As the year of celebrations marks 200 years since the opening of the Stockton & Darlington Railway in 1825, Dr Joseph Brennan details the pre-S&DR railway ‘firsts’.

This year marks Railway 200, the 200th anniversary of the birth of the modern railway, occasioned by the opening of the Stockton & Darlington Railway (S&DR) on September 27, 1825. But what exactly was birthed on that day? The S&DR was not, for example, the first railway to be constructed following an Act of Parliament. It was also not the first to use malleable (wrought) iron rails; not the first public railway authorised; and not the first to use a steam locomotive to pull passengers.

In short, the S&DR was not remarkable for use of a new technology or mode of traction. “Instead,” as David Knight explains in a 2021 Historic England (HE) report, “the importance of the S&DR lies in the fact that in 1825 it brought all of these developments together, offering the world’s first steam-locomotive public railway service.” But even this statement, as we shall see, is not without its challengers.

This article tracks each of the aforementioned firsts, plus some other interesting milestones along the way. Rather than contesting the significance of the S&DR, this survey will add richness to the railways’ portrait, putting the triumph of the S&DR achievement into context, giving colour and credence to the 200-year milestone.

First following an Act of Parliament

Middleton Railway (1758)

In 1758, the Middleton Railway in Leeds became the first railway built under its own Act of Parliament. Charles Brandling was responsible, with the railway built to supply the city with coal – unusually for an early railway, not connecting with navigable water.

The MR continues to run today as a heritage railway, calling itself the “World’s oldest continuously working railway”. On its early history, wooden rails were used here, with these being replaced by cast-iron edge rails around 1799. We will return to the MR later in the story for another ‘first’, but for now, on the switch-to-iron rails front, Coalbrookdale has this title from 1767.

First use of iron in rails

Coalbrookdale Ironworks Railway (1767)

It took until the second half of the 18th Century before not just rails but practically all components of a railway made the shift from wood to iron.

In this regard, and rather fittingly, the Coalbrookdale Ironworks Railway was a real pioneer at the dawn of rail’s iron age (in a similar way to which the USA’s great concrete transporter the Lackawanna Railroad made pioneering use of the material it carried for its awe-inspiring viaducts in the Edwardian period). Indeed, Coalbrookdale would also cast the world’s first iron bridge, the Grade 1-listed bridge spanning the River Severn that opened in 1781 and still stands today as a leading light of the Industrial Revolution.

Coalbrookdale was keen to bring iron into play on its railway, it being 1729 that iron wheels have been earliest recorded here; while the incorporation of iron into rail design was also pioneered there around 1767. Interestingly, it was the famed botanist Joseph Banks (who sailed to the South Pacific with Captain Cook on board the Endeavour in 1768-1771) who adds credence to the iron-first claim of Coalbrookdale. Banks observed, in 1767, that the oak rails on the railway had worn out, to be substituted for cast-iron upper rails.

The process involved laying iron strips along the top of the wood on extant railways leading to the Severn and the road system, which came to be called “strap rail.” The use of cast-iron plate-rails followed in 1786, while confirmation of all-cast-iron edge rails was first recorded in South Wales in 1787. Coalbrookdale was then carrying steam locomotives by 1802.

The Newdale Tramway bridge in Lawley and Overdale, Shropshire, is an important relic of this railway. With its two small arches of brick over a stream, it survives in remarkable condition. Grade II-listed, it is described by the authority as “virtually all that remains of the large network of tramlines that existed in the area during the Industrial Revolution”. Dating from around 1759, it carried an early plate railway from Coalbrookdale via Horsehay and Ketley to Donnington Wood, and was used for transporting materials to and from the ironworks at Horsehay. If I were to tap a bridge for a listing upgrade, it would be this one.

First public railway authorised under its own Act

Surrey Iron Railway (1803)

The Surrey Iron Railway (SIR) opened in 1803 as England’s first public railway to be authorised by Parliament independent of a canal, and thus the first railway company. It set itself apart from other early railways – those built privately and with use restricted to the sponsoring company – by, significantly, allowing a general use of its tracks. The SIR provided the track while wagons could be hired for a toll.

