The world has been in mourning for East Somerset Railway founder David Shepherd, who died aged 86 on September 19 2018, after losing a 10-week fight in hospital with Parkinson’s Disease.

After becoming an international wildlife artist and later a leading conservationist, he also bought two steam ‘beasts’ from British Rail in 1967 and helped transform our rail landscape, writes Robin Jones.

One of three children, Richard David Shepherd CBE FRSA FGRA was born on April 25, 1931, in Hendon, north London, the son of Raymond Shepherd, an advertising man, and Margaret (nee Williamson), a housewife.

From the history of steam through to 21st century rail transport news, we have titles that cater for all rail enthusiasts. Covering diesels, modelling, steam and modern railways, check out our range of magazines and fantastic subscription offers.

He was sent to Stowe school in Buckinghamshire, where he underachieved academically and also developed an intense dislike of the school sport, rugby.

He left school as soon as he could, and his father financed a trip to Kenya where he could realise his big ambition of becoming a game warden, only to be immediately told by the head game warden in Nairobi he was not wanted.

He came home after working as a hotel receptionist on the Kenyan coast, and considered two career paths – a job as a bus driver, or as an artist. He applied for a place at the Slade School of Art in London… where he was told that he had no talent for art.

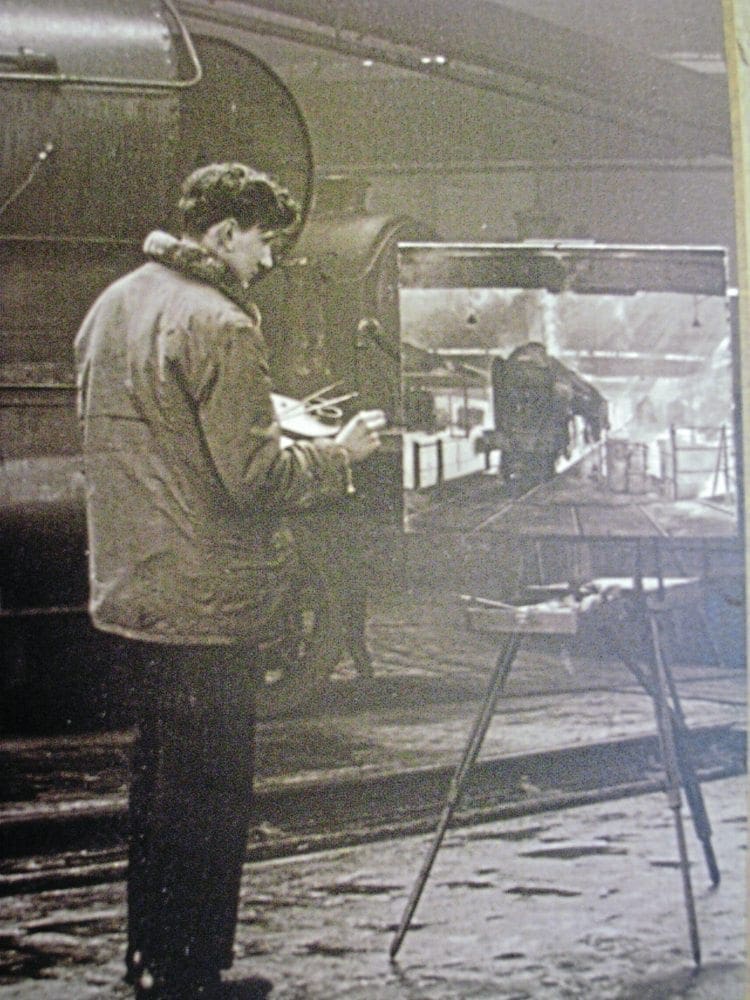

By chance at a party he met Robin Goodwin, a jobbing marine artist who took him on as an assistant at his studio in Chelsea, where portraits and marine subjects were painted. By 1953 Goodwin had taught David everything he could.

David contributed to the annual exhibition of artists’ work on the railings of the Victoria Embankment, and specialised in aviation subjects.

He painted aeroplanes at Heathrow and won commissions from airline companies. During this time he met Avril Gaywood, a secretary for Capital Airlines, and the couple married in 1957.

