We have received payment for the content in this article. Learn more.

The Coming of the Railway is the first global history of the epic early days of the iron railway. Railways, in simple wooden or stone form, have existed since prehistory. But from the 1750s onward the introduction of iron rails led to a dramatic technological evolution – one that would truly change the world. In this extract, author David Gwyn introduces the neglected story of the early iron railway.

My new book, The Coming of the Railway, is a history of the early iron railway: an account of how a means of transport running on iron rails and using mechanical traction came into being in the second half of the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth, how it evolved from the earlier forms of railway which were operating in Britain, how it then went through a particularly rapid period of transformation between 1786 and 1830, and how over the next 20 years it became a widely accepted means of moving people and goods over much of Europe and North America.

This is not an inquiry into the origins of the railway. Rather, I set out to explore a crucial period of its history, to see how it met the needs of the Industrial Revolution, that profound change in human circumstances which involved not only new methods of manufacture but also more effective means of distribution. The fundamental concept of the railway, a prepared way that both guides and supports wheeled vehicles, dates from prehistory. By the eighteenth century, railways were already a well-established technology. Practically all were mineral-handling systems. They could be found as far east as Kazakhstan, and as far west as France and Ireland. They were constructed almost entirely of wood, and relied on the power of humans, horses or oxen for propulsion. Most operated in darkness underground, though some might extend from the mouth of a mine level for a short distance to a dump or a crushing plant. Only in some British coalfields were there any railways longer than a few hundred yards. In the north-east of England it was agreed that one of these wooden ‘waggonways’ could be cost-effective up to 10 miles in length, from the pit-head to staithes on the Tyne or Wear rivers. An increase in the demand for coal made it clear that this was a technology with great potential for adaptation and development which could benefit many other industries and economies.

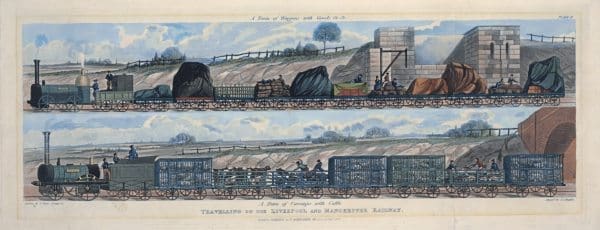

As a result, railways came to carry not only minerals but also foodstuffs and goods such as cotton, a staple of the emerging global financial system, as well as offering passenger services. Most notable in this respect was the Liverpool and Manchester, opened in 1830, which was the first to connect two great trading cities.

Railways also came to be built in places where they had never existed before, and on a vastly greater scale. In 1832 the first railway connecting two great continental rivers was finally completed, between Budweis and Linz in the Austrian Empire. The following year the first railway over 100 miles in length was put into service, the Charleston and Hamburg in South Carolina.

These changes were made possible by a culture of experimentation and of constant adaptation, and by a growing understanding of new materials, specifically the progressive substitution of iron for wooden elements. The inclined plane was patented in Britain in 1750. Significant use of iron began in 1767, when cast-iron straps on wooden rails are first recorded. In 1786–7 the first all-iron rails were introduced. Within a few years, there was the additional option of using mechanical traction powered by fossil fuel in the form of fixed high-pressure steam engines which wound haulage ropes, or even self-propelling ‘locomotive engines’. These became a possibility in the context of the coal and metallurgical industries of England and Wales, but soon spread to other countries, revolutionised in 1829–30 by Robert Stephenson’s Rocket/Northumbrian/‘Planet’/‘Samson’ design. It soon became clear that a locomotive and its train running along iron rails could accomplish what the carrier’s cart, the stagecoach and the canal barge could not.

Historians have often referred to the years from 1825 to 1830 as the dawn of a ‘railway age’, but the evolution of railways over the previous 80 years or so remains much less known, despite many excellent specialist histories. There is little collective understanding of their own very considerable economic impact. A French visitor to Newcastle in 1765 could see that the phenomenal growth of the coalfield was due to its wooden waggonways to the Tyne. A short hand-propelled system, running on cast-iron rails a few yards from a canal wharf to an adjacent limekiln, or moving manure in a farmyard, also reduced transport costs significantly. These systems are as much part of the story as the steam networks which evolved from them, but history books have little to say about the changes which led from one to the other, and how the achievements of celebrated engineers such as the Stephensons were based on experience gained earlier.

Technical changes take place as components within an engineered system appear, mature, become obsolete and are replaced. In the course of the nineteenth century, wooden vessels moved by wind gave way to iron steamships; rural watermills were superseded by factories where cereal crops were crushed by mechanically driven rollers. Similarly, the railway underwent an evolutionary change common in the Industrial Revolution, by progressively replacing organic elements activated by natural forces with mechanical technologies made of iron and powered by fossil fuels. Technical changes also relied on improved capacity and on a better understanding of physical phenomena, whether established by rational enquiry or by trial and error. In this respect, the early iron railway could be compared with the electric telegraph, which developed within almost exactly the same time frame.