With its first phase known as the ‘Surrey Iron Road’, canal builder William Jessop engineered the line and George Leather was resident engineer. The double-plateway configuration ran for around eight miles from a Thames wharf at Wandsworth through Tooting and Mitcham to Pitlake Mead in Croydon, with branches to industrial undertakings including to oil-cake mills at Hackbridge.

The SIR was horsedrawn and carried only freight, operating through to 1846 when horse-drawn railways were superseded by steam railways. Excitingly, parts of the SIR survive in the form of earthworks (cuttings) and even a short section in Wallington, Greater London, comprising a small number of iron rails attached to stone sleepers listed at Grade II. The walls of the Ram Brewery in Wandsworth have also done their bit to preserve history, having set SIR stone sleepers into the wall, situated on the road that the railway once ran along. A plaque above the sleepers explains their significance.

Many readers will naturally draw parallels here with the run of exposed in-situ sleeper stones at the S&DR Brusselton Inclines in Shildon, County Durham. Running for more than 110 yards (100 metres), these form part of an S&DR Scheduled Monument.

On the SIR heritage trail, you will also find a tantalising rumour. It was “formerly said” – to use the language of the listing authority – that the Grade II-listed Mitcham station on London Road had “been built for the horse drawn Surrey Iron Railway of 1803”. If what was “formerly said” true, then this building would have a claim to be the world’s first station building. Tracing this rumour in local folklore would make for an interesting historical deep dive for any Mitcham historian. Also known as Station Court, we do know that the building served the Wimbledon & Croydon Railway from 1855, after that company took over the SIR line, the station eventually closing in 1997 when the line was converted to tram use.

Whether the Mitcham rumour turns out to be true or not, there was excitement in 2023 when a newspaper report from September 1827 emerged that clearly shows the building at the S&DR’s Heighington and Aycliffe station (which today is simply called Heighington) fulfilling the main functions of what later came to be recognised as a railway station. It had previously been thought to have been completed in the mid-1830s, the new evidence elevating it to a Grade II* listing, which puts it in the top 10 percent of England’s historic buildings and led Historic England to name it as the “world’s first railway station”.

First authorised to carry passengers

Swansea & Mumbles Railway (1807)

Wales continued to show itself as fertile ground for railway enterprise when the Swansea & Mumbles Railway – built as an industrial horse-drawn tramway in 1804/05 – became, in 1807, the first authorised to carry passengers. The original line ran from Swansea to Oystermouth, with horses continuing to power the railway until 1896 – though steam locomotives were incorporated in 1877.

The industrial origins of the railway are captured by this 1819 description from Abraham Rees: “Along the shore hence to Swansea, a railway has been constructed, by which coals and manure are brought down, and lime returned from the limestone quarries, which are situated close to the village of Mumbles, and where several lime-kilns are established.” But it was, of course, the carriage of passengers that was most remarkable here and would foreshadow much of the railways’ future promise.

On exploring new possibilities, it is worth noting that many will remember the “Mumbles Railway” today for its electric tramcars, which took over from 1929 until closure in 1960. The evolution of this railway and its willingness to change has been a key characteristic of those early railways that have prevailed in some way; some survive today as heritage enterprises, although sadly the Swansea & Mumbles is not one of them.

Though no longer with us, there are some traces of the S&MR still standing, albeit from later in its history. Mumbles Pier, for example, was built 1897/98 by W Sutcliffe Marsh (engineer) to serve as the southern terminus for the S&MR. Interestingly, the Llanelly Railway obtained permission in 1865 to build a Mumbles branch and pier, but this was never completed. The S&MR pier was authorised by an Act in 1889 and has weathered significant threats over the years – its breaching as an anti-invasion measure during the Second World War being a key one. In 2023/24 it had its substructure lattice replaced with curved plate girders.

A 1927 S&MR electricity sub-station of brown brick with concrete dressings is another survivor, described by the listing authority as “the only substantial remaining structure of the S&MR”. It also served as Blackpill station and can now be found at the Blackpill Lido. Both the pier and sub-station are Grade II-listed.

