Read this fascinating archive article on the Stockton and Darlington Railway, with words and photography as originally printed in the July 1925 issue of The Railway Magazine.

ALTHOUGH not the first public railway in the British Isles (and therefore in the world), in that, besides industrial (mainly Colliery) lines in various parts of the country, some 20 railway Acts had been passed – the most important being that for the construction of the Surrey Iron Railway authorised in 1801 – the Stockton and Darlington was the first public railway on which locomotive traction was employed and intended to carry both passenger and goods traffic on lines suggestive of modern railway methods. As pointed out in an article published in the Railway News in 1866, the necessity for improved means of transporting heavy loads at a cheap rate being more urgently felt in the coal districts of the north than anywhere else, it was perhaps natural that the first successful attempt to establish a public railway should have been made in that quarter; and for the reason that many of the first railways originated in the coal areas, so were they the scene of action of the first successful railway locomotives.

Some of the richest coalfields of Durham and Northumberland lie well inland, comparatively distant from the sea, and the shipping places on the Tyne, the Wear and the Tees. It was, therefore, with difficulty that the coal could be got to market, and until that could be accomplished, the coalfields, no matter how productive, were comparatively valueless. One of the richest of these coalfields, lying to the west and north-west of Darlington, is well known as the Bishop Auckland district. It lay a long way from the sea, and, the Tees being unnavigable, there was next to no vent for the Bishop Auckland coal. We can easily understand, therefore, how the desire of obtaining an outlet for this coal for land sale as well as for transport to London by sea, should have early occupied the attention of the coalowners in the Bishop Auckland district.

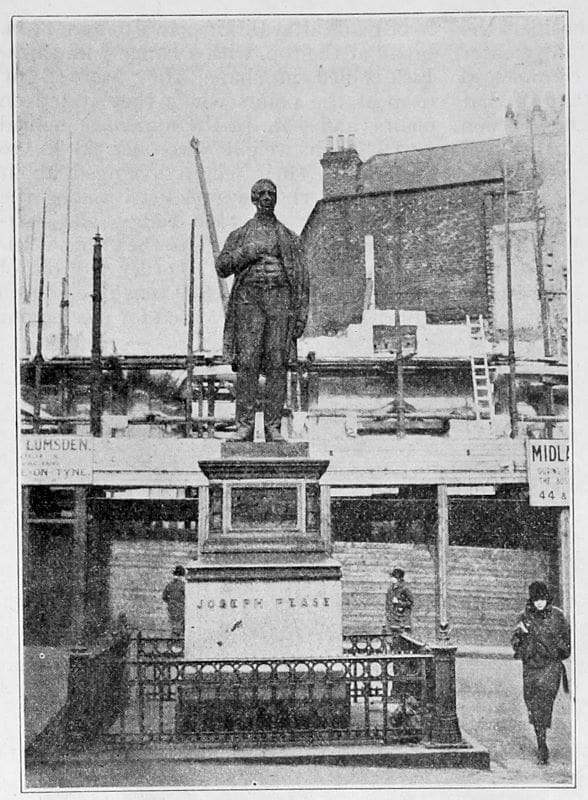

Among Various pre-railway proposals was one for a canal to connect the Darlington district with Stockton-on-Tees, and it is of interest to note that John Pease, a member of the family which became so prominently associated with the Stockton and Darlington and North Eastern Railways, was one of the Darlington Committee appointed to consider the proposal. George Dixon, grandfather of John Dixon, who also became associated with the Stockton and Darlington Railway, was concerned in the surveys, on the basis of which plans were eventually prepared for a canal from Stockton via Darlington to Winston. As the Railway News puts it, however, nothing was done, and enterprise was slow to move. “Stockton waited for Darlington, and Darlington waited for Stockton”: but neither stirred, until twenty years later, when Stockton began to consider the propriety of straightening the Tees below that town, and thereby shortening and improving the navigation.

Several other canal schemes were then mooted, but apparently the only result, so far as water transport is concerned, was the obtaining by the Tees Navigation Company, in 1808, of an Act enabling them to make the short cut projected seventeen years before, and thus to improve water access to the coal area. This improvement was completed in 1810, when another committee was appointed to consider again proposals for a canal from Stockton via Darlington to Winston, with the alternative suggestion of a railway, a main object being to still further improve access to the colliery districts concerned with a view to making the new cut a success.

Nothing, however, was done by the Stockton Committee, and sixteen months later the matter was revived at Darlington with Edward Pease as one of the members. To advise them as to the respective merits of rail and canal, John Rennie was asked to report. This report was presented in 1813, but was not apparently published. As far as can be gathered, however, he favoured a canal, though he afterwards inclined toward a tramroad. Once again, nothing definite followed, and in 1818 further proposals were advanced from Stockton for a canal, these being associated with the names of Edward, John and Thomas Pease and John Dixon. As a result, it was decided to apply to Parliament for an Act to make the intended canal “if funds are forthcoming.” As the money was not, apparently, forthcoming, the Stockton people were not able to make further headway, but in September, 1818, the Darlington people again took action. Mr. Rennie was consulted afresh, in conjunction with a Mr. Overton, who had been concerned with several coal railways in Wales. A railway was suggested via Darlington in preference to a canal via Auckland, whether taken as a line for the exportation of coal or as one for a local trade.” The report concluded as follows:

“As a whole, the committee recommend the constructing a rail or tramroad throughout the entire line presented between Stockton, Darlington, and the collieries.”

A survey for the proposed railway was made and steps taken to apply to Parliament for the necessary powers. The Stockton people, however, still favoured a canal, though apparently they were not prepared to subscribe thereto, or, indeed, to the alternative railway, and, as a result, the railway project was pushed almost exclusively by the Darlington people. The scheme was, moreover, fiercely opposed in three successive sessions of Parliament. The application of 1818 was defeated by the Duke of Cleveland, who afterwards profited so largely by the construction of the railway. The ground of his opposition was that the line would interfere with one of his fox covers, and through his influence the Bill was thrown out.

The next year, in 1819, an amended survey of the line was made; and, the Duke of Cleveland’s fox cover being avoided, his opposition was thus averted. But as Parliament was dissolved on the death of George III, the Bill was necessarily suspended until another session. The principal opposition now came from the road trustees, who spread it abroad that the mortgagees of the tolls arising from the turnpike road leading from Darlington to West Auckland would be seriously injured by the formation of the proposed railway. On this, Edward Pease issued a printed notice requesting any alarmed mortgagees to apply to Mr. Raisbeck or Mr. Mewburn, the company’s solicitors at Darlington, who were authorised to purchase their securities at the price originally given for them. This notice had the effect of allaying the alarm, and the Bill, though still strongly opposed, was allowed to pass both Houses of Parliament in 1821.

The preamble of the Act set forth the public utility of the proposed line for the conveyance of coal and other commodities from the interior of the county of Durham to Stockton and the northern parts of Yorkshire. Nothing was said about passengers, for passenger traffic was not then contemplated; and nothing was said about locomotives, as it was at first intended to work the line entirely by horse—power. The road was to be free to all who chose to place their wagons and horses upon it for the haulage of coal and other merchandise, provided they paid the tolls fixed by the Act.

