In the early 1960’s Britain’s railway network was a third larger than it is today and seemingly stuck in the past. An attempt to ‘modernise’ which had started in the 1950’s had left the network with a fleet of new, and often unreliable locomotives, and truculent staff (and too many of them) just at the point where the balance sheet slipped into the red.

For the first time UK government had to do more than regulate, it had to decide what to do with the railways, which some regarded as a failing industry, based on outmoded technology.This was the start of the motorway era, speeding up traffic, with a boom in car ownership. Even those without access to a car could enjoy ‘express’ coach services on some routes, direct competition for the express train network that by 1966 had gained the title of ‘Inter-City’.

On the freight side more and more companies were moving freight onto the roads as lorry speeds improved, with door to door shipping often much quicker than by rail (and without the risk that consignments would get lost ‘in transit’). Then there was the threat from domestic airlines and the potential (seen at that time) for ‘short take-off and landing’ which would allow a much more comprehensive network of UK internal flights.

From the history of steam through to 21st century rail transport news, we have titles that cater for all rail enthusiasts. Covering diesels, modelling, steam and modern railways, check out our range of magazines and fantastic subscription offers.

Despite these threats to the railway’s ‘traditional’ traffic, and the whisperings of ‘futurologists’, many people both in the industry and outside it saw the railways as an essential part of the fabric of Britain. Fortunately, the railway had a research centre in Derby that would turn out to be the most significant railway research laboratory and in May 1964 a new state of the art ‘Engineering Research’ building was opened by Prince Philip.

The facility at Derby’s job was to improve as many aspects of the rail industry as it could, from better batteries to remote control of trains, and one of its tasks was to find out how to speed up freight trains.

The problem with freight, (indeed, it had long been seen as a problem) was that the UK rail network had thousands and thousands of short wheelbase wagons, which were prone to derailment at what would be considered a normal speed on the road. Freight trains in general moved slowly.

Adding to the transit time was the fact that the rail freight system was built around vast marshalling yards spread around the country. These took wagons from local sidings and shunted them into trains, which then went forward to the yard nearest to the geographical location the freight was aiming for.

After that wagons were ‘tripped’ to a factory siding or local depot for unloading, or transhipped to a railway road vehicle for final delivery. All of this took time. If British Rail was to stick to wagonload freight the distribution system seemed to be a given, so could you speed up the trains without them derailing?