Never looked back

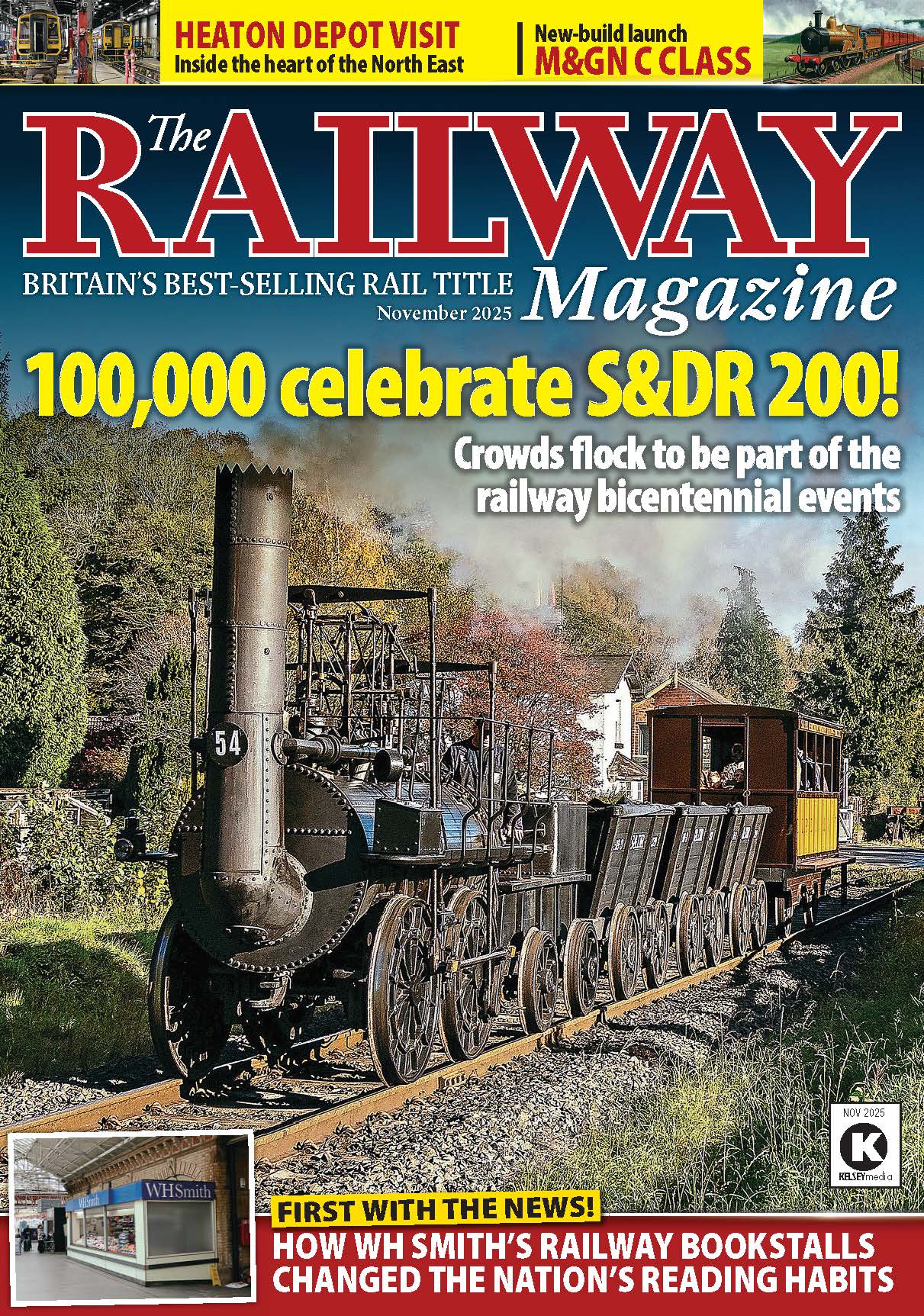

In 1960 the RAF flew him to Aden, not to paint aircraft but to capture the life of the country on canvas. He painted a rhinoceros chasing an aeroplane on a runway, and never looked back. He went on to paint elephants, tigers, lions, giraffes, cheetahs and zebras.

On that visit he became a conservationist, after finding a herd of 255 dead zebra around a waterhole which had been poisoned by poachers.

His picture of his trademark African elephant bull, facing the viewer head-on with ears spread wide, Wise Old Elephant, was reproduced as a print by Boots the Chemist in 1962, and became a bestseller. That year, he held his first solo exhibition in London, and from there his paintings brought him world renown and wealth.

He may not always have found favour with critics, but the public at large loved his paintings, which were often mistaken for photographs because of the clarity and accuracy of his brushstrokes.

Portraits of the powerful and famous were also painted, including that of Zambian president Kenneth Kaunda in 1967, and of the Queen Mother two years later.

David’s conservation success was the subject of a 1970 BBC documentary The Man Who Loves Giants, also the title of his autobiography which was published six years later.

He raised more than £8 million for wildlife conservation, at first donating painting sales proceeds to charities such as the World Wildlife Fund. In 1984, he set up his own charity, the David Shepherd Wildlife Foundation, which campaigns to protect endangered species, and fight poaching and its trade. “What more could an artist wish for but to repay my debt to the animals I painted,” he said.

