In the last part of our mini-series looking back to events of 50 years ago, Fraser Pithie considers a tragic accident that took place in early January 1968 on a section of the West Coast Main Line.

It led to the first judicial and public inquiry into a railway accident since the Tay Bridge disaster of 1879. The consequences were to affect the progress of British Rail’s modernisation plans for several years afterwards, and proved to be a defining moment in level crossing use by motorists. Hixon was also a tragedy that could have been avoided.

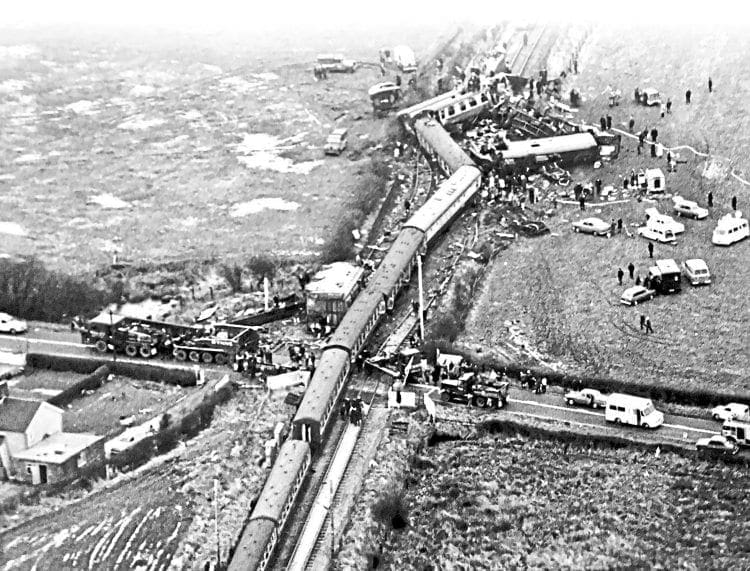

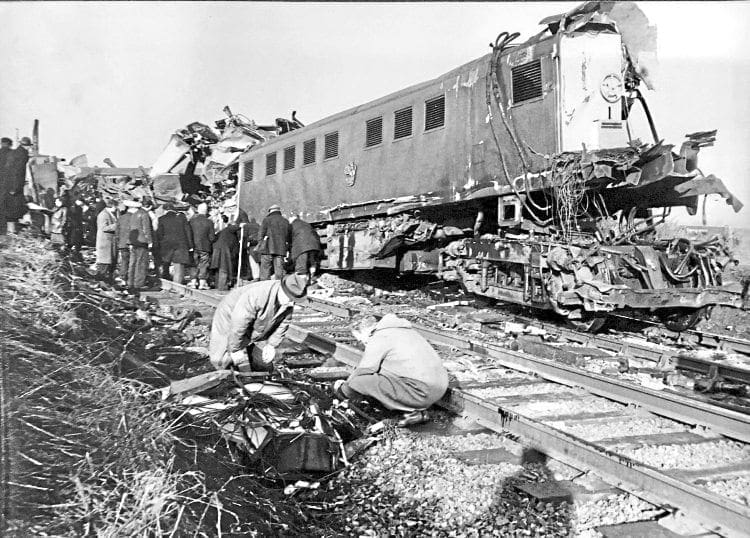

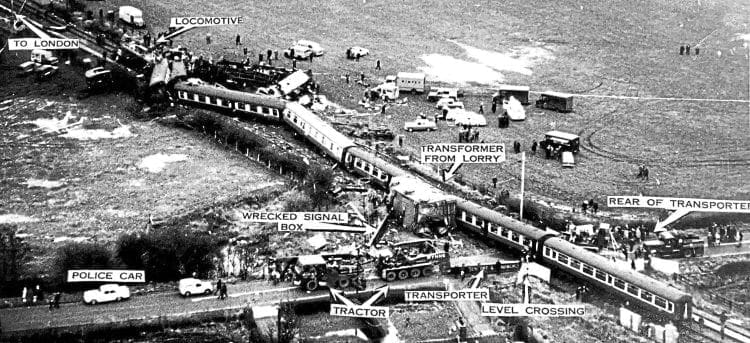

Often it is said that a picture is worth a thousand words, and in terms of several or more railway accidents, many images have fulfilled this maxim.

The dreadful events that took place near a disused airfield at a small hamlet known as Hixon in Staffordshire on Saturday, January 6, 1968 led to images that certainly conveyed the force and consequences of a high-speed rail/vehicle collision. This was irresistible force meeting a nearly immovable object.

As 1968 started, the modernisation of the railways, and in particular the West Coast Main Line (WCML), had advanced well. Electrification between London Euston, Rugby, Birmingham and Wolverhampton, along with the Trent Valley section of the WCML from Rugby to Stafford, was complete to the main destinations such as Manchester and Liverpool.

Further electrification from Weaver Junction, where the line to Liverpool diverges from the WCML, north to Preston, Carlisle and Glasgow was to follow and be completed by 1974.

A regular and fast express electric train service using a new ‘InterCity’ brand was launched in April 1966. It brought Manchester and Liverpool within three hours of London and was very much vaunted as the face of Britain’s ‘new modernised railway’. The trains were hauled by new electric locomotives, taking their power from a 25KV AC overhead system.

