The German capital boasts some fascinating railway architecture, from timbered cottages to cathedral-style underground stations and ultra-modern designs. Chris Milner paid a visit to seek them out.

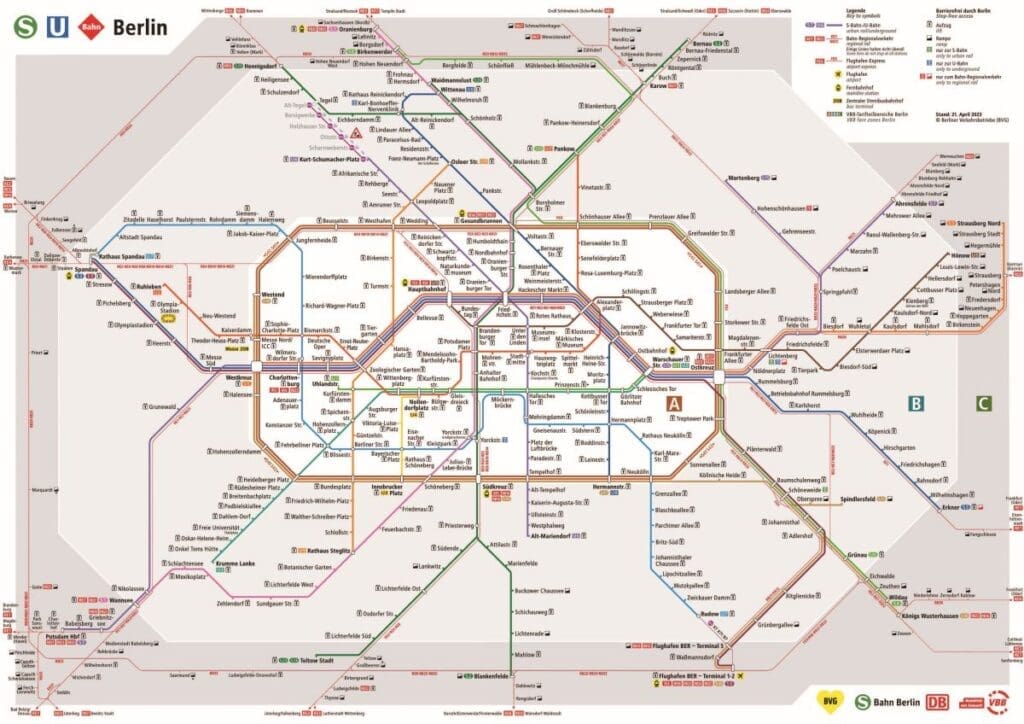

Home to almost 3.6 million people, Berlin has expanded and modernised considerably since reunification in 1990. For its residents, the city’s impressive public transport system – covering rail, tram, ferries and bus – is the backbone of the day-to-day, with a comprehensive and interconnecting system operated by BVG (Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe) which was founded in 1928. The BVG network is extensive and there are many places where the S or U-Bahn connects to DB network services.

At the end of the Second World War, Berlin was split into four sectors divided between the British, American, French and Soviets – but it was the construction of the infamous Berlin Wall, completed in August 1961, that segregated around one million people in East Berlin (and what was then East Germany) under the control of the German Democratic Republic allied to the Soviet regime. Much of the city’s historical and cultural sector was in the East, and much of today’s tram network was also originally in the former East.

Its wider railway history is particularly fascinating and, while outside of the scope for this article, is worthy of deeper investigation, as there have been so many changes since the end of the Second World War. These changes are still happening too. In December 2020, a new 2.2km link between Brandenburger Tor and Alexanderplatz opened, creating a through route from Hönow in the east to Berlin Hauptbahnhof, the city’s main station.

Hauptbahnhof is an impressive modern glass, steel and concrete design, with trains running on both north-south and east-west axes, built on the site of Lehrter Bahnhof with construction beginning properly in 1995 and completion not achieved until 2006.

A city divided

The building of the Berlin Wall in 1961, which was 140km long, had a big impact on rail routes. Some routes, such as U-Bahn line U1, were forced to terminate at Schlesisches Tor because the end of the line at Warschauer Strasse – across the beautiful Oberbaumbrücke spanning the River Spree – was in East Germany. As a divided city, there were specific checkpoints for residents to pass from one sector to another.

On several U-Bahn lines, trains ran through stations in the East without stopping. At these ‘ghost’ stations, armed guards were stationed on dimly lit platforms to stop escapees boarding should the train unexpectedly stop. The guards were also present to prevent East German residents escaping using the rail tunnels. To aid them, the Communist regime used alarm-linked pressure-sensitive trip switches and even steel grilles to block lines at night, to prevent people escaping from East to West.

At large interchange stations such as Friedrichstrasse, which had checkpoints for passengers’ documents to be checked, the network of pedestrian tunnels was laid out in such a way to ensure passengers from the Democratic and Federal Republics remained segregated. Today, Nordbahnhof station hosts a permanent exhibition reflecting that era of the ghost stations.

By the summer of 1990, with the wall down and Germany beginning the long process of reunification, the ghost stations reopened, the first being Jannowitzbrücke on November 11, 1989. However, with changes to station walkways and the passage of time, it is almost impossible today to determine where passenger segregation took place.