The company were empowered to charge 4d. a ton per mile for all coal intended for land sale ; but only 1/2d. a ton per mile for coal intended for shipment at Stockton. The latter low rate was introduced in the Act through the influence of Mr. Lambton, afterwards Earl of Durham, for the express purpose of preventing the line being used in competition against him; for it was not believed possible that coal could be carried at that rate except at a heavy loss. As it was, the low rate thus fixed proved the vital element in the future success of the Stockton and Darlington Railway.

Apparently, Edward Pease and those associated with the scheme had little or no idea of using locomotive engines. After the Act had been obtained, however, George Stephenson having been appointed engineer to lay out the line and to superintend its construction, Edward Pease seems to have come to believe in the possibilities of locomotive traction, and though the directors generally were in favour of horse haulage, the influence of Mr. Pease at the board was such as enabled him to obtain a fair trial for the engines that Stephenson advocated with such unhesitating confidence, and three locomotives were accordingly ordered to be constructed and delivered in time for the opening of the railway. The first was delivered in September, 1825, and the two others a week later, when they were immediately set to work to draw the coal wagons.

Three years were occupied in construction, and on September 27, 1825, “a great day for Darlington,” the line was publicly opened. Opinions were pretty equally divided as to the railway, but as regarded the locomotive the general belief was that it would “never answer.” However, there the locomotive was – “ No. 1 ” – delivered on to the line, and ready to draw the first train of wagons on the opening day. The proceedings were thus described by the Railway News of the period :-

A great concourse of people assembled on the occasion. Some came from Newcastle and Durham, many from the Aucklands, while Darlington held a general holiday and turned out all its population. To give éclat to the opening, the directors of the company issued a programme of the proceedings, intimating the times at which the procession of wagons would pass certain points along the line. The proprietors assembled as early as six in the morning at the Brusselton fixed engine, where the working of the inclined planes was successfully rehearsed. A train of wagons laden with coals and merchandise was drawn up the western incline by the fixed engine, a length of 1,960 yards, in seven and a half minutes, and then lowered down the incline on the eastern side of the hill, 880 yards, in five minutes.

At the foot of the incline the procession of vehicles was formed, consisting of the locomotive engine, No. 1, driven by George Stephenson himself; after it six wagons loaded with coal and flour, then a covered coach containing directors and proprietors; next, 21 coal wagons fitted up for passengers (with which they were crammed), and, lastly, six more wagons loaded with coals.

Strange to say, a man on a horse, carrying a flag, with the motto of the company inscribed on it, Pericnlum privatum utilitas publica, headed the procession! A lithographic view of the great event, published shortly after, duly exhibits the horseman and his flag. It was not thought so dangerous a place after all. The locomotive was only supposed to be able to go at the rate of from four to six miles an hour, and an ordinary horse could easily keep ahead of that.

Off started the procession, with the horseman at its head. A great concourse of people stood along the line. Many of them tried to accompany it by running, and some gentlemen on horseback galloped across the fields to keep up with the engine. The railway descending with a gentle incline towards Darlington, the rate of speed was consequently variable. At a favourable part of the road Stephenson determined to try the speed of the engine, and he called upon the horseman with the flag to get out of the way! Most probably, deeming it unnecessary to carry his Periculum privatum farther, the horseman turned aside, and Stephenson “put on the steam.” The speed was at once raised to 12 miles an hour, and at a favourable part of the road to 15. The runners on foot, the gentlemen on horseback, and the horseman with the flag were, consequently, soon left far behind. When the train reached Darlington it was found that 450 passengers occupied the wagons, and that the load of men, coals, and merchandise amounted to about 90 tons.

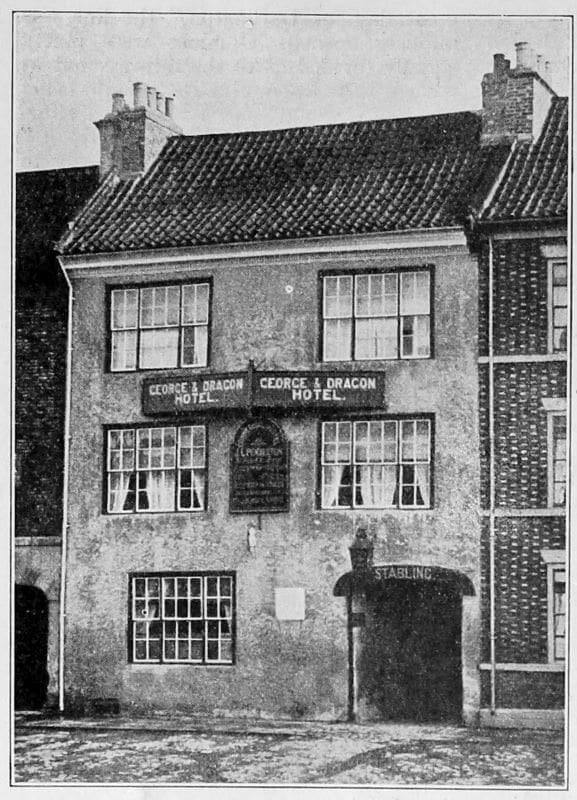

At Darlington the procession was re-arranged. The six loaded coal wagons were left behind, and other wagons were taken on with 150 more passengers, together with a band of music. The train then started for Stockton, a distance of only 12 miles, which was reached in about three hours. The day was kept throughout the district as a holiday; and horses, gigs, carts and other vehicles, filled with people, stood along the railway, as well as crowds of persons on foot, waiting to see the train pass. The whole population of Stockton turned out to receive the procession, and, after a walk through the streets, the inevitable dinner in the town hall wound up the day’s proceedings.

But although the Stockton and Darlington was now launched as an operating concern, it had to justify its construction and cost, with the added burden that, as shown by subsequent history, upon its success or otherwise depended, in large measure, the development or abandonment of rail traction. We may quote a few further extracts from the Railway News for October 6, 1868.

The circumstances were on the whole favourable, and boded success rather than failure. Prudent, careful, thoughtful men were at the head of the concern, interested in seeing it managed economically and efficiently; and they had the advantage of the assistance of an engineer possessed of large resources of mother wit, mechanical genius, and strong common sense. There was an almost unlimited traffic in coal to be carried, the principal difficulty being in accommodating it satisfactorily. Yet it was only after the line had been at work for some time that the extensive character of the coal traffic began to be appreciated. At first it was supposed that the chief trade would be in coal for land sale. It was estimated that only about 10,000 tons a year would be shipped, and that principally by way of ballast; instead of which, in the course of a very few years, the coal carried on the line for export constituted the main bulk of the traffic, whilst that carried for land sale was merely subsidiary.

