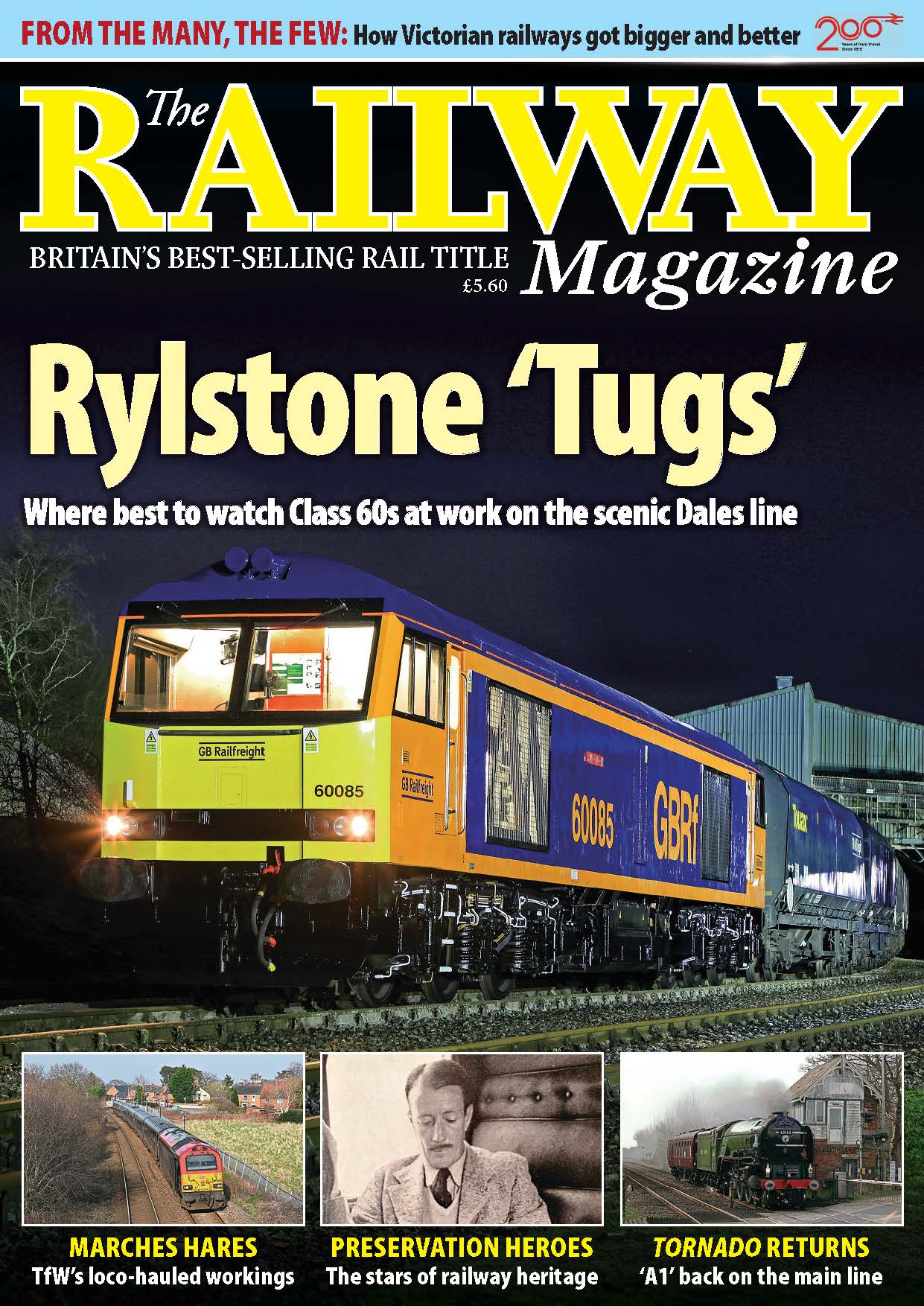

In the 1990s Virgin saw a future in UK railways and secured one of the highest profile rail franchises. 20 years on it has transformed travel but for the first 10 years it was a tumultuous ride.