For his work in conservation, he received an OBE in 1980 and a CBE in 2008.

David took to social media to launch a 2011 campaign to save the tiger in the wild, under the banner of TigerTime. He said: “Man is the most stupid, arrogant and dangerous animal on earth. Every hour we destroy a species to extinction, and unless we start doing something about that very quickly, we are going to self-destruct.”

He hated hunting in any form. When I met him at his West Sussex home in 2004, he told me he would never have a domestic cat as a pet because of the potential damage to bird life.

David also raised money for the RAF Benevolent Fund and for the Bomber Command memorial in London’s Green Park, London.

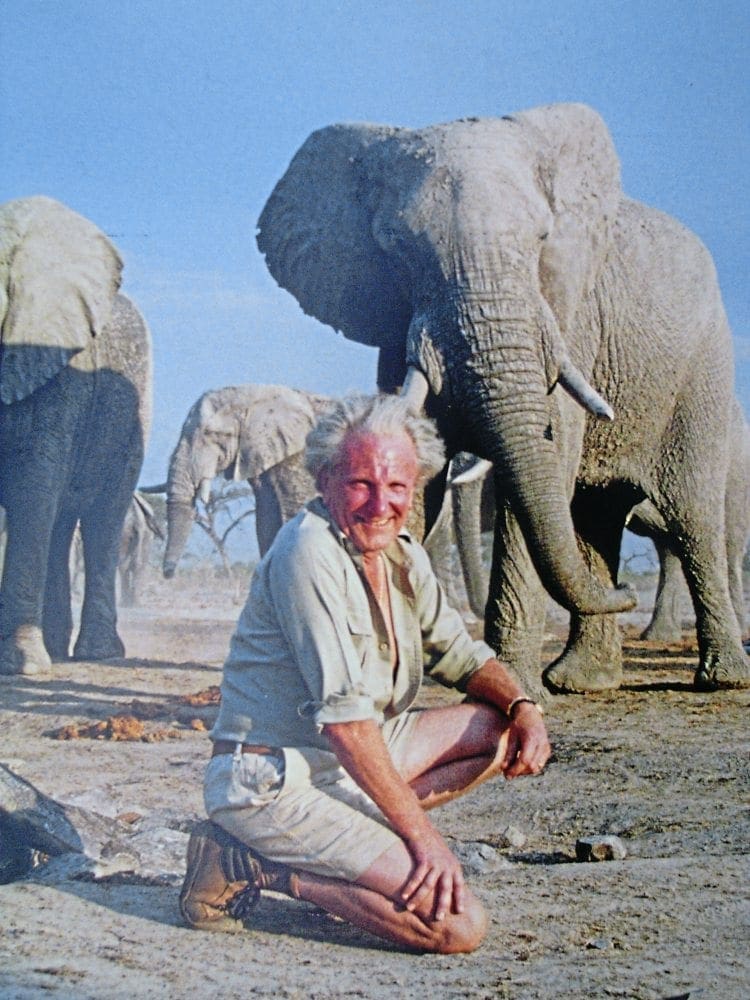

In 1967, he bought two steam locomotives direct from BR service, using the proceeds from a sell-out exhibition of his early wildlife paintings in New York to buy not one but two engines – firstly 1954-built BR Standard 4MT 4-6-0 No. 75029, which he later named The Green Knight, and 9F 2-10-0 No. 92203, to which he gave the heritage era name

Black Prince.

Outshopped from Swindon on April 6, 1959, it worked the last steam-hauled iron ore train out of Bidston Dock, Birkenhead to Shotwick Shotton steelworks, in November 1967.

The pair cost him £5000 and were initially based at the Longmoor Military Railway.

He once said: “The steam engine is valuable to us because it represents a more romantic time, one which contrasts with the age in which we are now.

“Progress? It is a poisonous word that involves everything that has become cheap and tacky.”

Saw the Cranmore potential

In November 1971, David first visited derelict Cranmore station on the GWR Cheddar Valley line that had been closed by Beeching, and saw the potential to create a heritage railway on which to base his two locomotives.

When the Longmoor Military Railway closed, No. 92203 was moved to Eastleigh depot and then, in 1973, to Cranmore, headquarters of the nascent East Somerset Railway, where it was based until 1998.

In September 1982, No. 92203 hauled the heaviest freight train in Britain at 2198 tonnes, at nearby Foster Yeoman Torr Works. Overhauled at the Gloucestershire Warwickshire Railway in 2004, it worked there until 2011. It then moved to the North Norfolk Railway and re-entered service there in 2014 after receiving an overhaul. David sold it to that railway in 2015.