It was also pointed out that, although the Corporation of the borough of Stockton welcomed the railway to their port, they were not prepared to provide the additional accommodation required, so that the Stockton and Darlington Company had to incur a great deal of expense which might legitimately have been regarded as an obligation upon Stockton itself. Some of the directors proceeded to purchase the site of a new shipping place on the Tees, a few miles below Stockton, where they erected staiths and provided other conveniences for the speedy loading of coal. This site consisted of about 500 acres of land, the only building standing on it at the time being an isolated farmhouse. All round it were green fields, and along the river mud banks. Before long buildings were erected, and the town of Middlesbrough came into being, thus proving the truth of what Edward Pease had so often predicted, that “If they will only let us make the railroads, the railroads will make the country.”

The original estimate assumed that 165,488 tons of coal would be carried annually, and produce an income of £11,904. The revenue from other sources was taken at £4,104. In 1827, the first year in which the coal and merchandise traffic was fully worked, the revenue from coal was £14,455; from lime, merchandise and sundries, £3,285; and from passengers (which had not been taken into account), £563. In 1860, when the original line of 25 miles had become extended to 125 miles, and the original capital of £150,000 had swelled to £3,800,000, the quantity of coal carried had increased to 2,045,596 tons in the year, besides 1,484,409 tons of ironstone and other minerals, producing a revenue of £280,375; while 1,484,409 tons of merchandise had been carried in the same year, producing £63,478; and 687,728 passengers, producing £45,398.

In regard to public passenger traffic, the first carried on any railway, the Railway News of 1866 pointed out that, although only 40 years had passed, “the original style of travelling by coach on the Stockton and Darlington has already become antiquarian in its character, and it is, indeed, one of the very few bits of antiquity that railways have to boast of.” When the railway was nearly ready for opening, the running of a stage coach on the line was thought worthy of a trial, and a coach was ordered to be made called “The Experiment.” This vehicle was further described as follows :—

This coach very much resembled a showman’s caravan, with three small windows on each side, seated all round, and a long deal table in the middle. The entrance to the caravan was by a door at the back end. It was drawn by one horse, which made the journey of 12 miles between the two towns in about two hours. There was only one class of passengers, and the fare charged was 1s.

This description does not appear entirely to accord with information given elsewhere, in that, while some accounts contributor, others suggest that “The Experiment” was more of a stage coach, with a central closed compartment and open compartments at each end. Subsequent remarks suggest the probable explanation, as shown by the following extract :—

“The Experiment” filled very well – so well that it sometimes could not contain half the passengers who presented themselves. When it was heavily laden, the one horse could with difficulty draw it, especially on the return journey from Stockton to Darlington, where the gradient was all up-hill. It was accordingly determined to banish the lumbering caravan to the coal districts of the west, and to employ a new kind of vehicle for the better accommodation of the traffic between Stockton and Darlington. A number of old stage coach bodies were bought and mounted on underframes with flange wheels. These coaches were let to contractors who horsed and worked them, paying certain agreed tolls to the company. The outside fares were 1s. for the 12 miles, and the inside fares 2s. From 15 to 20 persons could contrive to seat themselves outside, the inside passengers being limited to six.

Further quotations bring out certain other aspects which appear to be worthy of record, as follows :—

The speed of the new coaches was raised to about 10 miles an hour; and two journeys were made daily between Darlington and Stockton and back. When the coach drew near to any bend of the road at which the view was obstructed, the coachman blew a horn to give warning of his approach to the drivers of any wagons coming from the opposite direction. The road being as yet only single, there were passing places provided, into which the coming vehicles were drawn to enable the proceeding coach readily to pass. Sometimes it happened that the coaches met on the single line between two passings, and then an altercation would arise between the drivers as to which should turn back. When an agreement was come to, one of the coachmen unyoked his horse, reyoked him to the opposite end, and drew the vehicle back to the next passing place, to allow the other to proceed.

A writer in the Caledonian Mercury of the time described in glowing terms the wonders of this new mode of conveyance. “Nothing appeared more surprising,’ observed the writer, “than the rapidity and smoothness of the motion, considering that the coach had no springs, and also the ease with which the animal drew his load. We left Darlington with 13 outside passengers, and two or three inside, and picked up various others on the way. In regard to passengers, the coach appears to be no way limited in its numbers. The coachman informed us that one day lately, during the time of the Stockton races, he took up from Stockton 9 inside and 37 outside, in all 46. Of these some were seated all round the top of the coach on the outside, others stood crowded together in a maze at the top, and the remainder clung to any part where they could get a footing. On that occasion he had two horses. Such is the first attempt to establish the use of railways for the general purposes of travelling, and such is the success with which it has been attended that the traffic in this way is already great; and, considering that there was formerly no coach at all on either of the roads along which the railway runs parallel, it is really quite wonderful; its trade and intercourse has arisen out of nothing – nobody knows how. It was unlooked for even by the promoters of the railway themselves, who now draw at the rate of £400 to £500 a year from the coaches alone; and, altogether, the circumstances of bustle and activity which now appear along the line, with the crowds of passengers going and returning, form a matter of surprise to the whole neighbourhood as well as to the public.”

As traffic increased it became necessary for the company to take over its own passenger traffic, and for a period mixed goods and passenger trains were run, until the time came when passenger and goods traffic were separated and locomotive engines used for both, although this was not until some years after the railway had been opened.

It is now necessary to consider the construction of the railway in greater detail. Work was actually commenced on May 13, 1822, and on the 23rd of that month the first rail was laid. The occasion was celebrated by festivities of the kind which appear to have been inseparable from every event of public note in those days. The point where the first rail was laid appears to have been close to St. John’s Well, in Stockton. Construction advanced during 1823, work proceeding for the most part fairly smoothly, though in places difficulties were experienced. Thus, at a place called Myers Flat, between Darlington and Heighington, marshy ground caused trouble not unlike that which George Stephenson had to overcome on a larger scale at Chat Moss when he was constructing the Manchester and Liverpool Railway.

Although George Stephenson was interested in the manufacture of cast-iron rails, he advised the management to lay down malleable iron rails. According to the specification drawn up by him, the rails were to be made from scraps of good English bars re-manufactured. They were to be made after Birkinshaw’s patent, 2 1/4 in. broad at the top, with a flange 3/4 in. thick. Fish-bellied in shape, they were 2 in. deep at the points where they rested on chairs, and – 3/4 in. in the middle or bellied part. Their weight was only 28 lb. to the yard. Their length averaged about 15 ft., and they were known among the workmen as 10 stone rails. The cast-iron rails weighed 56 lb. to the yard. Ultimately it was decided to order 800 tons of malleable rails; also 800 tons of cast-iron rails; the latter to be used for piecing out the line where the malleable rails fell short and for sidings.