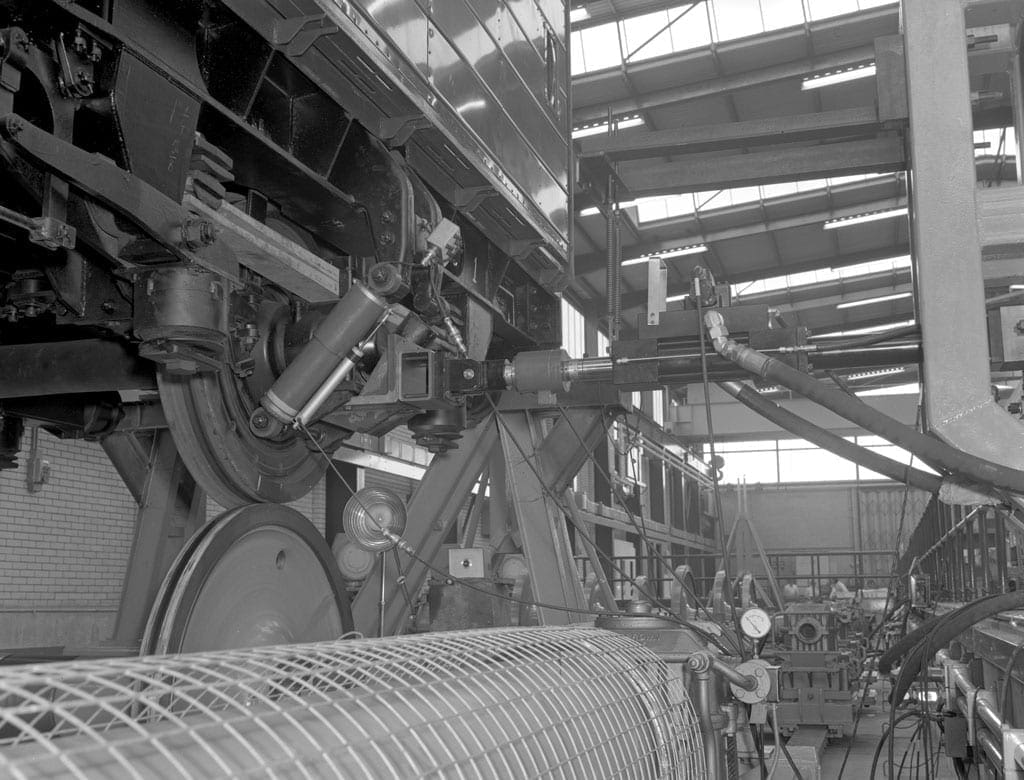

BR Derby Research started to look into the problem of wagon derailments in their new laboratory, first with a 1/5th scale model railway wagon and by 1965 on a full-scale roller rig using a modified rail van chassis.

They soon discovered that for a wagon not to derail at speed its movement relative to the track needed to be controlled in both the vertical and horizontal plane, with careful calculation (computers were used) as to how much control was needed. This was a decisive move away from the Victorian approach to a wagon underframe, which just used leaf springs and a lot of grease.

Very quickly HSFV1 (High Speed Freight Vehicle 1) was safe up to 140 mph on the rollers, and tested at up to 100 mph on the line. HSFV1 research actually had implications far beyond the world of slow-moving freight trains.

For the first time the fundamental relationship between the wheel and the rail was understood, something that would benefit railways worldwide, as it enabled high speed to be delivered safely, so long as you followed the research.

The work on the HSFV wagons (there were 6 variants) would lead to the MK3 bogie that gave the High-Speed Train (introduced in 1976) a smooth and safe ride. It helped improve the West Coast main line electrics which had been pounding the tracks to Liverpool and Manchester since 1967 with a new (and track friendly) AL6 ‘Flexicoil’ bogie. It also meant that a very high-speed train (capable of 150 mph) was possible, a train capable of seeing off the potential threat of a ‘short take-off and landing’ airline network.

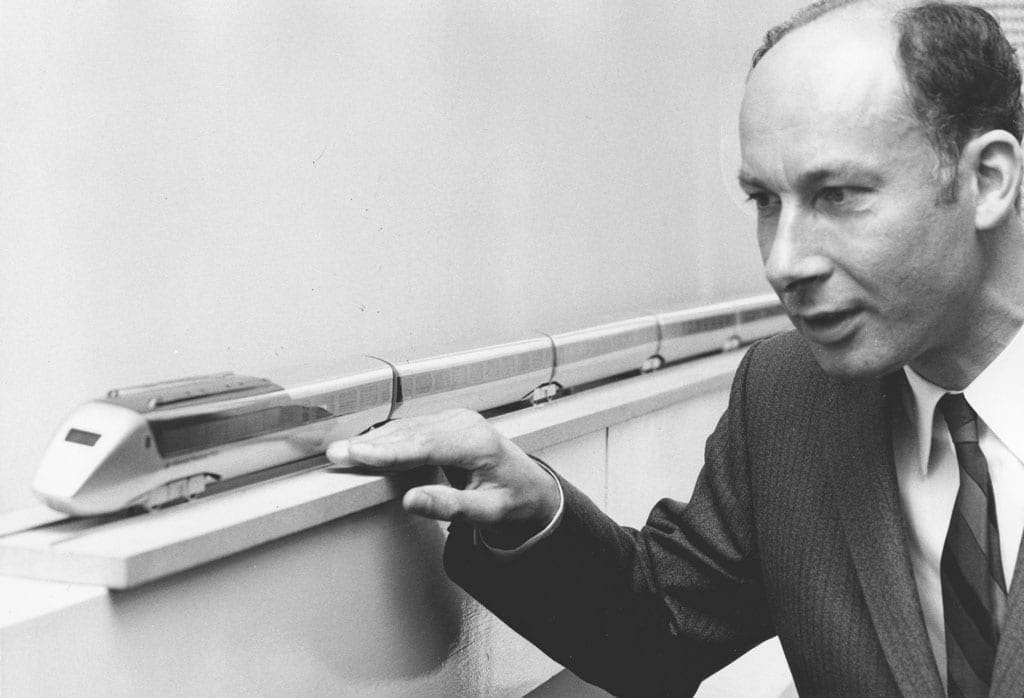

By 1972 the ‘Advanced Passenger Train’ was born and by 1973 it had moved from the scientists at Derby to the engineers running the network to be transformed into a train ready for passengers.