Steven Knight, who for more than 12 years was part of Virgin Rail’s media, staff and stakeholder communications team, reflects on the last 20 years.

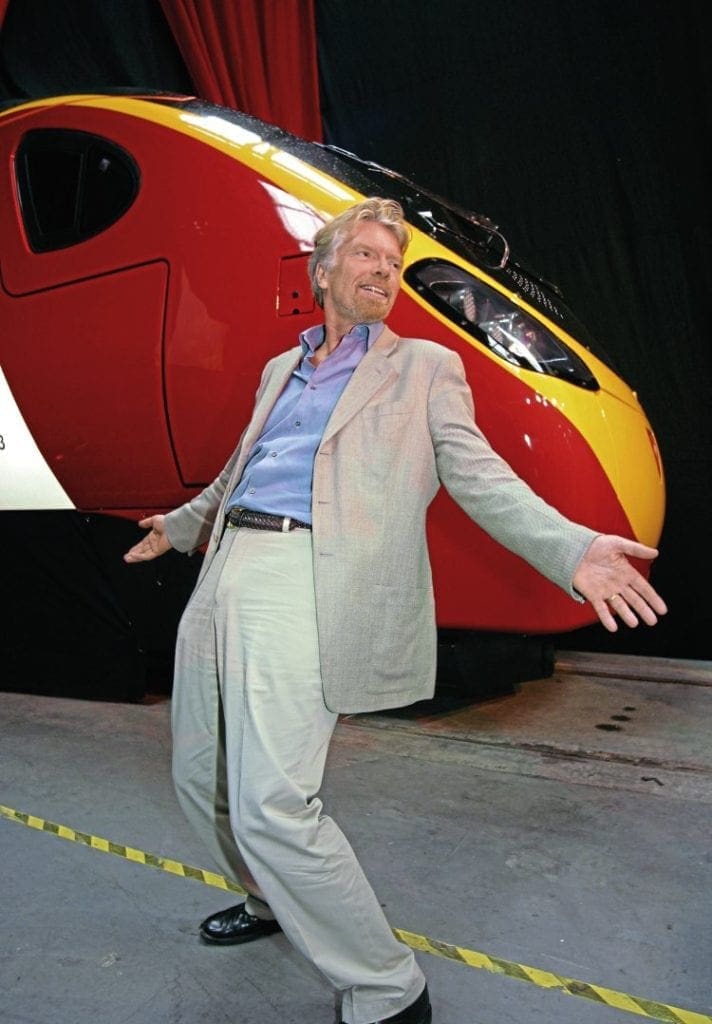

It was in the early 1990s the Virgin empire with (now Sir) Richard Branson at the helm first tuned its thoughts to UK rail. In fact the idea pre-dated the Privatisation of British Rail.

Virgin had been seeking an open access operation on the East Coast to run a limited high-quality business service between Edinburgh-Newcastle-London. It was, however, the Privatisation of Britain’s railways that gave Virgin its springboard into UK Rail and put it on a roller coaster ride.

Sea Containers won the InterCity East Coast franchise, one of the earliest, which started in February 1996. Virgin’s focus was elsewhere at the time but soon returned to rail. Sea Containers, through its GNER subsidiary, would prove to be a formidable rival to Virgin.

Virgin scooped CrossCountry from January 1997, which it operated until November 2007, and then West Coast, which it formally took over at 02.00 on March 9, 1997.

As was expected from Virgin – which had won the franchise for a 15-year term – there was a high-profile launch for West Coast, with new uniforms for staff and a train in Virgin colours on day two of the franchise.

Virgin would have preferred to only put its name on the trains at the start of the franchise, but the Office of Passenger Rail Franchising forced the issue on repainting the trains red.