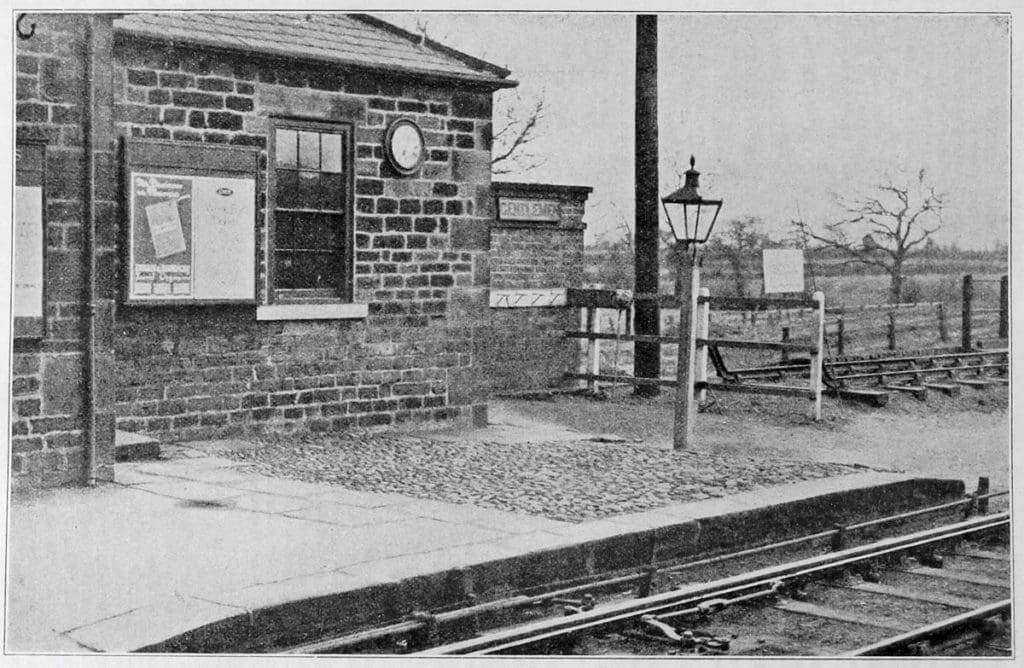

The rails having been ordered, the next point was as to the sleepers. The directors decided upon the extensive use of stone blocks for sleepers. These blocks at first were 18 in. square by 10 to 12 in. thick; but in 1835 the size was increased to 2 ft. square, and cost twopence each. Two holes were drilled through each stone block, and for drilling 24 blocks boys were paid 8d., which was Considered a fair day’s wage. But on the embankments blocks of wood were used, 2 ft. 6 in. long and 6 in. square. As time wore on the stone sleepers were gradually discarded, and used for edging platforms at country stations, and in 1882 Saltburn’s sea wall promenade was mainly formed with them.

It is interesting to note, too, that it was in 1823 that George Stephenson entered into partnership with Edward Pease and Thomas Richardson, in order to establish a locomotive building works at Newcastle-on-Tyne, this being the origin of the famous Forth Street Works, which eventually gave rise to the present firm of Robert Stephenson & Co. Ltd, now and for many years past located at Darlington. It was at the Forth Street Works that the first two locomotives for the Stockton and Darlington Railway were constructed, the order being given on September 16, 1824, the price to be £500 each. It is of interest to note that Timothy Hackworth, who was afterwards so closely associated with locomotive development on the Stockton and Darlington Railway, was at this time manager of the Forth Street Works.

Locomotion arrived at Aycliffe in the summer of 1825, having been brought by road from Newcastle, and, according to a history of the Stockton and Darlington Railway published by Messrs. Heavisides & Son, of Stockton-on-Tees, in 1912 (from which some of the items of information previously given are extracted), when the news came that “t’ iron hoss ” was on the way to Aycliffe, the whole population of that village turned out to witness its arrival, but when at last the strange-looking piece of machinery came in sight a general feeling of disappointment was expressed, and they said, “This the iron horse! Why, it is nothing but a steam engine set on wheels.”

At Aycliffe Level the engine was placed on the rails, and it is said that, no one having a light, the fire was kindled for the first time by means of a burning glass (in the possession of one of the navvies then present), and with the aid of tarred oakum. The publication just mentioned comments as follows: “The truth of this incident has been thoroughly corroborated, and thus, beyond all doubt, the first locomotive-engine that ever moved over a public railway was kindled on its first trial trip by the sun itself. Condensed sunlight, in the shape of coal, was waiting to be converted into heat in the furnace of the engine, and the kindling spark brought direct from the sun itself.”

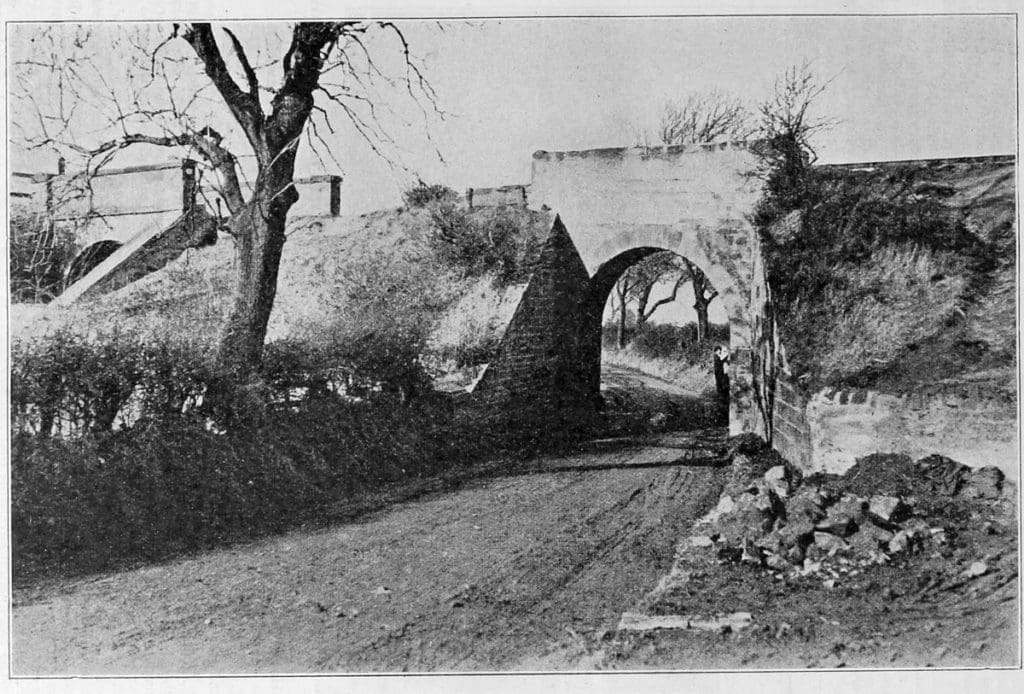

Apparently, although the name Puffing Billy strictly belongs to Blackett and Hedley’s engine constructed some years previously, No. 1 was often given that sobriquet. Incidentally, Locomotion seems to have been somewhat skittish when making her trial trips, in that one contemporary account describes her as “a runaway horse.” “She ran over hedge and ditch many a time (meaning she got off the line). When she made her trial trip there were wagons put to her for fear she could not be stopped on a dead flat.” The original line had sidings at frequent intervals, in some cases every quarter of a mile, with watering places here and there. There were a few bridges over the railway, one carrying the line over the River Skerne, said to be the first railway bridge ever constructed. There were, of course, no stations, merely yards here and there to form depots.