First sustained commercial steam railway

Middleton Railway (1812)

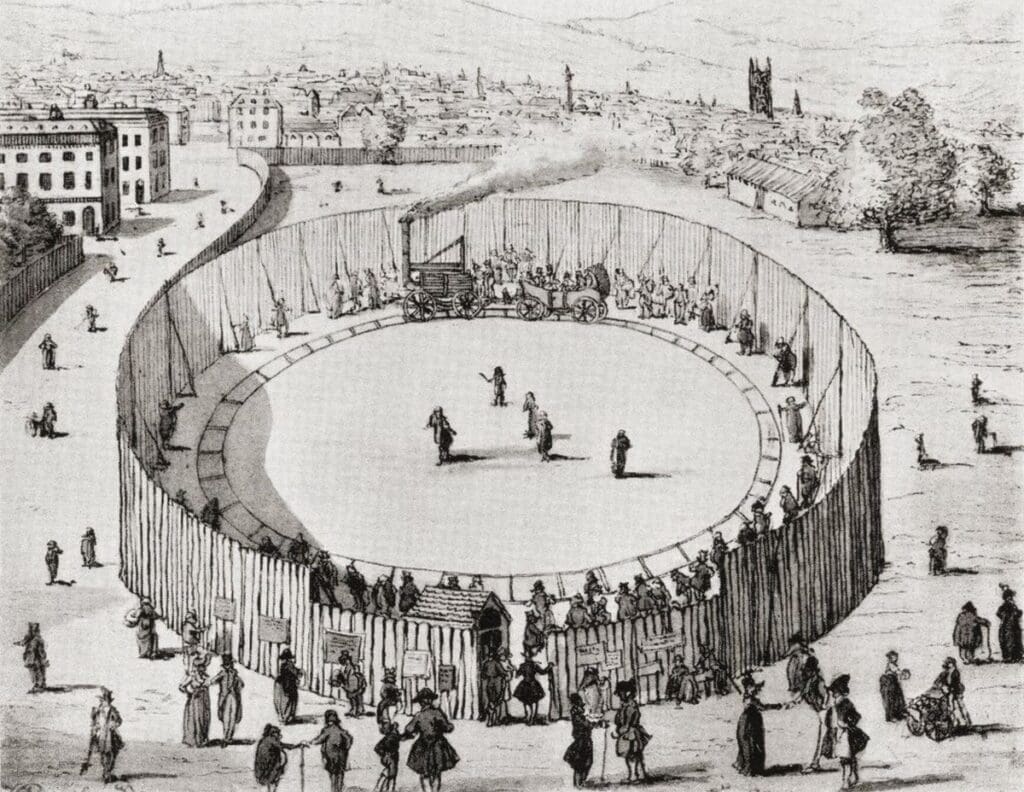

A return to the Middleton Railway for another ‘first’ brings us closer to the winning formula of the S&DR; the MR being regarded as the first to have a sustained commercial steam railway in 1812. Notably, Euston Square is considered the first to use steam locomotives to pull passengers in 1808, though for entertainment purposes only (Richard Trevithick’s ‘Catch Me Who Can’), making the MR the first to make both consistent and commercially successful use of steam locomotives.

It is fitting that our main line tour should be bookended by the MR as, more than any of the others to come before the S&DR, the MR can be said to bear the strongest resemblance to the S&DR and to some other key ‘firsts’ outside of our tour – for example, the MR’s engines.

When thinking of ‘first’ claims, many readers would – quite rightly – have a certain Welshman in mind. Richard Trevithick is credited with giving us the first steam locomotive in 1804 on the Penydarren Tramroad, where bridges of an impressive scale dating from around 1815 remain today spanning the River Taff and listed at Grade II*.

But the MR also had important early engines in the shape of John Blenkinsop’s steam locomotive, introduced in 1812 and operating on a rack and pinion. Blenkinsop’s grave, located at the Church of the Holy Trinity in the Leeds town of Rothwell, is dated 1831 and Grade II-listed. Further lettering was added in the stone in the year of its centenary (January 25, 1931) to tell us more: “John Blenkinsop invented the rack railway in 1811 and on a line he built between Leeds and Middleton, 4 Matthew Murray locomotives ran from 1812 to 1835. His system was adopted at Newcastle-on-Tyne in 1813 and Wigan in 1814 – These railways were the first on which steam locomotion was a commercial success.”

