The United States is renowned as a world leader in technology, and sent the first manned space missions to the moon half a century ago. Yet the first steam railway locomotive to run in the US was built in Britain – at a foundry in the West Midlands.

This is just one of the many in-depth features found in the new book by Robin Jones, Legendary Locomotives, available now from Classic Magazines.

Britain invented the self-propelled railway locomotive, believed to have been first built by Cornish mining engineer Richard Trevithick at Coalbrookdale in 1802 and successfully publicly demonstrated by him on the Penydarren Tramroad in South Wales two years later.

At the time, railways were horse-drawn affairs, the purpose of which was to link collieries and foundries to the nearest waterway or harbour. At first, Trevithick’s inventions were considered more of a novelty than a series form of everyday transport, but in the next decade, many industrialists and their attendant engineers began to take a second look at his concept.

Horse-drawn tramways by then had been in use in Britain for two centuries or more, but it was only in the 1820s that the idea of railroads being used as an essential form of transportation in the United States attracted serious interest. By that time, several horse-drawn or incline railways were in the process of being built.

In 1823, the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company, which became the Delaware & Hudson Railway, was authorised to carry anthracite from the coalfields around Carbondale, Pennsylvania to New York City via a set of cable-operated incline railways powered by stationary steam engines.

The company’s original name came about because its first plan was to build a canal over the entire distance, but two years later, engineers began to consider railways, too.

John Bloomfield Jervis was appointed as the company’s chief engineer in 1827, and drew up a scheme for a series of inclines linked by level railways over a distance of 17 miles. The company was impressed and gave him the go-ahead to build it, despite the fact rail technology had still not yet considered to have been wholly proven.

He sent his deputy engineer Horatio Allen to Britain on a railway fact-finding mission – and brought with him Jervis’ specifications for locomotives that could be ordered for the Delaware & Hudson. Even though Allen was just 25, he was authorised to buy four locomotives if he felt they would be suitable.

In England, he met locomotive engineers Robert Stephenson and John Urpeth Rastrick of Foster, Rastrick & Company.

Rastrick had been there as near as might be possible to the dawn of the railway age. Born in 1780 at Morpeth in Northumberland, he completed an apprenticeship with his father, including work on steam engines. He worked first at the Ketley Ironworks in Shropshire and then formed a partnership with John Hazledine of Bridgnorth.

It was at Bridgnorth he built the world’s first locomotive to haul fare-paying passengers – Catch-me-who-can, for Richard Trevithick. The locomotive and a carriage famously gave public rides on a trainset-style circle of track near the future site of Euston station in London.

In 1817, Rastrick left the partnership with Hazledine’s company and moved to West Bromwich in the Black Country. June 1819 saw Rastrick and James Foster form Foster, Rastrick & Company at a site next to the Stourbridge Iron Works. There, a new foundry was constructed from 1820/21 to produce products for the partnership.

