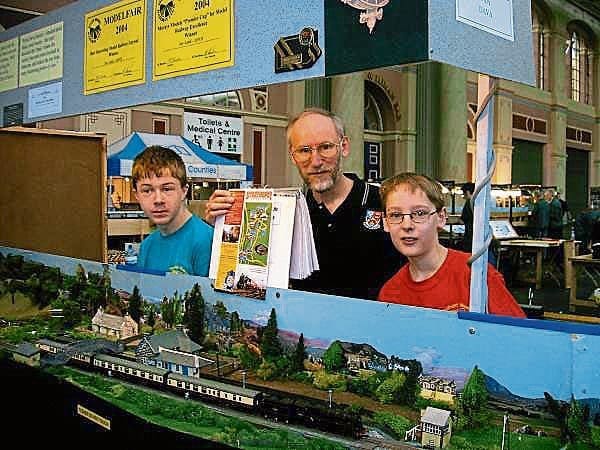

Most of Ian Lamb’s railway modelling has been undertaken in order to encourage young people to take up the hobby and thus ensure the passing-on of skills. Ten years ago, under his guidance, a young Stewart Burr offered to reconstruct a badly damaged section of the ‘Dava’ project layout as part of his Silver Duke of Edinburgh’s Award. This is how he accomplished it.

The ‘Dava’ Project Group had been exhibiting at the annual Inverness Exhibition since 2009, but at the end of that year’s event, the weather was so bad that one of the sections was so severely damaged while being transferred to the van that it needed an almost complete rebuild.

Weather damage apart, after around 20 shows some of ‘Dava’s’ scenic work was becoming a little tatty in any case, so Stewart asked if he could take on the necessary work for the Castle Gatehouse section as part of his Silver Duke of Edinburgh’s Award Skills Programme to get it up to exhibition standard in time for The Model Railway Club’s Centenary Exhibition at Alexandra Palace in London in 2010.

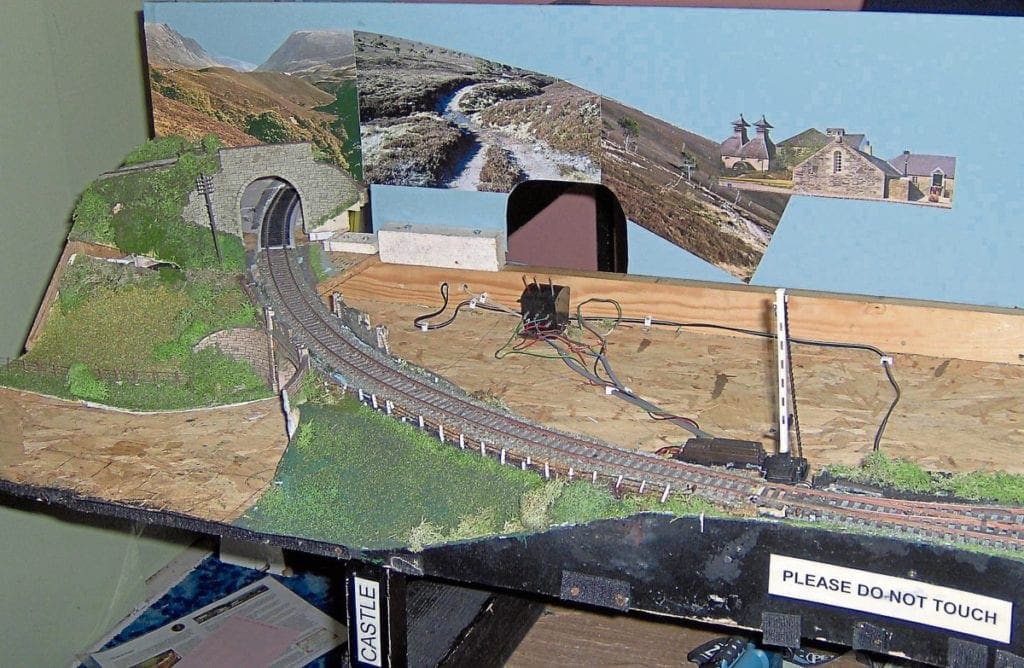

Stewart said: “The first job was to strip everything out and salvage what I could, preparing the back board from scratch and covering it with ‘sky’ paper.

“Meanwhile my father and Ian Lamb were completely rewiring this section, mainly to enable the relevant point and signals, which used to be changed by hand, to operate by remote control.”

As it was neither practical nor the best use of time for everyone to meet weekly for an hour or so to pursue this work, the meetings took place at roughly monthly intervals where much more could be achieved from the accumulated time. By mid-December 2009 it was possible to take the section home, where Stewart could work on the model more easily and complete the finishing touches whenever he had the time.

“While I was working on this section,” he said, “I undertook a fair amount of research into the local landscape in order to incorporate the main elements on to the model. Indeed I used photographs printed on matt photo paper, one of them from my Expedition Assessment venture, as part of the back scene. The sky was trimmed out of the photos using a knife, and the photos were then fixed to the backdrop with PVA glue.

“Lots of time was now spent in creating the illusion of distance within a true Highland atmosphere, as would have been experienced by any traveller on the line when it was in existence. The integral part of the section is the road running under the bridge and into the distance, so this was fixed in place using card formers every couple of inches for strength. The hills were then built up around the road using card formers to get the initial shape and to add strength to the overall structure (this being a weak point of the previous section). These were filled with scrunched-up newspaper that was glued loosely into place.”

