the book. Among locomotives and locations pictured are A4 No. 60009 passing Seafield Colliery, J38 No. 65901 at Rothes, Hawksworth 15XXs Nos. 1502 and 1509 at Coventry, J27 No. 65842 (somewhat incongruously) hauling a rake of new ‘Merry-Go-Round’ wagons and an 1822 Hetton locomotive remarkably still working in 1905, plus examples of Classes 20, 56, 58, 60 and 66 in a variety of mine and main line settings.

There are several photographs of underground man-rider trains too, including a Huwood/Hudsell Clarke diesel at Thoresby and a twin-pantograph electric machine at Gedling Colliery. There’s even a shot of a diesel loco being lowered in a vertical position down a mine shaft.

A chapter on museums and heritage sites brings up the rear of the book, illustrated with a shot of preserved locomotives at Blaenavon and one of former ‘Paddy Train’ carriages, in which the public can ride at the National Mining Museum near Wakefield.

With energy pricing and provision being in such disarray at the moment, the book ends by asking whether coal in some form or other might yet have a role to play in the Britain of the future, despite the many green pledges.

The Rise and Fall of King Coal by Nick Pigott retails at £29.99 and is available to order from www.mortonsbooks.co.uk

Advert