Partnership

A partnership approach with Railtrack and Fiat Ferroviaria promised 140mph ‘Pendolino’ trains on a completely upgraded railway. To maximise its investment Virgin was protected from competition on the route until 2012.

Fiat Ferroviaria was subsequently bought by Alsthom, which later dropped the ‘h’ from its name to become Alstom. However, within hours of the West Coast franchise starting there were industrial relations issues. Virgin was already running the CrossCountry franchise and set about streamlining the management structure into one corporate organisation.

With many CrossCountry staff already in post, the axe was wielded across West Coast.

Externally, the Virgin hype had in the eyes of many passengers and commentators over promised on its improvement commitments.

The shiny red trains on the outside were masking the fact nothing had changed underneath. Reliability continued to be poor, and Brian Barratt, who worked on the franchise bid and was appointed chief executive, faced an uphill battle.

The performance issues came to a head in October of the following year when a train from Euston carrying Labour party politicians to their annual conference was delayed because of overrunning engineering works and a myriad of ongoing operational problems. One of those delayed was John Prescott, who immediately said Virgin should lose the keys to its franchise.

It was unfortunate West Coast was viewed in such a negative way, since there was a great deal of positive developments. Having pioneered telesales, Virgin had taken this a step further and established an internet booking service through its own company – Trainline. Alongside this plans were being formulated for the fleet of tilting trains and a complete route upgrade.

On a further positive note, through services were restored from London to Shrewsbury and also from London to Blackpool.

Initially, Virgin’s rail activity was funded through arrangements using venture capital, with Virgin having a 41% share. Several options were explored to repay the venture capitalists, including floating Virgin Rail Group on the Stock Exchange, but a different route was taken when Stagecoach became a 49% partner in October 1998, with Virgin having a 51% share.

Ambitious

The plans were ambitious. The West Coast would generally remain open while most of the upgrade work was completed. The first stage by 2002 would allow trains to operate at 125mph and the more ambitious second stage in 2005 would allow 140mph operation using moving block in-cab signalling. The cost of the upgrade was initially put at £2.5billion, but soon reached in excess of £10bn.

Working with Angel Trains and Fiat Ferroviaria a contract was placed in 1999 for 53 ‘Pendolino’ trains, of which 44 had eight coaches and the remaining nine were nine-coach. There were also four four-car tilting ‘SuperVoyager’ trains ordered as part of the CrossCountry new train order, which would be used on the London to North Wales route.

Virgin also worked with Porterbrook to develop the Class 57/3 diesel locomotive, a rebuild of Class 47s, to provide sufficient hotel power to both power onboard systems and haul ‘Pendolino’ trains at times of train or power failures, and on routes away from the overhead line.

Investment in the railway continued and besides the through services re-introduced to Shrewsbury and Blackpool, refurbishment of the inherited train fleet and improvements at the VT-managed stations was taking place.

However, despite the huge investment in the background, Virgin was still suffering.

Perception of the operator was poor, even if the reality was somewhat different.

Richard Branson turned to respected railwayman Chris Green, who was parachuted in as chief executive in 1999. Chris’ role was to ensure there remained a day-to-day management focus on the business while the transition to an upgraded railway took place.

It was, however, events of October 17, 2000, that brought about a change on the railways that could have seen the end of Virgin’s West Coast dream in its entirety.

The fatal accident at Hatfield on the East Coast Main Line had far reaching consequences across Britain’s entire rail network. Caused by rail fatigue, Railtrack imposed speed nationwide restrictions while it checked, and repaired, the railway infrastructure. Journey times were significantly increased and passenger numbers fell.

The re-introduced through London to Shrewsbury train was axed as the rolling stock was needed for core West Coast services.

In the wake of Hatfield it became clear Railtrack could no longer fund its commitments to the West Coast Main Line. The 140mph option was off the agenda and even the completion of the 125mph upgrade was uncertain.

