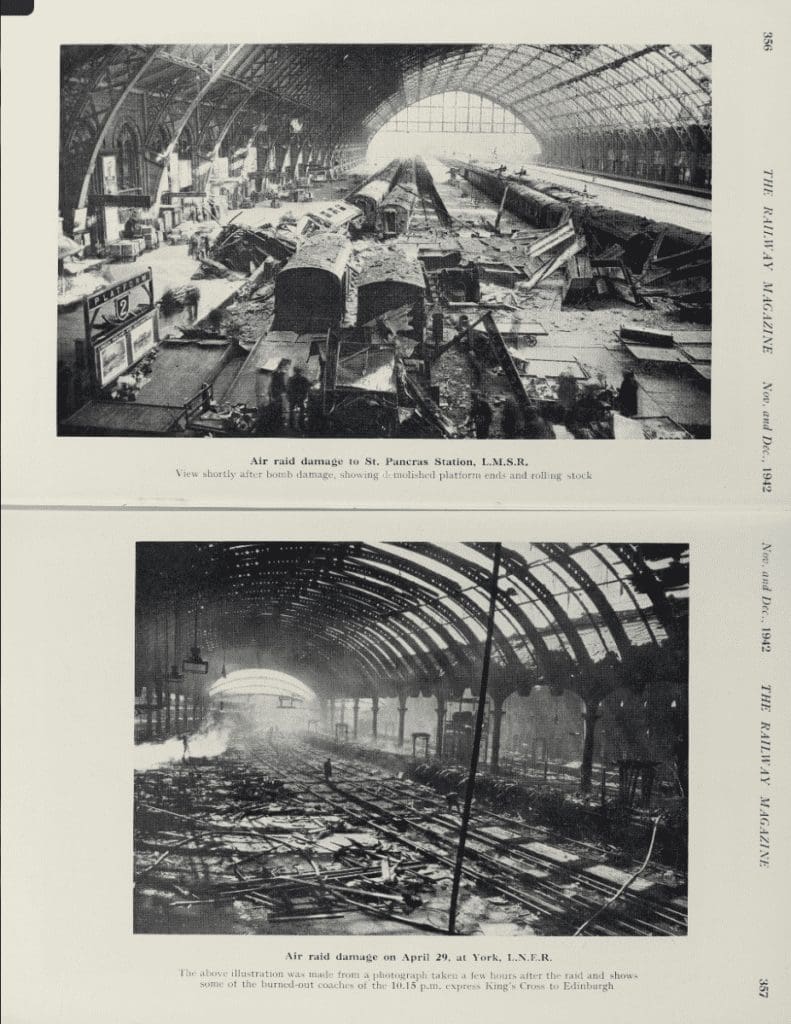

These images from the November/December 1942 edition reveal bomb damage in London and York