This led some of the team at Derby to look into whether there was an application for the HSFV research outside of the freight sphere, where a declining market share had made managers think twice about using the full sophistication of the HSFV underframe.

If a lightweight low-cost four-wheel chassis could travel at speed safely, as proven by the High Speed Freight vehicle tests, could this form the basis of a lightweight railcar or even a new form of carriage?

This was at a time when the need to replace the ‘modernisation’ plan diesel railcars from the 1950’s, then ubiquitous on BR, was becoming ever more pressing. This was particularly true on lines that had escaped the ‘Beeching Axe’ and which were now being kept open thanks to direct grants from government.

Whilst a new conventional Diesel Unit was seen as essential and would eventually see the light as the ‘Sprinter’, a low-cost alternative for lightly used rural routes (and suburban routes losing traffic to the roads) would also be helpful whilst the government made up its mind as to what size of network it was prepared to support. Hence the idea to marry a HSFV underframe with a Leyland ‘National’ bus body. The bus body had ‘exceptional strength and simplicity, well suited to a rail environment’ according to a government report at the time.

The Leyland ‘National’ was being made at a purpose-built factory at Workington, which had opened in 1971, and was supplying the nationalised ‘National Bus Company’ amongst others. British Leyland had been nationalised in 1975, meaning that this new train would effectively be a collaboration between three state entities all of which were on the ‘problem’ list.

The project’s potential to widen the market for the Leyland ‘National’ bus body must have seemed a godsend. BR was in the red, and Leyland’s bus division was sliding into the red, and this at a time when British Leyland and British Rail were often the subject of headlines with lots of potential ‘blow back’ to government.

Tests started in 1978 of a basic Leyland ‘National’ bodyshell on an underframe derived from the HSFV programme. A powered railbus – ‘LEV1’ (for ‘Leyland Experimental Vehicle’ no. 1, now part of the National Collection) came out a year later. A two-car version ‘class 140’ (one is now preserved) appeared in Jan. 1981. The programme also included four more single railcars – the design stretched and widened, which were demonstrated in countries as far apart as Denmark and the USA (orders were not forthcoming).

In the middle of the ‘Pacer’ development period the Conservative party was elected to government and committed to privatisation and shrinking the state; driven by the idea that ‘the market must decide’. (PM Margaret Thatcher is also reported to have once said to the BR Board ‘If any of you were any good you wouldn’t be here’). Hence, in the early 1980’s rail closures seemed never far away, with some rural routes being discussed for ‘bustitution’ (buses replacing railcars).

Getting inward investment from government for infrastructure improvements or replacement rolling stock was not easy. The ‘Pacer’, a cheap ‘stop gap’ product that propped up two ‘failing’ industries very much fitted the times.

It is worth remembering that in the decade the ‘Pacer’ was new, British Rail was arguing for more electrification, yet planning to close the electrified Sheffield – Manchester main line over ‘Woodhead’. (The line closed in 1981, possibly a ‘sacrificial lamb’ to encourage investment in electrification out of St Pancras).

1981 also saw BR need an additional £110 million of grant funding on top of the £644 million of funding agreed. The following year the Serpell report into railway finances came out and included the outline of a ‘profitable’ core network – ‘option A’, 84% smaller than what then existed.

Soon after this a headline scheme to close London Marylebone and turn it into a replacement for the London Victoria coach station by closing the route in from Northolt Junction appeared, only finally killed off in 1986. (The obvious fault to the scheme i.e. in general railway formations are not wide enough or high enough to convert to roads, was obvious then. The problem being that at that time supporters of the ‘Railway Conversion League’ included people at the heart of government).