There’s a kind of ‘evolutionary logic’ at work here, which should temper any claim to Stephenson as ‘fathering’ the railways. Indeed, in this author’s view, recognising the early and contemporary contributions of others is fruitful during Railway 200, as it works to bolster Stephenson’s (together with Timothy Hackworth’s) achievements and to understand why the S&DR was configured as it was in 1825.

While Blenkinsop’s rack engines on the MR in Leeds may have been the first practical steam locomotives, it was in the North East of England, on another pre-S&DR railway, that the first all-steam railway was built. Using both locomotive and fixed engines (similar to the S&DR), the Hetton Colliery Railway provided a connection between the colliery (about two miles south of Houghton-le-Spring) and a staithe on the River Wear. This was the first railway to be designed from the start to be operated without animal power, and George Stephenson was behind it. The HCR marked the man’s first entirely new line, bearing some important blueprints for the S&DR that would soon follow.

First-bridges (1727, 1794)

Inspired by the mighty spans of the Penydarren Tramroad, let us take a ‘branch line’ in the story to look at first bridges.

Skerne Bridge on the S&DR enjoyed an upgrade to Grade I protection in 2021, regarded as the oldest railway bridge in the world still in continuous use. But another Grade I railway bridge takes out the ultimate in ‘firsts’ claims. Causey Arch in County Durham, which was a wagonway bridge, dates from around 1727. It was designed by Ralph Wood and is 105 feet long (32 metres) and 80 feet high (24 metres) above a wooded gorge. It is no minor achievement, even today, consisting of a round arch of three courses of voussoirs, the inner recessed, and wide buttresses with Causey Burn running through.

So toweringly elegant an accomplishment that, it is rumoured, the sheer impossibility of such a slender structure staying up drove its designer, a local master mason, to throw himself to his death from it before it was completed. This might sound like a tall tale, though Durham County Council included this incident in its informational materials for the site.

Causey Arch, as with Skerne, was fuelled by the coal industry, being regarded by experts as an example of the early technological skills of the Northumberland and Durham coalfield engineers and the oldest surviving single-arch railway bridge in the world.

Ralph Wood, nor anyone else in the world at the time, had no experience of building such a bridge, so he relied on Roman technology – a principle that proved sound. Two tracks of wood rails crossed the bridge, one to take coal to the River Tyne, the other carrying returning empty wagons. Some 930 horse-drawn wagons crossed it a day in each direction, meaning one wagon every 20 seconds on average. But this schedule would only last a few years and, following closures of nearby pits in the 1730s plus a fire at the Tanfield Colliery in 1740, demand declined until by the 1770s the arch was little used.

Thankfully the structure was saved by restoration work in 1981, caried out by the County Engineer. This work included consolidation of the arch stonework using special resins inserted by a vacuum process and the rock being reinforced with steel rock-bolts.

The arch formed part of the Tanfield Railway (TR), which prevails today as a running heritage railway. And yes, the TR makes a ‘firsts’ claim: “Dating back to 1725, a whole century before the Stockton & Darlington Railway,” its website reads – meaning the railway is having its own celebrations this year of a 300th anniversary, “the first working railway to do so!”