Virgin was faced with a dilemma. Its business case was in tatters. It was not ready to walk away, however, and there was talk of legal action against Railtrack for breach of contract, and discussions were underway with the Government around a compensation package.

In the event it didn’t get to that stage as on October 7, 2001, Railtrack was put into administration by then Transport Secretary Stephen Byers and replaced by the not-for-profit Network Rail.

Despite the downturn in business, Virgin was confident the business would return and ordered 44 additional ‘Pendolino’ vehicles to make all 53 ‘Pendolinos’ nine-coach sets.

The first ‘Pendolino’ carried fare-paying passengers between Birmingham and Manchester on special services for the 2002 Commonwealth Games.

Behind the scenes, Virgin saw its franchise, which was held on commercial terms, replaced by the ‘Letter Agreement’ – a management contract. However, with the golden carrot of returning to a commercial arrangement dangled, it put all its efforts in to delivering an upgraded railway.

‘Red Revolution’

The revised plan was for a tilting timetable, dubbed ‘Red Revolution’, to launch in September 2004, with a step-up in frequency taking place four years later.

A further four Class 57/3 locomotives were ordered to enable hauled ‘Pendolinos’ to replace the HSTs used on London to Holyhead services. Just nine months after the ‘Red Revolution’ launch the last of the ‘old’ trains were taken out of service, although one set was to later return for relief and charter use.

Between 2000 and 2004 the media continued to attack Virgin Trains for its poor performance, high levels of customer complaints and increases in fares. The West Coast operation was rarely out of the headlines.

A concerted effort by Chris Green and his media team, however, meant the positive messages on new trains, planned journey time reductions and increases in frequency were also in the media. The messages also focused on Virgin’s biggest asset – its people.

Stakeholder engagement was a key strategy with events across the routes to promote the new trains and journey opportunities while making local communities feel part of the transformation. It was also important to get the messages understood by passengers who would face further years of disruption as the upgrade work took place.

Perhaps the biggest impact on awareness came from the media and stakeholder

events that were organised to showcase ‘Red Revolution’, which included a number of train namings. Then came the ‘Red Revolution’ launch proper in 2004 with a spectacular event at London’s Euston station involving then Prime Minister Tony Blair.

A record run to Manchester followed and on the return a further speed record was achieved – just over 1h 53 minutes, knocking around 50 seconds off the northbound record time of 1hr 53 minutes and 52 seconds.

2004 really was a turning point. Media coverage started to be balanced rather than negative, although engineering works, fare increases and performance, along with perceived smelly ‘Pendolino’ toilets, continued.

That year also heralded a new chapter for Virgin West Coast. Tony Collins, who had headed up the major contracts part of the business, became chief executive. Tony was able to direct the business focus on ensuring ‘Red Revolution’ was able to deliver the company’s promises. The business went from being one that was project driven to one that was business and customer driven.

While the West Coast swan was graceful on the water, below the surface it was a challenging time. With 140mph operation a distant and forgotten dream, the focus was now on the Virgin High Frequency (VHF) timetable that would allow up to 11 Virgin trains an hour into and out of London’s Euston station. Journey times would also be reduced and three trains an hour would link London with Birmingham and also Manchester.

An hourly service would operate from London to Glasgow, London to Liverpool and London to Chester, with some of the Chester trains continuing to Holyhead. Additional trains on the Glasgow and Liverpool routes were timetabled for peak times. VHF would also deliver a truly seven-day-a-week railway.

Glitzy

Staff and stakeholder briefings were the key to VHF rather than the glitzy media and PR events that had taken place in the past.

A concession was a demonstration of the speed-improvement potential on the Glasgow to London route. A special charity train on September 22, 2006, organised in partnership with The Railway Magazine, saw a ‘Pendolino’ cover the 401miles in 3hr 55min and 27sec – a record for a southbound train carrying fare-paying passengers.