Whilst Marylebone was hitting the headlines another headline ‘closure’ process got underway, that of the Settle and Carlisle main line. This had had services run down over a long period of time and when closure notices were posted in 1984 they did not come as much of a surprise. It would be five years before closure was refused, after a long and drawn out process that included an attempt to find a private buyer for the line.

In the middle of all this the ‘Pacer’ programme got going with 20 production models sponsored by West Yorkshire Passenger Transport Executive. These narrow-bodied trains of two coaches were pretty much Leyland National bus bodies, complete with seats, on rails. They lasted in service to 1997 after which twelve were sold to Iran (where some remained in operation until 2005).

Meanwhile the single railcars which had followed ‘LEV1’ had pioneered a wider body than a normal bus body, though still based on the ‘Leyland National’ and this led to the Class 142 ‘Pacer’. The first of these entered service in 1985, being preserved as part of the National Collection in 2019. The 142 was followed by the class 143 ‘Pacer’ this time using a bus body supplied by private bus and coach manufacturer ‘Walter Alexander’ of Kilmarnock.

In 1986 a ‘Pacer’ gained its highest endorsement from government when Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher rode in one, not from Todmorden to Manchester, or Chester to Helsby, or even Morecambe to Leeds, but from North Westminster to Abbotsford near Vancouver, Canada. Pacer 142 049 had been shipped to ‘Expo 86’ to support the British export effort where it ran services three times a day. PM Mrs Thatcher, had arrived in Vancouver by Concorde, something of a contrast.

By then the ‘Pacers’ were proving very unreliable in service, the fault lying with the Leyland engine and transmission. In July 1987 Neville Hill depot near Leeds reported that 26 of its allocation of 57 class 142’s were out of service.

By Dec. 1988 the Association of Metropolitan Authorities who ran Pacers within the areas of their ‘passenger transport executives’ were threatening to sue BR over their poor performance. BR’s ‘Pacer’ partner – Leyland Bus had by then been ‘privatised’, first in a management buy-out for £4 million. (At the time the company was actually capitalised at £17.4 million. The buy-out price included £2.5million worth of DMU’s about to be invoiced to British Rail, and the writing off of £55 million worth of debt; this approach to state assets was typical of the period.)

1988 saw the company sold again, this time to Volvo Buses who thereby took on the warranty for the ‘Pacers’. This meant that Volvo had to pay when the Pacers got new engines and gearboxes from 1988 onwards.

The upgrade would be one of the things that gave the ‘Pacer’ their long life. The other was rail ‘privatisation’, a Conservative policy promise in 1992, delivered in 1994, and which again meant no consistent approach to rolling stock replacement. (The dearth in orders for new rolling stock is credited with killing off ABB at York in 1996, claimed at the time as the most sophisticated carriage works in Europe).

Despite the upheavals of rail privatization, new liveries and new uniforms, trains still needed to run, and the Pacers were now reliable (if eccentric in world terms) and available. This was despite their having poor passenger comfort and a notorious poor ride over railways with older, jointed track, where they would bounce along in a fashion which gave them their nickname – ‘Nodding Donkey’.

In large parts of the north (but never the South) they kept the trains moving, into and through the rail ‘privatisation’ period. This was particularly true when the franchise ‘Northern Rail’ came into being in 2004, based on a ‘no-growth’ prediction and with a fleet of over 100 ‘Pacers’.

However, by then complaints about their lack of comfort and lack of access for anyone but the fully ambulant, had begun to push the humble ‘Pacer’ up the political agenda. In addition the railways had gone through a very rapid growth spurt in terms of numbers travelling.

Commuters in the north using crowded Pacers began to be more and more vocal about the train’s short comings. Then in June 2014 Chancellor George Osborne, gave a speech outlining his vision of a ‘Northern Powerhouse’.

Given that the ‘Pacer’ operated mostly in the north, the train seemed symbolic of what needed to change. It therefore has had the rare distinction of having been host to a Prime Minister on an export drive and having a Chancellor of the Exchequer announce that it would be replaced, which Osborne did in 2014. However, it would take over 5 years before Pacer No. 142 001 would join the National Collection as a museum piece, a quirky and curiously very British symbol of a different era in politics, engineering and on the rails.

Words and Photo credit: National Railway Museum