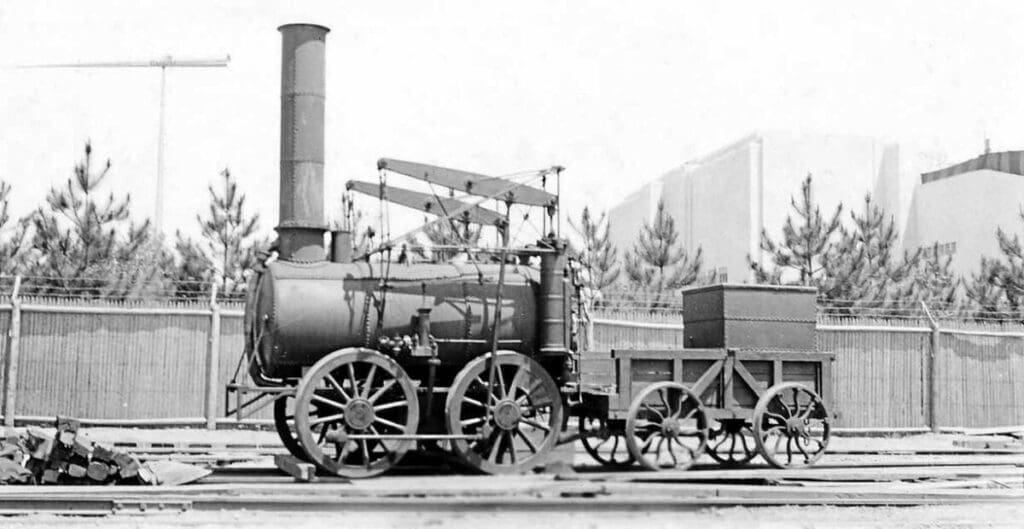

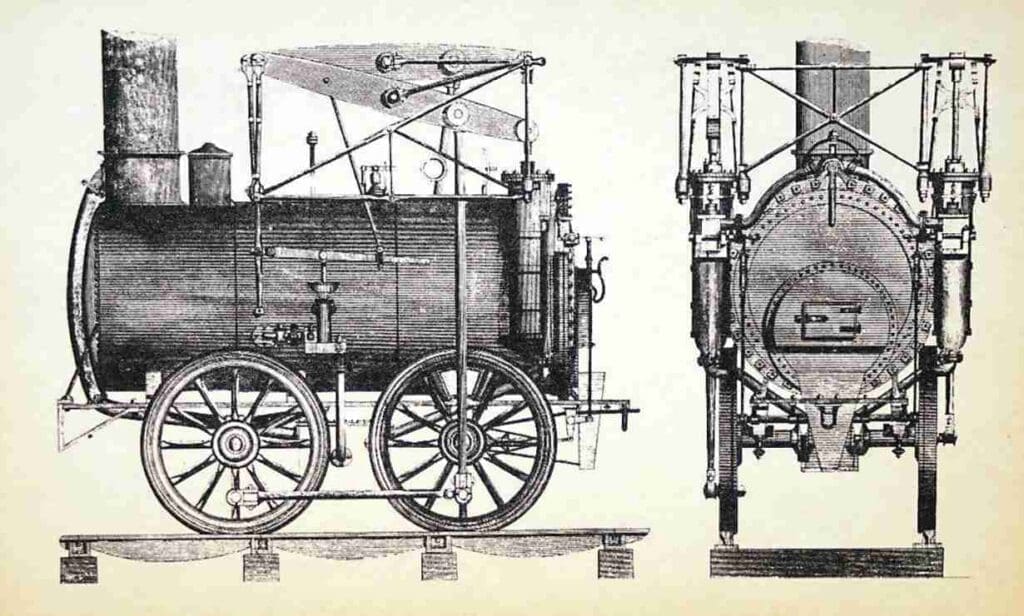

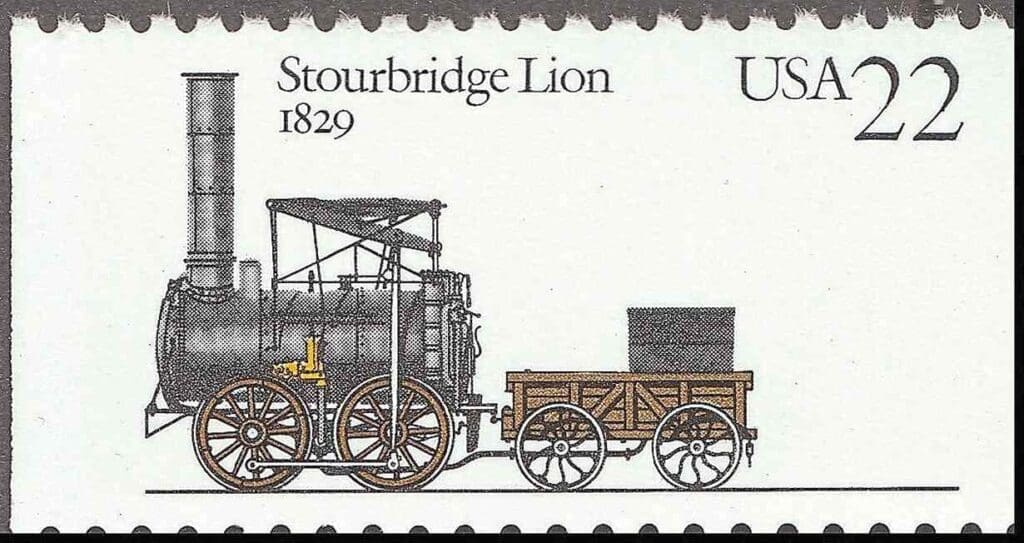

Allen wrote back to Jervis to let him know he had ordered four locomotives to be shipped to the Delaware & Hudson. There was one from Robert Stephenson & Company of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, the Pride of Newcastle, and three from Foster, Rastrick & Company, including the Stourbridge Lion.

While in England, Allen also ordered 290 tons of scrap iron from a foundry in Wolverhampton to help build the US line.