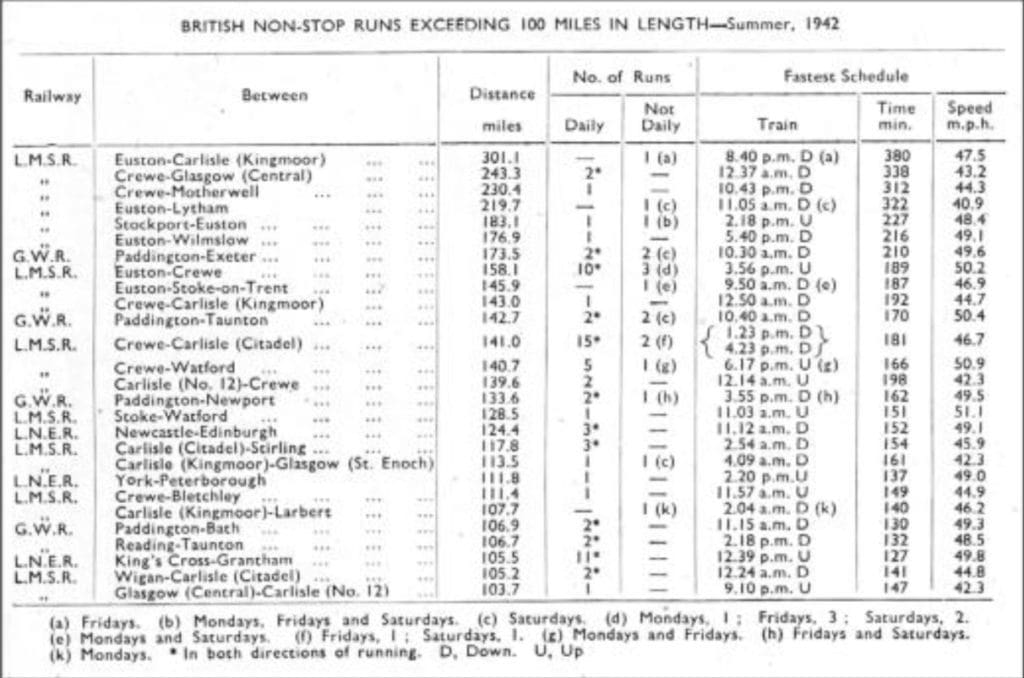

British non-stop runs in Wartime

By “Mercury”, from the September/October 1942 edition of The Railway Magazine.

CERTAIN features of the British 1942 summer train services, after nearly three years of war, are remarkable and in particular the number and length of non-stop runs scheduled in the timetables.

The L.M.S.R. has recognised the fact that where station stops are not essential, and trains can command through passenger complements over long distances, much delay by passenger occupation of running lines is avoided if such trains are kept on the move.

Severe congestion at Carlisle in particular, during the night hours, is eased by running northbound trains through the station to Kingmoor for examination and engine-changing, and by similarly dealing with certain up trains at Carlisle No. 12 instead of in the passenger station; in addition there are the two notable runs of the Night Scot in each direction over the 243.3 miles between Crewe and Glasgow (Central) – easily the longest daily non-stop runs in the world with steam power – and the 230.4 miles of the wartime version of the Royal Highlander from Crewe to Motherwell.

Beating even these is the 8.40 p.m. Glasgow express from -Euston on Friday nights, which is booked over the 301.1 miles to Kingmoor without a stop – an astonishing wartime feat.

Also, following the Night Scot, there is the 9.20 p.m. from Euston, which runs non-stop from Crewe to Kingmoor, and then non-stop from Kingmoor over the Glasgow & South Western section to the St. Enoch station at Glasgow, 113.5 miles, with the help of Floriston and New Cumnock water-troughs. Other interesting novelties are a daily run over the 183.1 miles from Stockport to Euston, and one on Saturday mornings over the 219.7 miles from Euston to Lytham. The G.W.R. record is still held by the Cornish Riviera Limited, with non-stop runs in each direction over the 173.5 miles between Paddington and Exeter (with two additional down runs on Saturdays); the L.N.E.R. has nothing longer to show than the 124.4 miles between Newcastle and Edinburgh.

In all, there are’ now 72 daily runs over 100 miles in length, and 40 of these are over 140 miles; 47 of the former and 36 of the latter are made by the L.M.S.R. The L.N.E.R. is responsible for 15 daily 100-mile runs and the G.W.R. for 10.

That such a list can be scheduled in present conditions is a tribute alike to the standard of locomotive maintenance and to the efficiency of British railway operation in wartime.

Fuel difficulties in Eire

THE fuel difficulties of Eire in present war conditions are common knowledge, but the effect on locomotive working of the type of fuel in use may not be so readily understood. We have recently received an interesting letter on the subject from Mr. H. Turpin; it describes how the slack coal, or “duff” as it is called, is so finely divided that if it is raked thoroughly to obtain a draught it simply drops through between the bars, and the firebox thus empties itself. In consequence, the slack has to be packed in a solid mass in the firegrate, through which no draught can penetrate, and though an engine may accumulate full boiler pressure after standing in a station, in a matter of a few miles the pressure has dropped to such an extent that the train stalls. An outcome of this is that double-heading and triple-heading, even with the most powerful locomotives, are common. On a recent occasion, when our correspondent observed the 9 a.m. from Dublin to Cork at Maryborough, it had contrived to cover no more than this 51 miles in just over 4 hr., with 3—cylinder 4-6-0 No. 800, Maeve, piloted by one of the oldest Aspinall 4-4-0s, and after it had stood there 15 min. a rebuilt 4-4-0 was attached in front, the whole cavalcade leaving 1 3/4 hr. late at the end of a 20 min. stop. On another occasion the same train reached Maryboroug with rebuilt 4-4-0s No. 330 and 314, and went out with 0-6-0 No. 186 as second pilot; on a third occasion the triple power was nicely graded with a 0-6-0 in front, a rebuilt 4-4-0 in the middle, and the 4-6-0 Maeve as the train engine. Incidentally, Great Southern locomotives are having their number-plates removed and painted numbers substituted, doubtless with a view to economy in the use of brass.

For more from The Railway Magazine Archive, click here.