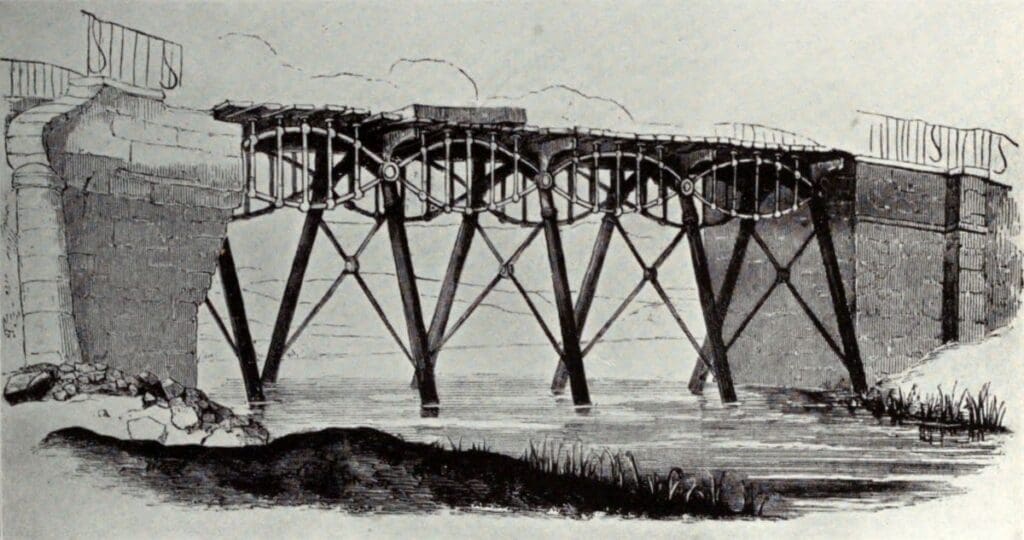

We end our ‘branch line’ to bridges on a point of contestation for some: the world’s first iron railway bridge. George Stephenson’s Gaunless Bridge on the S&DR was completed in 1823 as purportedly the world’s first iron railway bridge. Many sources name it as such, though today experts tend to give this credit to the circa-1794 Pont-y-Cafnau tramway bridge in Merthyr Tydfil, Wales – which is listed at Grade II* and a Scheduled Ancient Monument.

Reminiscent of the pioneering use of iron on other early railways, like Coalbrookdale, this small ironwork bridge spanning the River Taff once served the Cyfarthfa Ironworks immediately to the south, originally carrying a 4-foot gauge tramroad. A pair of A-frames with braces and vertical ‘king-posts’ are supported by coursed rubble abutments.

Prior to Railway 200, the iron span of Gaunless bridge underwent restoration, with research helping a return to it is original green and white livery in 2024. After languishing for some time as an unutilised attraction in a carpark at the National Railway Museum in York, it is now a star object at Locomotion in Shildon. Its abutments remain in situ along the river and have also benefited from S&DR 200th-year appetites for preservation, being awarded grant funding for repair in 2023 by Historic England – and curiously dubbed the ‘World’s First Iron Railway Bridge’ in HE’s news item about the grant. Locomotion calls its new star “the very first railway bridge to use an iron truss.”

We all love a good wrestle for first, it seems. Not a bad thing, really. Something at the heart of early railway enterprise, certainly. And a key means of setting a railway company apart from its competitors. But under these claims, beyond their marketing magic, lies a more meaningful genesis and evolution of the railway idea.

On the shoulders of giants

It is difficult to overstate how visionary Stephenson (and also his contemporary Timothy Hackworth) was on the S&DR. In this author’s view, it is fitting that this year should be celebrated as the bicentenary of the railways. Because although this story focuses on the ‘firsts’ before 1825, there was plenty about the S&DR that was foundational – including some great efficiencies and an overall ethos that would shape the railways to follow. One example is Stephenson’s straightening of the route (with amendments to George Overton’s original 1821 line), favouring gradual inclines and eased curves, to become a characteristic of eminent lines from the ‘golden age’ of railway expansion.

So there is much about the S&DR that served as a blueprint for the modern network. But also, if Stephenson saw further than his contemporaries to what the railways could be, he did so from the shoulders of many greats who rose and worked with him, and a good many who had come before.

Our titans of Britain’s industrial age have a certain (some might argue deserved or hard-earned) reputation for protective pridefulness in their innovations and unique abilities. I am thinking of Thomas Telford’s actions in the first round of proposals for the Clifton Suspension bridge, the project later awarded to Brunel; or Robert Stephenson’s (George’s son) insistence on taking full credit for the tubular concept in bridge design at Conwy and across the Menai Straits (a concept that changed the world).

But with all due respect, the engineers and the individual railway enterprises remembered now as giants of their age owe a not-inconsiderable portion of their triumphs to having ideas – sound, strong and fantastically novel in important respects – that nonetheless built on the pioneering efforts of the various ‘firsts’ of many kinds that pre-date ‘200 years of the railways’ as we know them today (that last part being an important qualifier).

In short, all of us who celebrate this year as the birth of the railways as we now know them, would do well remembering too the longer, more nuanced history of our iron roads.