It was Stephenson’s works which completed the first of the four locomotives, and it arrived in the USA nearly two months before the first from Foster, Rastrick, the Stourbridge Lion, which cost $2,914.90, was delivered to the States.

‘Lion’ was transported as a kit of parts from Liverpool aboard the ship John Jay and arrived back in New York on May 13.

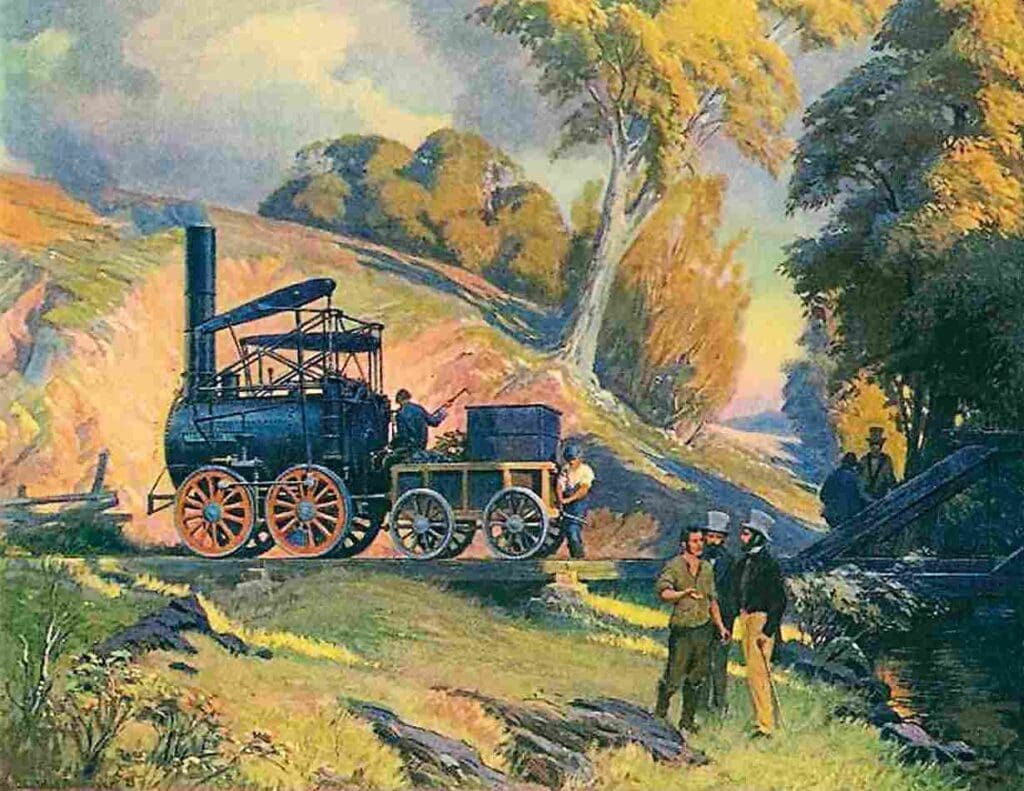

It was then sent to the West Point Foundry, based in nearby Cold Spring, for reassembly and testing. US history was made when its trials began on August 5 and ‘Lion’ was shown to be in working order; it was also attracting thousands of sightseers who wanted to see it move.