The Green Knight also moved to the ESR in 1973. In the late 1990s the engine was sold to finance Black Prince’s overhaul, and is now based on the North Yorkshire Moors Railway.

The ESR’s first public steam services were started in 1974 with brakevan rides outside the engine shed. But David realised that to be successful, a heritage railway had to provide all the amenities that the public would need.

He built a new engine shed and a station at Cranmore with a ticket office, gift shop and café. In 1985 the line was extended to its current terminus at Mendip Vale.

However, in the Nineties, David felt he should devote his time to his wildlife foundation. He explained that you can always build another steam engine but once they have gone you can’t make another tiger.

He returned to the line in June 2007 to open the new engine shed at Cranmore.

David was given two more locomotives, by President Kaunda.

In 1974, he donated a helicopter to Zambia to help the local population hunt for poachers. In return, Dr Kaunda donated Sharp Stewart wood-burning former South African Railways Class 7A 4-8-0 No. 993 to David, along with a coach. The 1896-built 3ft 6in gauge locomotive had seen latter-day use at the Zambezi Sawmills Railways.

David brought No. 993 back to Britain and displayed it at Whipsnade Zoo, then the East Somerset Railway, and then the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum in Bristol, before being transferred to the Locomotion museum at Shildon. He later gave the locomotive and coach to the National Railway Museum. In 1976 had been the subject of another BBC documentary, Last Train to Mulobezi.

A second locomotive given to him by Dr Kaunda, ex-SAR 10th class Pacific No. 156 Princess of Mulobezi is kept at the Railway Museum, Livingstone where it has been restored to working order.

Built by the North British Locomotive Company in the early Twenties, Princess of Mulobezi also originally hauled timber for Zambezi Sawmills. It was saved from the scrapyard in the Seventies by David and operated on the Zimbabwean side of Victoria Falls for many years.

In 1991, South African rail transport company Spoornet, now known as Transnet Freight Rail, presented him with 15F 4-8-2 No. 3052, an example of the most numerous steam locomotive class in SAR service in exchange for a painting, and he named it Avril after his wife. It is stored at Sandstone Estates in Ficksburg.

He was an honorary member of the Bulleid Society and named No. 21C123 Blackmoor Vale at the Bluebell Railway in May 1976 and, after overhaul, again on August 19, 2000. He returned in July 27 for a footplate ride.

David had further books published. A Brush With Steam, a volume illustrating his love for steam locomotives, appeared in 1984, followed the next year by The Man and his Paintings, which covered the entire spectrum of David’s work. An Artist in Conservation and My Painting Life and Only One World were published in 1995. Painting with David Shepherd, Unique Studio Secrets Revealed came out in 2004.

Besides Africa, he classed Guildford shed as being one of his favourite places, and prints of his paintings of the last days of steam at Nine Elms adorn many enthusiasts’ walls.

North Norfolk Railway chairman Julian Birley said: “It is the end of an era. A great man who will forever be credited as one of this country’s greatest pioneers of railway preservation. And in so doing brought pleasure to hundreds of thousands of people.

“David first brought his beloved Black Prince to Norfolk over 10 years ago. He loved the railway and the staff and volunteers loved him.

“The arrival of Black Prince was a turning point in the railway’s fortunes. With David’s support and the immense popularity of both him and the engine, visitors came from all over the country to see them.

“Our thoughts are with David’s wife Avril, their four daughters and all their families.”

A statement from the ESR said: “We are all extremely sad to hear of the death of David Shepherd.

“From his first visit to Cranmore in 1971, to the grand opening of the East Somerset Railway in 1975, David has been integral to our growth into the friendly steam railway we are today. RIP David.”

His legacy

ESR chairman Richard Masters added: “He will not be forgotten at Cranmore and his legacy to us is the delightful railway that nestles in the Mendip hills and that is continuing to fulfil the dream of its creator.”

A statement from the David Shepherd Wildlife Foundation said: “For over 50 years David has dedicated his life to protecting some of the world’s most iconic and endangered animals.

“Using his talent as an artist to generate funds for their protection he inspired hundreds of others to follow and, in 1984, established his own wildlife foundation to give something back to the animals that had given him so much success as an artist.

“David lived with his wife Avril in West Sussex, and continued to paint every day until his recent illness.

“His extraordinary passion for conservation is continued by his four daughters, nine grandchildren, and great grand-daughter.”

A book of condolences was opened at the foundation office reception in Shalford, Guildford.

Read more News and Features in Heritage Railway – on sale now!

Archive enquiries to: Jane Skayman on 01507 529423 – [email protected]