The opening of the first line on the U-Bahn (the Berliner Hoch und Untergrundbahn – Berlin Elevated and Underground Railway) was built by Siemens & Halske and opened in 1902. The inaugural route was an elevated line on an east-west axis from Warschauer Strasse towards Nollendorfplatz. It remains one of the most interesting sections of a U-Bahn journey.

Planning a visit

Several previous visits to Berlin for the biennial ‘Innotrans’ railway trade show had always been short in duration. Having first visited Berlin briefly in 1992, and again in 2005, a 2016 visit was accomplished as a day trip, home to Berlin and back in 22 hours – ridiculous in hindsight. Returning again in 2018, I stayed for a couple of nights, which was less frantic but still did not really allow sufficient time to see some of Berlin’s more fascinating railway stations featuring some very interesting railway architecture. With Innotrans cancelled in 2020 because of Covid-19, for 2022 I made plans for a four night/five day stay that also provided plenty of time to travel on a comprehensive network of lines and see more of the city.

Aware of some locations from past visits, I researched all other 175 U-Bahn and 168 S-Bahn stations using a couple of books – Capital Transport’s Berlin S-Bahn and Robert Schwandl’s excellent bi-lingual publication U-Bahn, S-Bahn & Tram in Berlin. I also found Wikipedia and other websites had pictures of most of the stations.

With a network length of 155km, U-Bahn stations are of varying style or design, many of those underground having different tiling – some coloured, some patterned. Some stations retain vintage lighting, but overall the stations have immense character. The stations of line S1 between Schöneberg and Wannsee are particularly diverse in their architecture.

Some 70 of the U-Bahn stations were designed by Swedish architect Alfred Grenander, his first designs being Art Nouveau or Neo-Classical before adopting a modern style. His notable designs include the cavernous Hermannplatz, Wittenbergplatz, Olympia-Stadion (built ahead of the cancelled 1916 Olympic Games) and Krumme Lanke, which is said to have inspired Charles Holden for his London Underground station designs.

The S-Bahn covers a wider area (a 339km network) and has evolved with fast and frequent cross-city services. Although many stations are modern, or have been rebuilt to cater for expanding population in certain areas, there are plenty that retain much of their original charm and character, having ornate canopies or buildings clad with ceramic tiles.

What is clear is how each station has a key place in the community it serves. Many have a cafe or bar attached where locals will socialise. Some had convenience stores integral to the design and a large number have flower shops.

Maps and tickets

Having shortlisted which stations to visit, marked on the BVG network map, I used then Google maps to look at the location of each station, checking both the external and satellite views. Then, using the free app ‘maps.me’, I activated a public transport layer that showed the proximity of one station to another. This revealed some stations were far closer in reality than the schematic map – a 10-minute walk in one instance, saving a lengthy doubling back. I also used the BVG tram and bus maps to find other useful cross-city connections.

With the plan refined, I used the BVG app (or website) to establish station-to-station journey times, primarily to check if my plan was achievable or over ambitious. While there was some modification for one day, that was only a result of having aching feet due to a poor sock/shoe combination! So do wear comfortable footwear, as at the end of my trip I had walked a few steps short of 70,000 – equivalent to 29.6 miles!

As regards travel tickets, a trade pass for Innotrans provides free travel in Berlin zones ABC, but tourists can use a 24-hour travelcard/pass for €10.70, a bargain considering the standard single journey ticket is €2.20 or 3.20, depending on distance.

With no ticket gates to battle with, you can just wander on to platforms, which is perfect for a rail enthusiast. But be warned, there are on-train ticket checks by plain-clothed BVG officials, and if caught with no ticket, a hefty €60 fine is levied.

In respect of traction, Berlin’s U-Bahn still uses many of the characteristic F-type trains dating from the 1970s, supplemented by newer G, H, HK and IK units. The S-Bahn uses a mix of Class 481/482 stock dating from 1995, new Class 483/484 and a small number of Class 480/485 built in the 1980s.

Much to see and do

As a vibrant cosmopolitan city, there were no concerns over personal safety, but you should always be alert. Neither were there any issues whatsoever taking pictures at stations, including underground – although use a high ISO where necessary and not a flash. There are plenty of places to eat and drink too as you move around the city.

The city’s railways play an important part of Berlin’s rich history and connect to the famous tourist sites, such as the Reichstag, Brandenburg Gate, Deutsches Technikmuseum, the Fernsehturm (TV tower), Checkpoint Charlie, the Jewish Museum and Rotes Rathaus. The extensive S-Bahn and regional DB services also connect the city centre with Berlin Brandenburg airport and further afield.

There are some gems too. South-east of Berlin on S-Bahn line S3 is Rahnsdorf (40mins from Alexanderplatz), where across the road from the station is tram line 87 that runs through an attractive suburb to Woltersdorf. The line, which is 110 years old, still uses 60-year-old twin-axle Gotha trams – but not for much longer, as new modern trams are on order. The ride is included with the all-zones pass too.

The city does have a U-Bahn Museum near the Olympia-Stadion station, which is temporarily closed as a result of the pandemic, while a new S-Bahn museum at Lichtenberg station is under construction and scheduled to open in August 2024.

Berlin is a tremendous city to visit for a short break, easy to get around, with accommodation choices to suit all pockets and so much of interest for all tastes. Something to consider for the late summer or autumn?