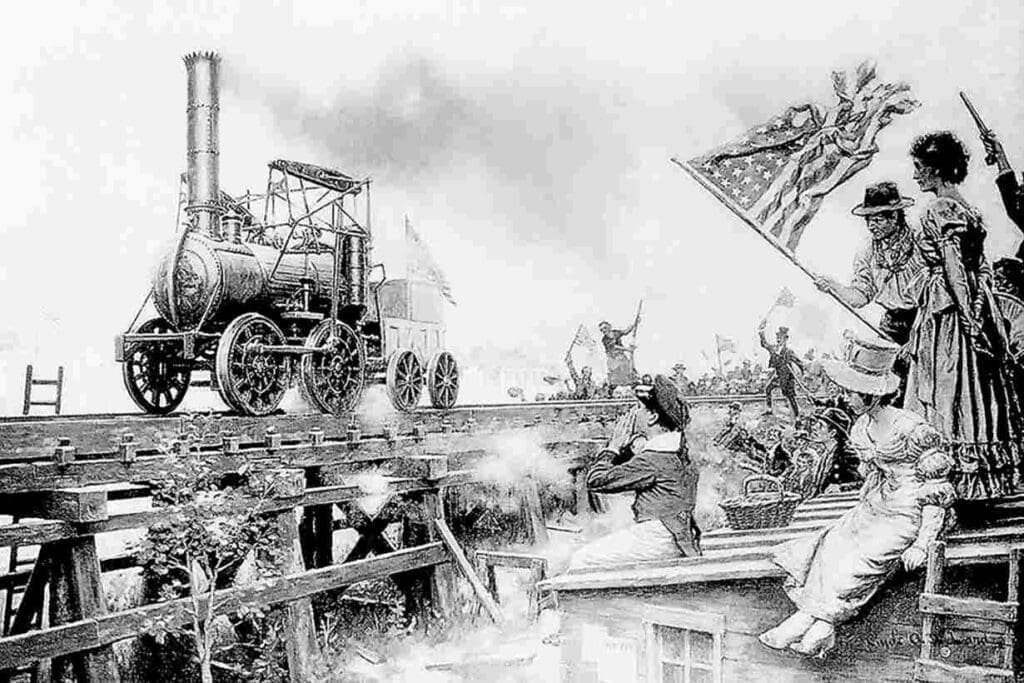

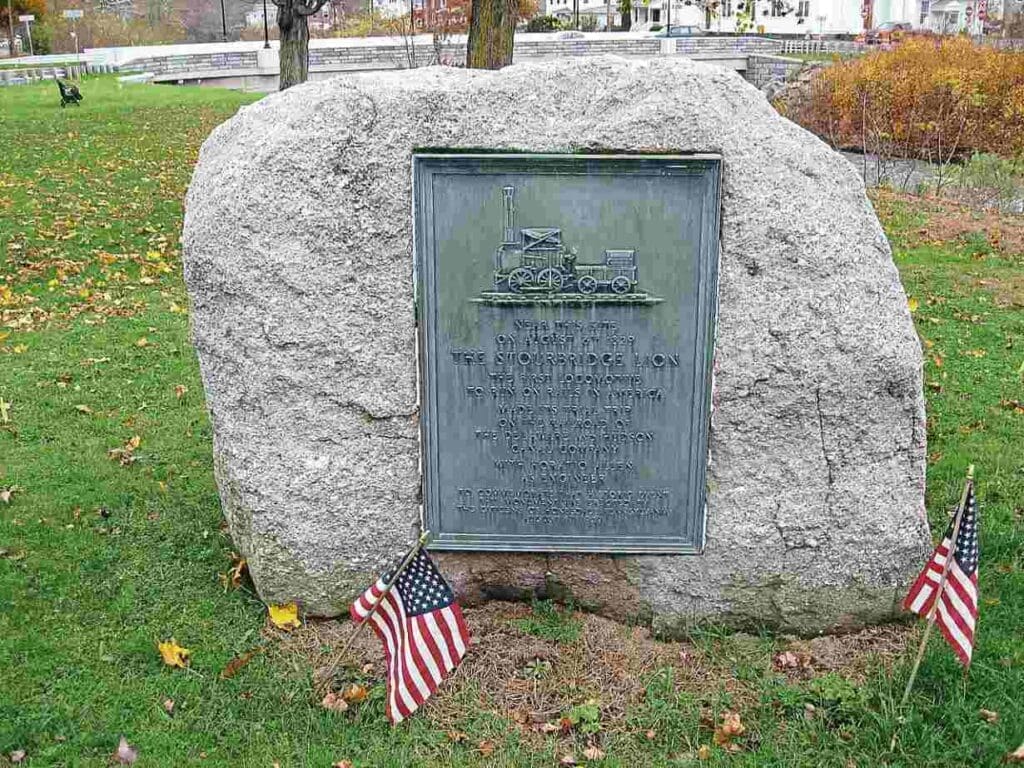

August 8, 1829, saw ‘Lion’s’ first official run along the completed length of line in Honesdale, Pennsylvania, with Allen in charge.

It was reported ‘the fire was kindled and steam raised, and, under the management of Horatio Allen, the wonderful machine was found capable of moving, to the great joy of the crowd of excited spectators’.

Allen had no experience of driving a locomotive but he took the controls of the ‘Lion’, and invited spectators to ride with him. Wary of this strange beast, the like of which had never been seen running in America before, none of the crowd accepted the invitation.

Allen ran the Stourbridge Lion up and down the coal dock several times, pulled the throttle valve open, yelled farewell to the throng, and dashed away around a curve and over the raised trestle section that crossed Lackawaxen Creek at 10mph.

He drove the ‘Lion’ for three miles along the track accompanied by the welcoming cheers of the crowd, the waving of flags and the booming of cannon, before reversing it back to its starting point.

Yes, the Stourbridge Lion was in roaring good form, but sadly the track was not up to scratch. Jervis had stipulated the engines should not weigh more than four tons, but ‘Lion’ weighed 7.5, and that proved its undoing.

‘Lion’ would never run along the track again. Soon, labourers began laying wooden planks between the rails so horses could pull wagons along it instead.

The two other Foster, Rastrick engines – Delaware and Hudson – arrived separately at New York in August and September 1829 before being shipped on to Rondout, and from there taken by canal to Honesdale.

As the canal company could not afford to buy iron rails, the Stourbridge Lion was housed in a shed after this impressive trail run and dismantled in 1834, so the boiler could be used in a local foundry in Carbondale. An attempt to sell all three Foster, Rastrick engines to the Pennsylvania Canal Commission proved fruitless, and the four locomotives ended up being used as a source of bar stock metal.

By that time, the railroad concept had become established in the US and the four were considered obsolete. US railroads were now building their own steam locomotives to far better suit their growing needs.

The first regular passenger railway in the USA to use steam locomotives was the Charleston & Hamburg, of South Carolina, which was authorised in 1827. On this line the first locomotive built for service, an engine called the ‘Best Friend,’ was running in December, 1830.

Yet a locomotive built in the West Midlands had made US history, and would never be forgotten – even though it never ran again.

Seeing steam was not to be used on the Delaware & Hudson, Allen moved to the South Carolina Canal & Railroad, where he became chief engineer in 1830.