With regard to the opening ceremony, notices were issued in the local newspapers in the following terms :—

STOCKTON AND DARLINGTON RAILWAY

The Proprietors of the above concern hereby give notice that their main line of Railway commencing at Witton Park Colliery, in the west of this county, and terminating at Stockton-on-Tees, in the east, with the several branches to Darlington, Yarm, &c., being about 27 miles in extent. will be opened for the general purposes of trade on the 27th inst.

It is the intention of the Proprietors to meet at the Permanent Steam Engine, erected below the Tower at Brusselton, near West Auckland, and situate about 9 miles west of Darlington, at eight o’clock. a.m., and after inspecting their extensive inclined planes, then proceed, at nine o’clock precisely, by way of Darlington and Yarm, to Stockton-upon -Tees, where it is calculated they will arrive about one o’clock.

An elegant dinner will be provided for the Company who may attend, by Mr. Foxton, in the Town’s Hall, at three o’clock, to which the Proprietors have resolved to invite the neighbouring nobility and gentry who have taken an interest in this very important undertaking.

Any gentlemen who may intend to be present on the above occasion, will oblige the Company by addressing a note to their Office, Darlington, as early as possible.

A superior Loco Motive Travelling Engine, on the most improved construction, will be employed with a train of convenient carriages, for the conveyance of the Proprietors and strangers.

Railway Offices, Darlington, September 14, 1825.

It is of interest to note that Messrs. Heavisides’ “History” adopts the view taken by the Railway News, that the first passenger coach was of a caravan type. Moreover, their publication brings out the point that “The Experiment” arrived from Newcastle on September 20, 1825, that on September 26 it was coupled to “No. 1” at Shildon, and that Messrs. Edward Pease, sen., Edward Pease, jun., Joseph Pease, Henry Pease, Thomas Richardson, William Kitching and George Stephenson were the first passengers to travel in the first passenger carriage the first time in railway history. Further, the journey was made behind a locomotive engine, James Stephenson, brother of George, being the driver.

It is now necessary to describe again the proceedings associated with the opening ceremony, though even after this lapse of time, and bearing in mind the very great part played by the Pease family in connection with the fortunes of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, as also the North Eastern Company, one can sympathise on account of the fact that on the opening day Edward Pease had to mourn the death of his youngest son, Isaac, then 22 years of age. It was said, indeed, that the death chamber was within hearing of the cheers of the immense crowd which hailed the arrival of Locomotion and its lengthy train in Stockton. That explains why none of the Peases were present at the actual opening ceremony.

The “great day” necessarily attracted a tremendous crowd, a number of people coming many miles and by all manner of conveyances. The first item in the day’s programme was an inspection of the Etherley incline plane and its stationary, engine, prior to joining a train of 13 wagons, 12 laden with coal and 1 with flour assembled at the foot of Brusselton incline. The wagons were then hauled by cable up the incline, and at the top the Brusselton engines were inspected. The wagons then descended the incline on the other side, presumably by gravity, to a point where locomotion was waiting to take charge. Its train included “The Experiment” coach, described as arranged so that the passengers sat face to face along each side; that it would carry 16 or 18 inside, and that it was intended to travel for public accommodation between Darlington and Stockton. On the opening day it was reserved for the Railway Committee and their friends. The make-up of the train was thus described officially :–

The Company’s Locomotive Engine. The Engine’s Tender, with water and coals. Five waggons, laden with coals and passengers. One waggon, laden with flour and passengers. One waggon, containing surveyors, engineers, etc. “The Experiment,” containing the Committee and other Proprietors. Six waggons, with strangers seated. Fourteen waggons, with workmen and others standing. Six waggons, laden with coals and passengers.

It was recorded that when Locomotion began to blow off steam, some consternation was created among the spectators, the general effect being thus described by a somewhat imaginative reporter of the period:- “The locomotive, or steam horse, as it was more generally termed, gave a ‘note of preparation’ by some heavy respirations, which seemed to excite alarm among the “Johnny Raws,” who had been led by curiosity to the spot, and who, when a portion of the steam was let off, fled in affright, accompanied by the old women and young children who surrounded them, under the idea, we suppose, that some horrible explosion was about to take place. They afterwards, however, found courage to return, but only to fly again when the safety valve was opened.” George Stephenson, his brother James and another member of the family, Ralph, were in charge of the engine, and apparently Timothy Hackworth acted as a kind of guard.”

The general impression appears to be that Locomotion could not manage much more than six or eight miles an hour, but one of the descriptions of the proceedings of that day suggests that “gentlemen riding hunters” alongside the railway across country were not able to keep up with the engine, at least not while it was on favourable gradients. Before reaching Darlington, the first incident was the derailment of one of the wagons – that containing the surveyors and engineers. This difficulty was soon overcome, but after a second derailment the faulty wagon was shunted to a siding. At Simpasture the tram came to an unexpected stop and many of the passengers hurried to the engine to find out what had happened. “Some oakum had got into the feed pump, that was all; it would soon be all right.” This difficulty remedied , the journey to Darlington was resumed, and on Aycliffe Level it is recorded that the rate of 15 miles an hour had been reached. In due course the train entered Darlington, complete as it had left Shildon, except for the one wagon which had been removed. About two hours had been occupied in covering a distance of nine miles, though, in fairness, it must be remembered that there had been three stoppages, lasting altogether 55 minutes.

At Darlington, where a halt for half-an-hour was made, six wagons of coal were taken off and other wagons, containing a band, coupled on. The train carried, however, many more passengers than those for which it had accommodation, in that people clung on to the wagons or the train in every conceivable way. Except for a stop at Goosepool for water, the run to Yarm and onwards to Stockton was made without difficulty. It is recorded, however, that Locomotion, with her train of thirty wagons and with some 600 or so passengers, raced a stage-coach bound for Stockton, drawn by four horses and carrying 16 passengers all told, which was then passing on the main road which was parallel with the railway. Proceedings were then transferred to the Town Hall in Stockton, where it is recorded that 102 gentlemen sat down to a very excellent dinner.