It was decided to use plaster to cover the hills – again to aid the strength of the overall layout. Plaster was then brushed with a generous amount of water to make it fix to the newspaper and formers below. This action was repeated until the desired effect was achieved, a major advantage of plaster being that adding more layers simply increases the strength. Once completed, the plaster was painted in a dark brown colour before any scenic materials were added so that the white base card would not show through.

This part of the Highlands at the foot of the Cairngorm Mountains has one of the few remaining natural forests of ancient Scots Pine, so it was essential that at least one of them found its way on to the layout. This also serves as excellent cover for the join between two back scene photographs. Stewart used one of the new Hornby ‘Skale Scenics’ professional trees [R 8927], but fitting it to the right of the tunnel entrance was quite a challenge.

For a start, the tree was about 30mm too short, so a piece of dowelling was found for the trunk to fit inside and a hole drilled to make it possible (the dowelling was not trimmed to the right length at this point). Then a hole was made in the plaster and the tree ‘planted’ through.

A block was attached to the baseboard below and another hole, the same diameter of the dowelling, was drilled. This was then filled with epoxy resin and, with it cut correctly, the dowelling was fixed in the right place. Where the tree poked through the plaster, more scraps of filler were used around the base of the tree to hold it in place. This meant that the tree is fixed in two places, so is very strong.

The piece of dowelling above the plaster and the surrounds were then painted a dark brown to match the tree. The bottom of the tree would be later surrounded by lichen anyway so it didn’t matter if the join – between tree and dowelling – was noticeable.

Stewart continued: “The essence of the ‘Dava’ Project, which has applied ever since I attended the first workshop almost 10 years ago, has been to create as much of the model as possible from scrap material, and I bore that point in mind when constructing the required scenery.

“The fences, like the one to the left of the tunnel entrance, were made from matchsticks and cereal box card. Two strips of card were cut thinly to represent cross-members to the desired length, and it was decided that the fence posts (six in this case) should be roughly 30mm apart. All parts were painted dark brown before assembly, holes were made in the baseboard and the matchsticks were fixed into place.

“One of the long strips of card was then fixed into place and glued to the fence posts, and the process was repeated for the second strip. The fence was left deliberately in quite a ‘rough’ state, with some parts slightly too long or too high as would have been the case in the middle of a Scottish moor, and made with whatever was available.”

A touch of real soot gives an authentic impression of the tunnel portal, and for a while Stewart played around with clusters of lichen creating bushes and undergrowth, especially around any areas adjoining the back scene. “This was necessary to ensure that we had the balance just right between depth of field and a narrow defile. At this stage it was envisaged that a fair amount of open country, perhaps a field, should be represented in the middle ground, but for the moment it is all simply grassed over while the landscape round the real castellated bridge is studied so that the model can reflect this as far as possible.”

Priority was then given to completing the castle gatehouse section. “As with any model venture, it is essential to use an authentic photograph,” said Stewart, “but even more so in this instance because the castle gatehouse is an icon of reference to the overall project. It existed before the railway came, and still stands today with its castellated bridge to remind us that the one-time Highland Railway main line once crossed here.

“The original model of the gatehouse had been damaged, so rather than replace it completely, Ian Lamb just repaired and renovated it.”

In the end, an appropriate model tree to complement this architectural gem was chosen from the early days of the layout. This had been made from scratch utilising a twig and rubberised horsehair, suitably adorned with green scatter material!

This tree was in a vulnerable place so needed to be well secured, and as the board was double thickness here, it was decided that it should be both glued and screwed. A hole (the diameter of the tree) was drilled through the top half (about 16mm) of the baseboard so that the tree would sink into the ground. A smaller hole was then drilled through the bottom half of the board (another 16mm) and into the bottom of the tree. The edge of the larger hole (i.e. the one on top) was then filled with epoxy resin so as to give a strong and fast-setting hold. This handmade tree was then sunk into the hole and a counter-sunk screw was screwed in from the bottom (through the smaller hole) and into the base of the tree. This gave the secure footing needed.

“Once the rebuilt castle gatehouse had been added, this corner of the overall layout became even more attractive than the original section ever was,” said Stewart. “Fitting the granite dyke (wall) and fencing brought the whole diorama together nicely, and I think I’ve achieved what I set out to do, and now, with full attention to detail, it needed only the finishing touches. What a pity I cannot create a whiff of whisky aroma being blown down wind and the deep whistle of a ‘Black Five’ as it thunders uphill to Dava Summit! However, there’s a limit to what can be constructed!

“I’d like to thank Nick Freezer, MRC London, for assessing my work when it was on display at Alexandra Palace, and signing my Silver Duke of Edinburgh’s Award record book.”

A decade has passed since Stewart undertook the ‘Dava’ project layout section repair, and though that layout won’t be at ‘Ally Pally’ next March, the current beginners’ layout ‘Chawton’, which enables many young people to have a ‘hands on’ experience of a model railway, will be.

After leaving school, Stewart went ‘furth of the Highlands’ to Strathclyde University in Glasgow to study engineering, and obtained a Masters of Engineering degree. He continued south to Winchester, where he now works as a design engineer.