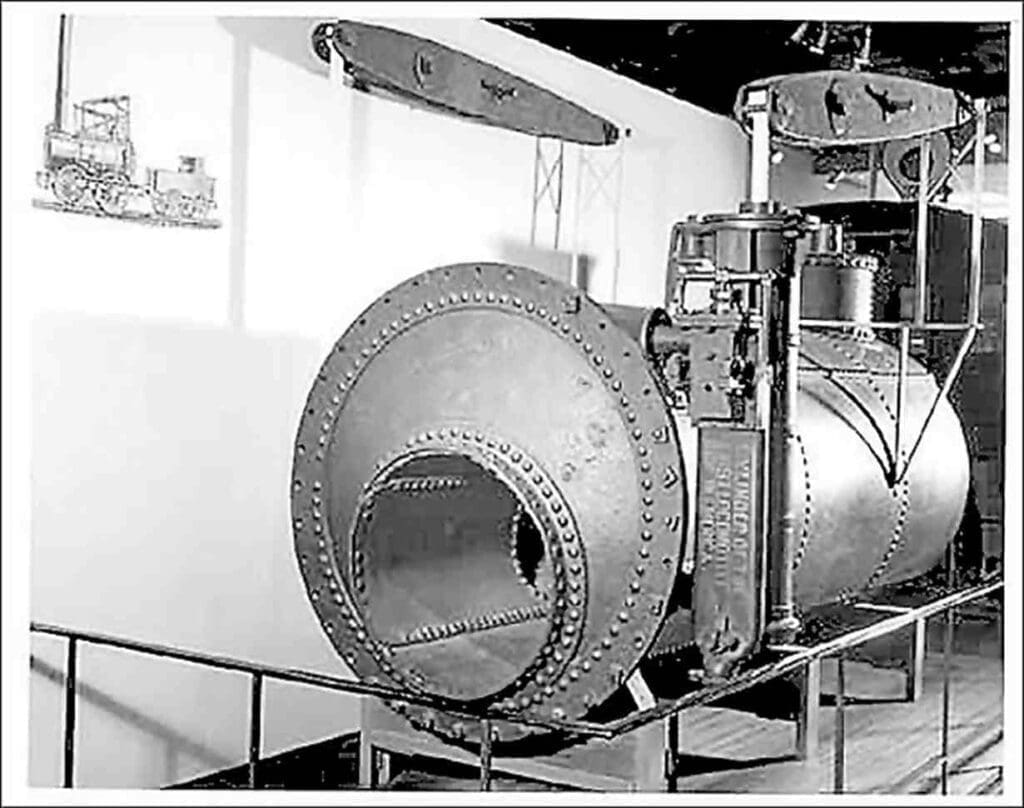

The remains of the Stourbridge Lion passed into many hands over the ensuing decades.

In 1883, the Delaware & Hudson borrowed the boiler for display at the Exposition of Railway Appliances in Chicago. Sadly, a lack of security around the boiler’s transportation allowed souvenir hunters, conscious of ‘Lion’s’ history, to pull every loose item that they could off the now historic boiler, even resorting to hammers and chisels to remove parts of it.

What was left of the boiler was eventually acquired by the Smithsonian Institution in 1890, but the boiler had been badly damaged through years of use, neglect, and vandalism.

Some other components thought to have come from the Stourbridge Lion are also preserved, but experts conjecture they may have come from the sister engines.

The museum has made a few attempts to rebuild the locomotive with the parts that remain, but because other components are lacking, the locomotive’s reconstruction has never been completed.

The Delaware & Hudson constructed its own replica of the Lion from drawings, based on the parts remaining in existence, to run at the 1933 Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago.

The replica was relocated to Honesdale in 1941, and is now based at the Wayne County Historical Society Museum, which is located in a small brick building in Main Street, Honesdale, Pennsylvania, once a Delaware & Hudson Canal’s Company office, and where the Stourbridge Lion started its maiden run.