The high-speed run was a concession to the ‘low key’ launch being planned for VHF.

However, as planning for VHF was underway the Virgin team had to face the unthinkable: the tragic derailment of a ‘Pendolino’ train because of faulty track, near Grayrigg, on February 23, 2007.

Following the loss of the CrossCountry franchise in 2007, the Birmingham to Scotland service via Preston passed to West Coast. The ‘SuperVoyager’ trains transferred also allowed ‘Pendolinos’ to be taken off North Wales services.

The VHF timetable came in as planned in December 2008 and was immediately well received and created additional capacity .

Further capacity enhancements were to follow with an order by the Department for Transport for 106 additional ‘Pendolino’ carriages.

This included four new 11-coach ‘Pendolino’ trains and additional coaches to increase 31 of the 52 ‘Pendolino’ trains to 11-coach, while a First Class coach on the remaining 21 nine-coach ‘Pendolinos’ had been converted to Standard. This project was completed in 2012.

The Virgin West Coast story could have come to an end in 2012 when the franchise to run services on the route was awarded to First Group.

Virgin called for a review of the franchise award process and started proceedings for a legal challenge. At the same time a public petition was launched through the Government website to secure debate time in Parliament.

The fact the petition succeeded with more than 175,000 signatures was a real indication Virgin had come good on the route and had the support of its passengers. In the event the franchise decision was reversed and Virgin was awarded a franchise, which has subsequently been extended.

It now expires in 2018, with a direct award through until 2019 expected prior to the start of a new franchise, which will dovetail into the start of HS2 operation.

Respected

Tony Collins retired from Virgin Trains in 2013 and since then Phil Whittingham has been at the helm as chief executive.

A respected contract negotiator, Phil is seen as a steady pair of hands. He has been able to keep an overview on Virgin’s relationships with Network Rail and the DfT while also keeping an eye on franchising issues and ensuring the service and facilities provided to passengers continually evolves.

In 2013, one of the three London to Birmingham services an hour was linked into the hourly Birmingham to Scotland route to provide two through London to Scotland services an hour. The following year through trains were restored from London to both Shrewsbury and Blackpool.

The Virgin Group has a pedigree in innovation and being first so it comes as no surprise it was the first train operator to introduce wi-fi onto its trains, and also to have an at-seat entertainment system and electronic seat reservation details.

In 2015 it became the first train operator to offer automatic compensation payments for train delays where passengers buy advance tickets through its own website.

It has pioneered mobile ticketing for all types of tickets, and for passengers at Euston it offers an early-bird notification by text message of train-boarding information before it appears on the main station departure boards.

In 2016 it launched BEAM, an onboard entertainment app which offers movies, TV shows, magazines and games.

In 1997, West Coast carried 15 million passengers a year. Now, 20 years on, it’s 37m and rising. Daily performance is more than 90% on a regular basis. Market share on the Manchester to London is now 91%.

Virgin rarely makes the national and local media with negative headlines on a daily basis, and relationships with industry partners are the best they have ever been.

However, the most important statistic is how Virgin’s own passengers view the business, and the company’s research continually shows Virgin Trains on the West Coast ranks among the leading customer service-experience providers in the UK.

The last word goes to Virgin founder Sir Richard Branson: “Twenty years ago, when we took over West Coast, we called the challenge ‘mission impossible’.

“The idea that we could transform West Coast was met with scepticism and ridicule, but over two decades later we’ve established ourselves as a key part of the rail landscape.” ■

The Railway Magazine Archive

Access to The Railway Magazine digital archive online, on your computer, tablet, and smartphone. The archive is now complete – with 122 years of back issues available, that’s 140,000 pages of your favourite rail news magazine.

The archive is available to subscribers of The Railway Magazine, and can be purchased as an add-on for just £24 per year. Existing subscribers should click the Add Archive button above, or call 01507 529529 – you will need your subscription details to hand. Follow @railwayarchive on Twitter.