It is now necessary to consider the general features of the Stockton and Darlington Railway. The railway commenced by connections with the Witton Park and Etherley Collieries. For the first mile the wagons were drawn by horses to the foot of a hill called Etherley Ridge. The height of this was about 646 ft. above sea level, and as the collieries were about 470 ft. above sea level, the rise to the summit was overcome by means of a hauling engine. On the opposite slope the wagons descended by gravity a distance of 312 ft., but the cable was used to govern the descent of loaded wagons as well as for hauling up the empties. At the foot, horses were again employed for the distance of about 1 1/4 miles to the foot of Brusselton Hill. Here another steam engine was utilised to haul the wagons up the slope of nearly a mile, achieving a vertical rise of some 150 ft., while on the other side the wagons descended by gravity under cable control for about half a mile, representing a vertical distance of 90 ft. There were two hauling engines at each summit. those at Etherley Ridge being of 15 h.p. and those at Brusselton Hill 30 h.p. each. The two engines operated, one winding drum in each case, and an extra charge of 6d. per ton for the use of machinery was made for working over the incline. On the opening of Shildon tunnel in 1842 this mode of working was discontinued. The remainder of the route was sufficiently level to admit of being worked either by horse or by locomotive power. About two-thirds of the line was laid with malleable iron rails 18 ft. long and weighing 28 lb. to the yard. The remainder used cast-iron rails 4 ft. long and weighing 57 1/2 lb. to the yard. On the inland sections the rails were laid on stone blocks, and on the Stockton division upon oak blocks.

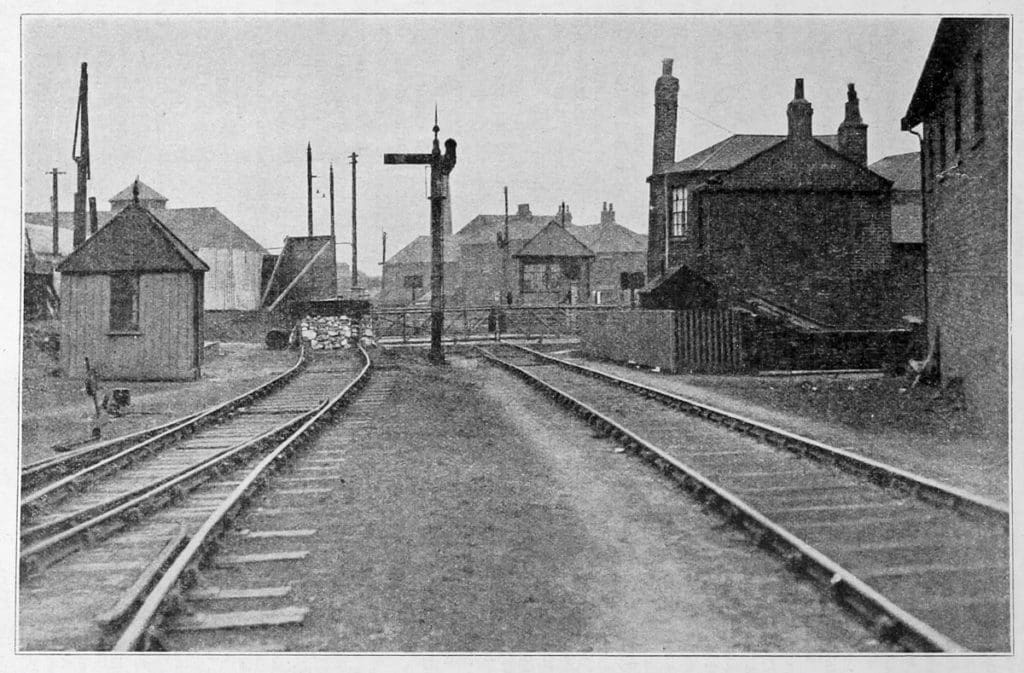

Referring again to the question of passenger rolling-stock, the original caravan-like passenger coach seems to have proved a failure as an “experiment,” as within a few weeks a more satisfactory type of coach was introduced. The new vehicle was apparently of stage coach type, and this explains why the fares were, inside 1 1/2 d. per mile, and outside 1d. The original service provided for a coach on Mondays, Wednesdays, Thursdays and Fridays from Stockton at 7.30 a.m., returning from Darlington at 3 p.m., while on Tuesdays there was a service. from Stockton at 3 p.m., and on Saturday one from Darlington at 1 p.m., with apparently no return service—at least, none was publicly advertised. As first announced, the round fare was 1s. per passenger, so that, presumably, the inside and outside fares already quoted were not instituted until after the inauguration of regular passenger services. Passengers had a free luggage allowance of 14 lb., paying at the rate of 2d. per stone extra, while small parcels were conveyed at 8d. each. As the traffic grew, two coaches were in use, and one writer suggests that posts erected between the crossing place – the vehicle first reaching the post having precedence, while the other had to be drawn back to the next crossing – represent the first attempt at railway signalling and regulation.