A bid was made to steam it again in 2004, but the high cost of insurance was too high a deterrent, and also, the replica would need to be brought up to modern safety standards.

‘Lion’s’ boiler is now on loan to the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Museum in Baltimore.

Also, a replica built by the Delaware & Hudson, using the original ‘Lion’ blueprints, is based in Honesdale.

In October 2009, the US-based Trains magazine announced a project to build a full-size Stourbridge Lion replica had been launched.

Stourbridge Lion’s half-sister closer to home

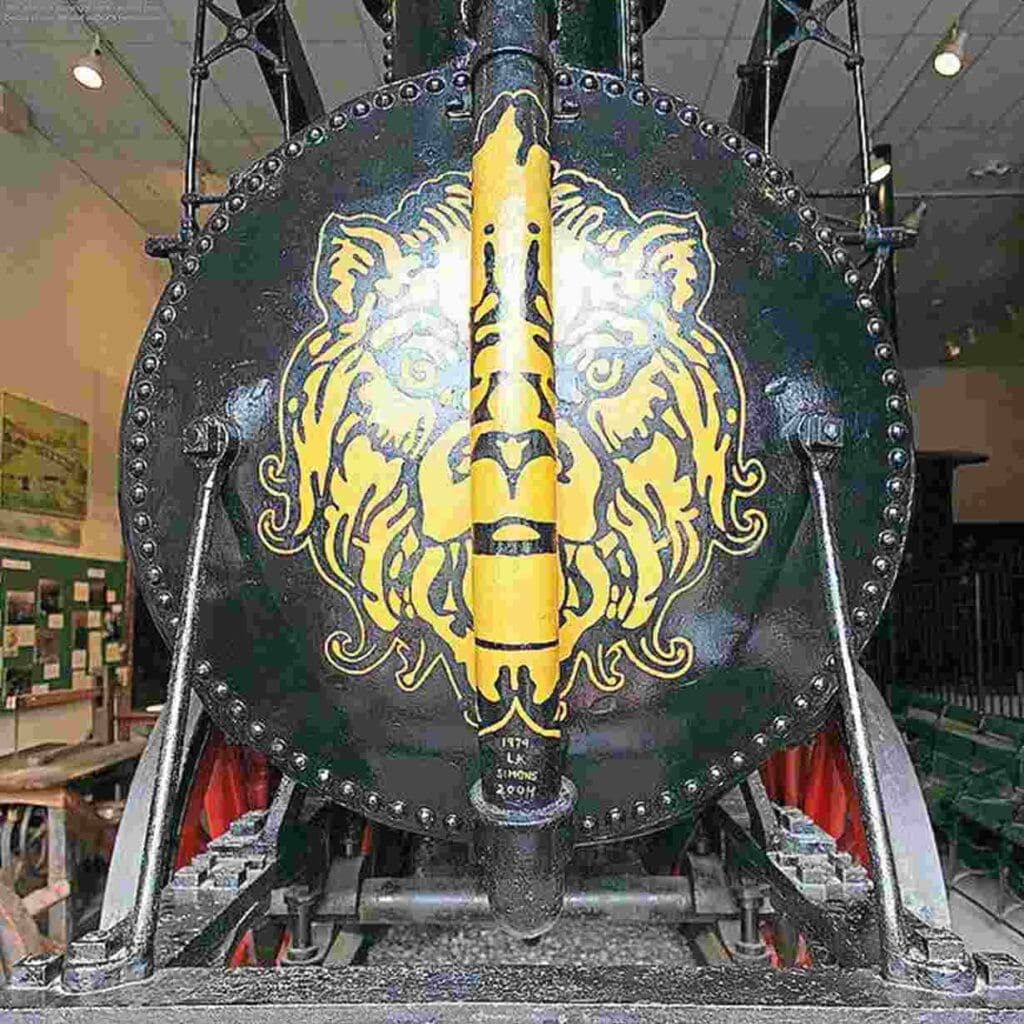

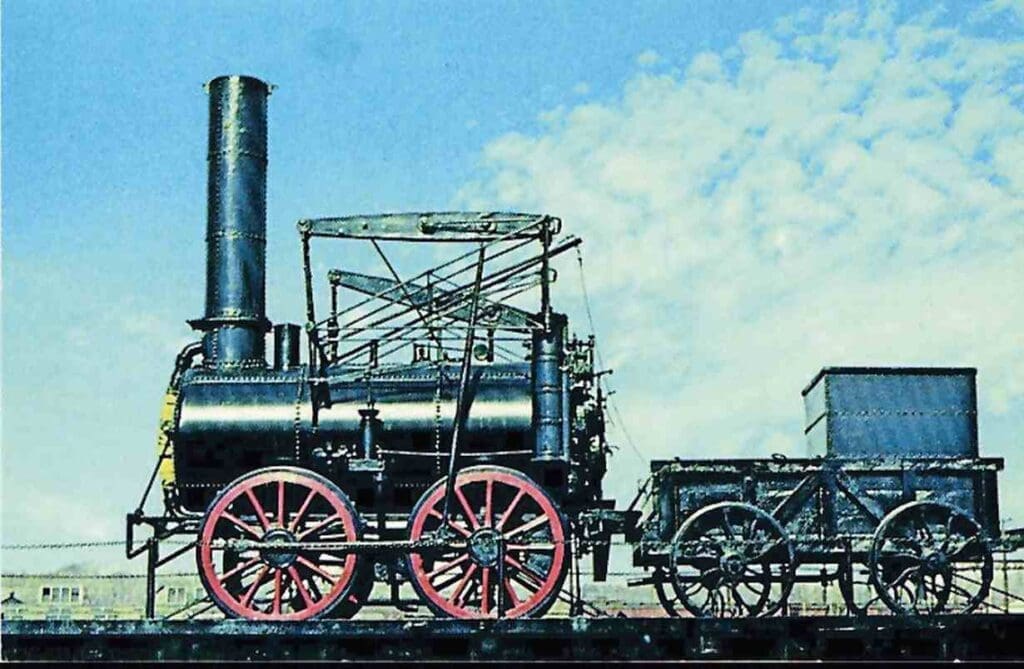

A ‘half sister’ locomotive of the Stourbridge Lion was built by Foster, Rastrick, but this time for use in England.

In 1823, James Foster leased land at Shutt End, Kingswinford to exploit the mineral deposits there and built an ironworks. He wrote in 1825 to local landowner John William Ward, the 4th Viscount Dudley, proposing to build a railway to transport minerals from both their lands.

Accordingly, in 1827, an agreement to construct a standard-gauge railway between Shutt End colliery and a canal basin at Ashwood on the Staffordshire & Worcestershire Canal, was signed.

Agenoria had a much longer chimney than the Stourbridge Lion, with its name taken from the Roman goddess of industry.

It first ran when the line opened on June 2, 1829.

The opening day attracted crowds of spectators. Agenoria’s first run saw it haul eight carriages filled with 360 passengers at 7.5mph. A second demonstration saw it pull 20 carriages, 12 filled with coal and eight with passengers, at 3.5mph.

For its final test of the day it ran for a mile with just the tender attached, carrying 20 passengers, reaching 11mph.

Agenoria ran in service on the line until the mid-1860s, with a replacement arriving in 1865.

Half forgotten and neglected, it was rediscovered on the colliery site, disassembled and covered with rubbish. One of its cylinders had been removed and used as a pumping engine.

It was reassembled and displayed at an exhibition in Wolverhampton in 1884, after which Foster gave it to the Science Museum in London.

Agenoria was loaned to the LNER’s museum at York in 1937, and in 1951 was an exhibit at the Festival of Britain.

It returned to York in 1974 and is now displayed with a replica tender in the Great Hall of the National Railway Museum.