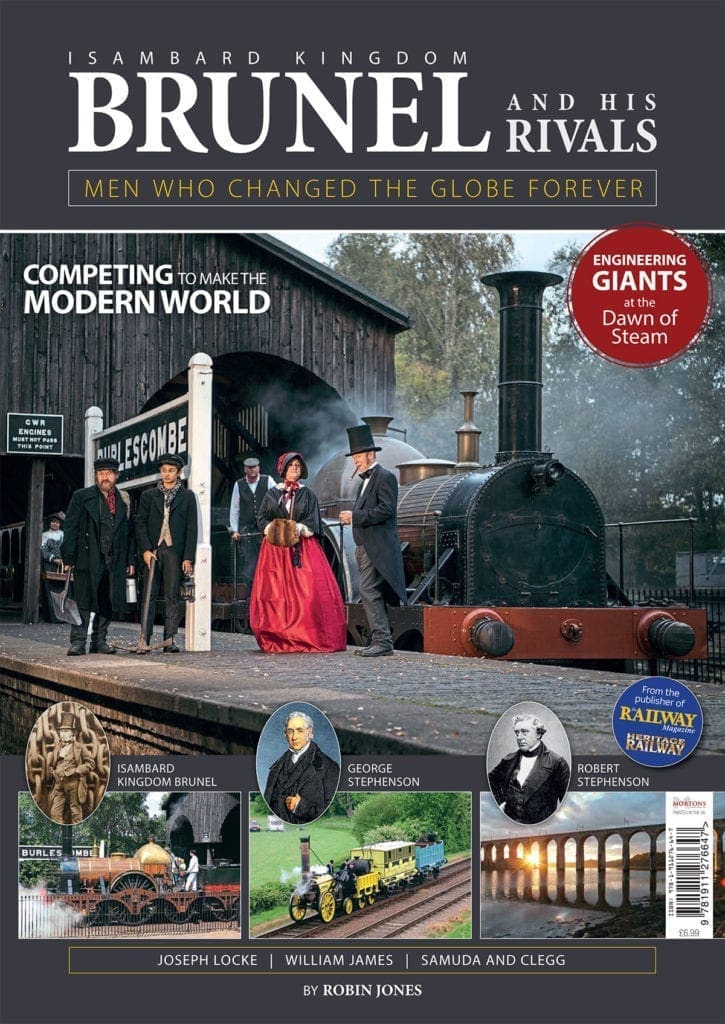

Engineering wizard Isambard Kingdom Brunel has continued to inspire and amaze generations long after his death in 1859.

It was on March 2, 2018, that a major museum was opened in the harbourside in Bristol, one of the world’s great waterfronts, at a cost of £7.2 million.

Being Brunel is the latest in a long line of tributes to the legendary engineering genius who, in a BBC public poll in 2002 to determine the 100 Greatest Britons, was voted the second greatest of all time.

Not bad for a man who by parentage was half French, and was pipped at the post only by Sir Winston Churchill (a man of mixed English and American parentage).

Being Brunel is dedicated to Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the legendary engineering genius who became the figurehead of the great period of technological progress that followed the Industrial Revolution.

Of course, nothing could ever equal a monument to Isambard Brunel that would better any of his magnificent feats and structures – Box Tunnel, the Royal Albert Bridge at Saltash, the original Bristol Temple Mead station, the nature-defying coastal railway route between Exeter and Teignmouth, Clifton Suspension Bridge, Maidenhead Bridge, and many, many more, last but by no means least being the Great Western Railway.

Being Brunel, which stands just a few yards away from Isambard’s iconic SS Great Britain, is a modern new gateway to understanding much more about the great man. The new visitor attraction features six galleries showcasing around 150 of Brunel’s personal artefacts, many of them never displayed in public before,

to give an unprecedented insight into his life, family, interests and creative mind, a mind and sharp talent which fellow engineers of the day sought to emulate and rival.

The age of Brunel – the first half of the 19th century – was a classic “can do” time, when the Industrial Revolution blossomed with fruits aplenty, and there were many who sought to shake the ripe apple trees.

The invention of the self-propelled steam locomotive by Cornish mining engineer Richard Trevithick in the first years of the 19th century did not take off overnight by any means. Indeed, horse traction remained the popular option as far as general state-of-the-art traction was concerned for the next quarter century, and Trevithick died in poverty in 1834 despite his globe-shrinking invention, but such innovations set minds thinking and imaginations running into overdrive.

Each time technology moved forward by an inch, its sum total would give the likes of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and his rivals an extra mile in which to experiment and explore. Each scientific nudge forward showed the world it did not always have to be the same as it always had been, but could be a better place.

Cometh the hour, cometh the men – and young Isambard was at the forefront of the global steam revolution, a man widely considered to be ‘one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history’…and who would remain in competition with the best of his day.

Going Underground

So who was this engineering wizard? Isambard was born on April 9, 1806, two years after Trevithick gave the first public demonstration of a railway locomotive at the Penydarren Tramroad, near Merthyr Tydfil.

He was the son of French civil engineer Sir Marc Isambard Brunel and English mother, Sophia Kingdom and was born in Britain Street, Portsea, Hampshire, where his father was working on block-making machinery.

His first name Isambard came from his father, a Norman name of Germanic origin meaning “iron axe”.

Along with his two elder sisters Sophia and Emma, his parents moved the family to London in 1808 when his father gained a new job.

The family were often short of money but nonetheless resourceful. Marc doubled up as his son’s teacher in the earlier years, educating him in drawing and observational techniques from the age of four; indeed, Isambard had learned Euclidean geometry by the age of eight, along with the basic principles of engineering. He was encouraged to draw interesting buildings and identify any faults in their structure.

A fluent French speaker, at the age of eight he was sent to Dr Morrell’s boarding school in Hove, where he learned the classics. Marc was determined his son should the high-quality education he had enjoyed in pre-revolutionary France.

When he was 14, Isambard was sent across the English Channel to complete his education, firstly at the University of Caen, in Normandy, and then at Lycée Henri-IV in Paris.

A year later, Marc ran up debts of £5000 – and was sent to a debtors’ prison. However, the Government paid off his debts after Marc let it be known he was considering an offer of a job from the Tsar of Russia.

Isambard’s studies at Henri-were completed in 1822 and he took an apprenticeship with the prominent master clockmaker and horologist Abraham-Louis Breguet, who praised his potential in letters to Marc.

Isambard came back to England later that year and soon found employment on a world-changing feature of engineering. Between 1825 and 1843, he worked on the project to create a tunnel beneath the River Thames between Rotherhithe and Wapping for use by horse-drawn carriages.

Brunel and his Rivals

Fancy reading the full version? Order a copy of Brunel and His Rivals from Classic Magazines here.