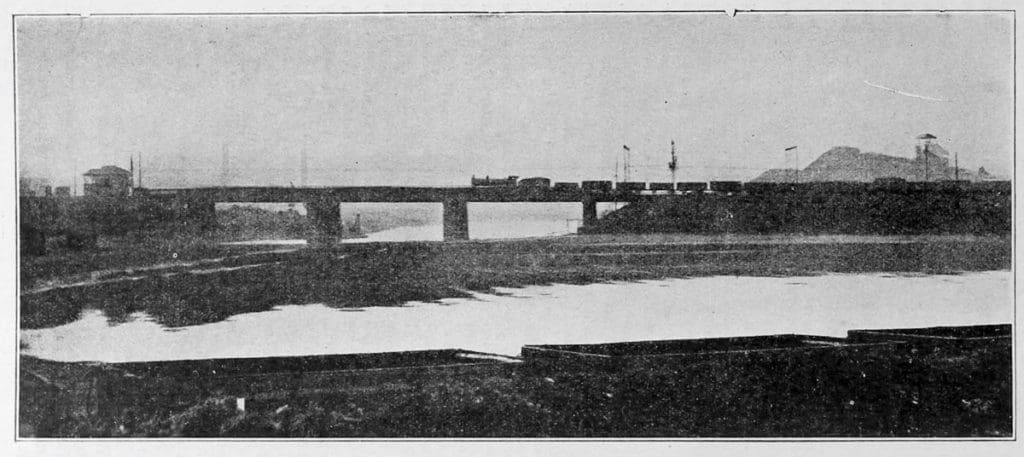

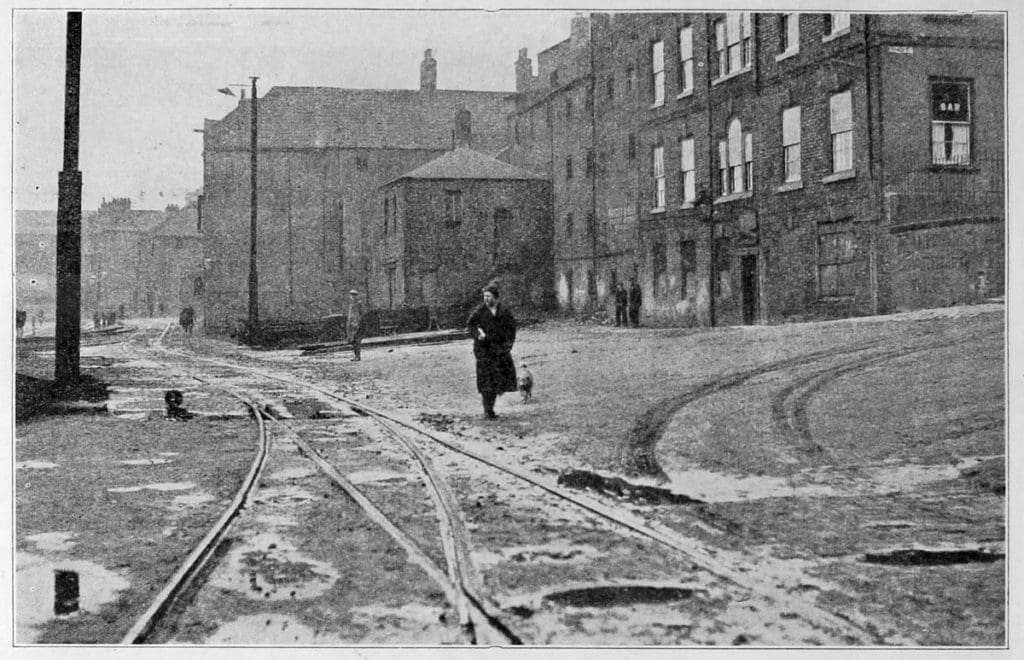

One of the first extensions of the original line was a 4-mile route from Stockton to Middlesbrough. The Parliamentary Act covering this, as also the making of quays and coal staiths at Middlesbrough, was passed in 1828. The line was opened on January 1, 1831. There was a very crude iron bridge on the original line which is often referred to as the first iron railway bridge ever constructed, and on the Middlesbrough extension what was probably the first suspension bridge to be erected for conveying railway traffic was built. It was 274 ft. long, 25 ft. broad, and 60 ft. in height, and calculated to sustain a weight of 150 tons. It was not however, successful, in that it proved unable to carry the traffic contemplated, so that during the period it was in use the weight of trains crossing it had to be severely limited. Indeed, it is said that after a time it was necessary to work traffic across it one loaded wagon at a time, until, in 1844, a new and stronger bridge was available. It may be pointed out that, although Stockton was a town of some importance, Middlesbrough was little more than a “dismal swamp.”

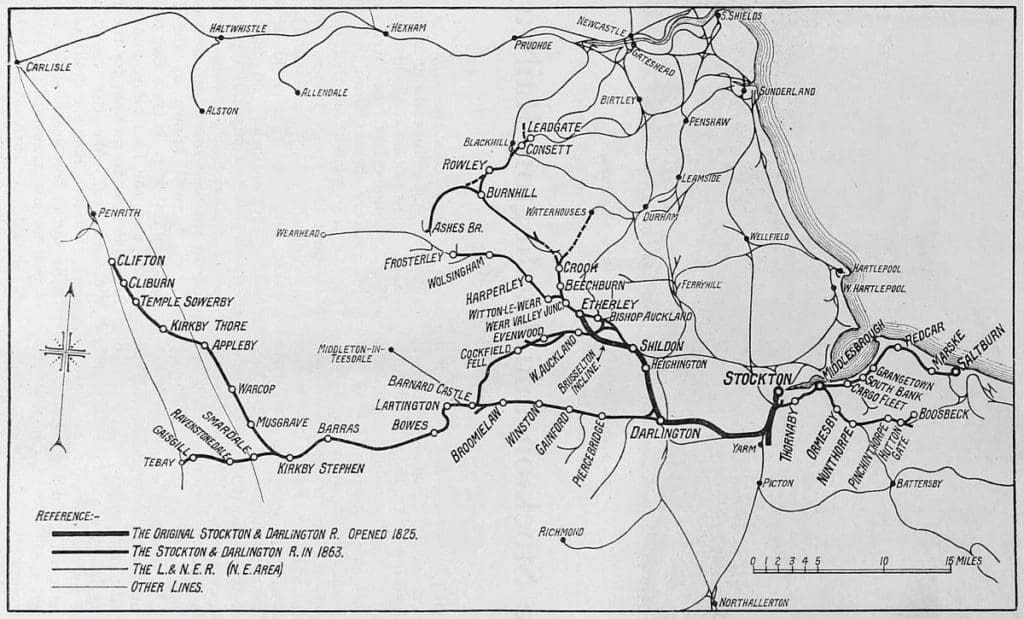

The next extension at the eastern end of the Stockton and Darlington Railway was not taken in hand until 1845 when a Bill was obtained for a line from Middlesbrough to Redcar, a distance of about eight miles. This was opened on June 4, 1846, and once again the engine Locomotion had the honour of inaugurating traffic. In 1858 powers were obtained to extend to Saltburn. At the western end, however, several branches and extensions were carried out in the Bishop Auckland district in order to serve various collieries and limestone works. These included the Bishop Auckland and Weardale, Wear and Derwent and Weardale Extension Railways. These, together with the Shildon Tunnel undertaking, were amalgamated in 1847 with the Wear Valley Railway Company, incorporated in 1847. They were all associated with the Stockton and Darlington Railway, and in 1847 were leased by that company, together with the Middlesbrough and Redcar Railway.

Further extensions relate to the development of the Cleveland iron district south of Middlesbrough. In this connection, a line was opened from Middlesbrough to Guisborough, this becoming eventually one of the most important sections of the system, so far as the iron traffic was concerned. At the western end, powers were obtained in 1854 for the construction of the South Durham and Lancashire Railway to Kirkby Stephen and Tebay, thus connecting with the London and North Western and Midland Railways. Eventually the tendency towards amalgamation affected the Stockton and Darlington itself, and by an Act which received Royal assent on July 13, 1863, the Stockton and Darlington was taken over by the North Eastern Company.

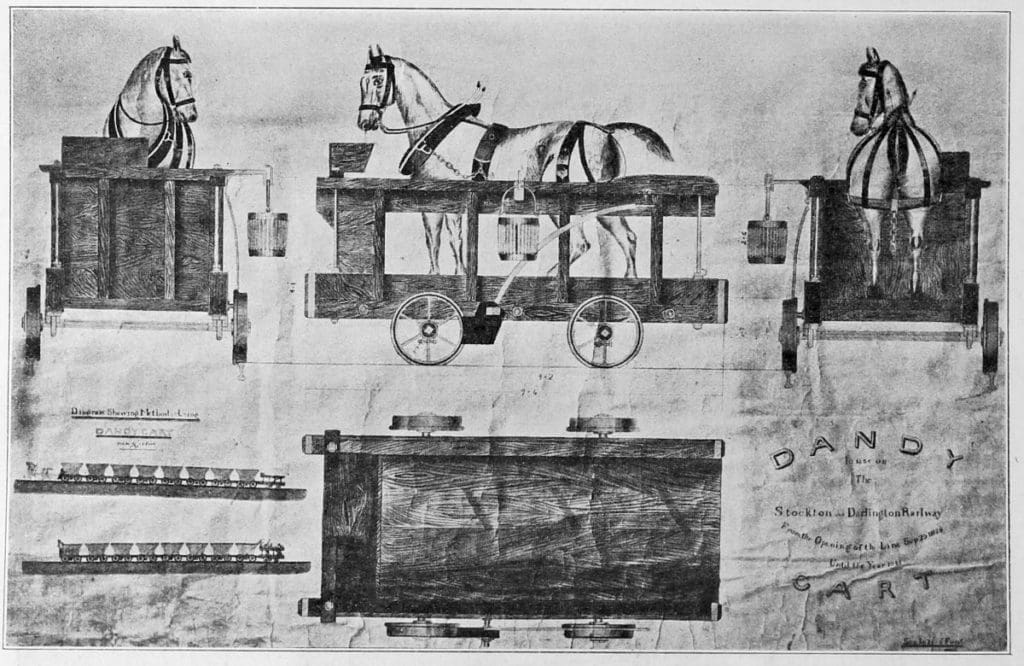

Several incidental matters of interest may now be briefly referred to. The original horse—drawn passenger coaches were all, apparently operated by contractors, and it was not, indeed, until 1843 that their use entirely disappeared. The early passenger carriages were not, however, greatly superior to the stagecoach vehicles of the horse era. They included open carriages, such as those which remained in use on some lines for a number of years for the conveyance of third-class passengers, and covered carriages with seats along each side and a double row along the middle. Next came a type of coach containing five compartments, with backs extending only to the level of passengers’ heads, subsequent developments following substantially the same lines as on railways generally. It is said that in early days tickets were printed in different colours varying for each day of the week, without date or number, and that the guards wore red frock-coats with brass buttons. Until 1835 “there was no railway station” on the line, the trains drawing up at a terminus, while passengers purchased their tickets at a ticket-office in an adjacent building, entraining or detraining on ground level. Apparently, the last instance of horse traffic remaining on the railway was a service given on Sundays from Stockton to Middlesbrough and back until 1856. During this period, on the section where horses were still used, the famous horse dandies were employed. These were attached at the end of a train of Wagons, and the horses were trained to jump in on their own account on the down gradients, and thus ride as passengers until their services were again required to “head” the load.

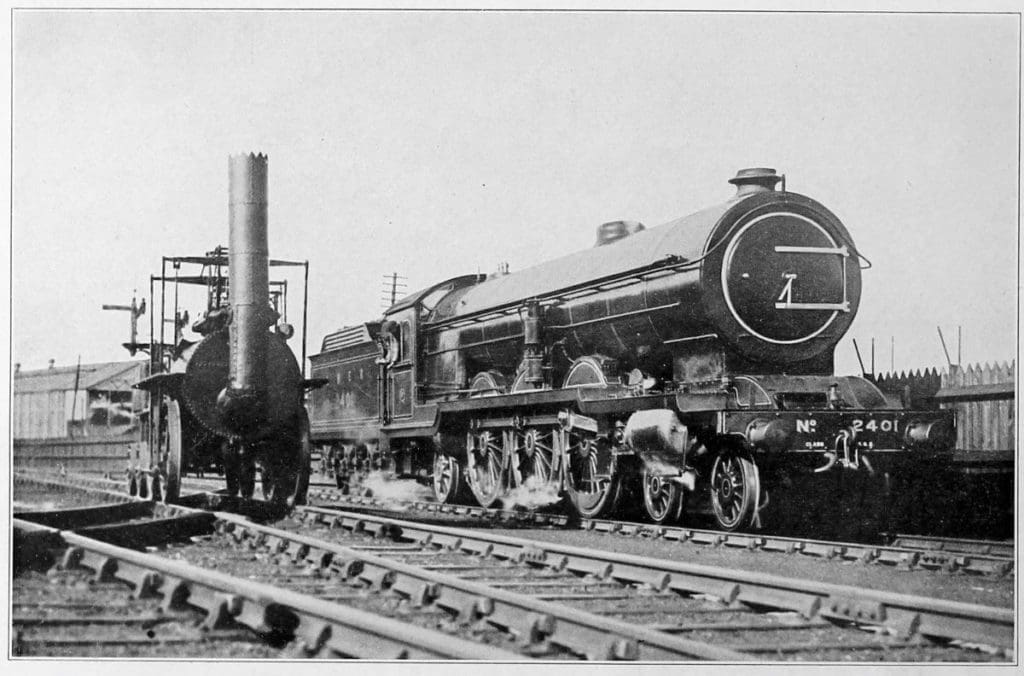

Although one engine only was available for the opening ceremony in September, 1825, the famous Locomotion, another one, named Hope, was placed in service in November of that year, and in April and May, 1826, Black Diamond and Diligence were added. These four engines were generally similar in design. The next addition was a somewhat mysterious engine named Chittaprat, which was built by Robert Wilson, and said to have had four cylinders. The boiler was subsequently used for No. 5, Royal George, a 0-6-0 engine. No. 6 was supplied in January, 1828, and bore the name Experiment. It was later altered to a 0-6-0 engine. The Royal George, No. 5, differed essentially from other engines in service. It is, indeed, regarded to this day as a big advance upon previous locomotive practice, and its excellent service constitutes one of the principal achievements to the credit of Timothy Hackworth. It was a six-coupled engine with vertical cylinders driving directly the rear coupled wheels, and ranked as the most powerful engine which had been built until then. Its construction, however, required a tender at each end.

Next came an engine (No. 7) which bore the name Rocket. This was originally placed on four wheels, but apparently the weight was too great for the rails, and it was subsequently rebuilt as a six-wheeled engine. In view of divergences between various historians, it seems possible that The Royal George itself at first had four wheels only, and was converted to six-coupled later. The Rocket seems to have been not unlike its more famous namesake on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, in that it had diagonal cylinders at the firebox end driving the leading wheels, very much in the style familiar in the Liverpool and Manchester engine. No. 8, Victory, was another Hackworth engine generally similar to The Royal George. In 1833 the engine was rebuilt and continued at work for another ten years or so, when it was replaced by a new No. 8, also of Timothy Hackworth’s design, named Leader.

For the opening of the Middlesbrough and Redcar line, a six-wheeled single-driver engine, having driving wheels behind the carrying wheels and known as “A.” was an interesting development. By about 1840, however, the locomotives added to the Stockton and Darlington stock began to correspond generally with the types familiar on most railways in that period. There was at least one of the famous “Bury” class, so familiar on the London and Birmingham Railway, but the standard Stockton and Darlington engines gradually became 2-4-0 passenger and 0-6-0 tender locomotives of more or less orthodox type. A peculiarity for many years, however, was that all wheels were placed in front of the firebox and usually very close together, so that the engines gave an impression of unwieldiness owing to their apparently excessive overhang at one or both ends. For some time after amalgamation with the North Eastern Company the Stockton and Darlington section was operated more or less on its own account, and in some respects it may be said that the engines built at Darlington from 1883 to the early ’seventies, including those to the designs of Mr. W. Bouch, belonged more particularly to the history of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, although built and operated as North Eastern stock.