With the initial electrification of southern sections of the WCML also came other modernisation elements, and this involved crossings with roads, right of ways and farm tracks/accesses. A number of options were followed from closing such crossings, upgrading them or automating them.

Background

To understand and appreciate some of the elements that were associated and likely contributed to what became a tragic event in 1968, one needs to go back more than 170 years to the early days of railways in the UK.

In 1845, Parliament determined that strict rules would be applied to level crossings with railways and highways, tracks, rights of way etc. Initially, The Railway Clauses Consolidation Act 1845, (RCC), required that public level crossings be “manned and gated” with “good and sufficient” gates normally kept closed against the road, effectively fencing and securing the railway.

The RCC Act gave powers to the President of the Board of Trade to vary and reverse this practice, a power that was transferred to the Ministry of Transport in 1919. Over the period from inception of the Act up to and beyond 1919, such powers were increasingly exercised where the volume of road traffic increased and exceeded the volume of rail traffic on a level crossing.

Most, and certainly major, level crossings required that the gates were interlocked with signals ensuring a train could only proceed after receiving a clear indication, which was only possible once the crossing gates had been closed against the road.

With the passage of time, the Ministry of Transport made judgments to vary more crossings. However, this included some crossings, mostly that were not busy, to be changed without the protection of interlocking and signals. In 1966 there were some 2,500 public level crossings with 514 gated crossings NOT protected by interlocking and signals.

Of course, these gated crossings had to be operated by a crossing-keeper or signalman. This usually involved a laborious routine that spelt delays for road traffic as the keeper or signalman effected the closure of the gates and then the release/operation of railway signals to enable an approaching train to proceed.

It was commonplace that such delays could last as long as eight minutes. By the early Fifties the nature of transportation across Britain had changed out of all recognition from the early days that went back to the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, yet the legislation remained largely unchanged.

Eventually, an exception was made in 1954 and included in the British Transport Commission Act, which gave the Minister of Transport power to allow the use of lifting barriers at manned level crossings instead of gates.

By the mid-1950s the manning of so many level crossings had become uneconomic for British Railways, which by that time was facing considerable competition from road hauliers and losing business. Moreover, it was also becoming difficult to attract and employ personnel to undertake crossing-keeper roles.

In 1956 a working party was set up between the Ministry of Transport, HM Railway Inspectorate (HMRI) and British Railways to examine continental methods for protection of level crossings. They visited and considered how France, Belgium and Holland were dealing with a similar problem.

HMRI, which was effectively an arm of the Ministry of Transport, took the lead role, although traditionally it had confined its activities to investigating railway accidents. HMRI’s personnel at the time had no experience of implementing or managing operational systems or infrastructure on the railway.

The British Transport Commission promoted a clause in the Transport Commission Bill of 1957 that would “permit the installation of automatic crossings instead of gated crossings”. The Bill was enacted into law and Section 66 of British Transport Act 1957 paved the way for the installation of automatic level crossings.

Most of these were of a half-barrier design with warning lights and a bell and were known as automatic half barriers (AHB). Despite such enabling legislation, caution was initially exercised in pursuing AHB introduction.

Only a handful of crossings were converted. A number of criteria were applied that effectively confined the use of AHBs to all but the very quietest of crossings in terms of road vehicle usage. The initial AHB installations were developed jointly by British Railways, the Civil Aviation Authority and Ministry of Transport/HMRI.

Between 1957 and 1963 further analysis was done on automatic crossings in other countries, including the United States, Canada, and with parts of Europe also revisited. The widespread introduction of automatic level crossings had moved apace in these other countries.

Someone from HMRI who had been very much involved in the AHB evaluation and examination of the automatic crossings was Colonel Denis McMullen, and he had stated in 1957: “If automatic half barriers are to be adopted, the principle must be recognised that it is the responsibility of the individual to protect himself from the hazards of the railway in the same way as from the hazards of the road.”

In 1963 Colonel McMullen became chief inspector of HMRI.

In 1961, another Inspector from HMRI, Colonel W P Reed, was put in charge of the AHB evaluation/implementation work. He soon applied considerable enterprise in pushing ahead with AHB introduction as much as possible. Indeed, the HMRI’s involvement went further; Colonel Reed was charged with approving and ‘signing off’ each new AHB.

Reed pressed for and obtained legislation to permit the installation of AHBs with no need for telephones or signal protection in 1963. This approach was viewed with considerable scepticism by some BR operational managers who, in many cases, found ways to ensure a phone was nevertheless provided at AHB crossings.

Colonel Reed tried to put a stop to what he likely considered was insubordination by seeking and obtaining further legislation in 1966 that bolstered AHBs being installed without the need for a telephone.

The scene was set for a faster railway with fewer stops, and due to Dr Beeching’s rationalisation, a railway where maximum speeds could be raised and crucially maintained for prolonged periods by removing signalling and manually operated level crossings. Colonel Reed saw a prize for helping deliver Britain’s new fast railway through what he increasingly saw as his AHB project.

Abnormal load

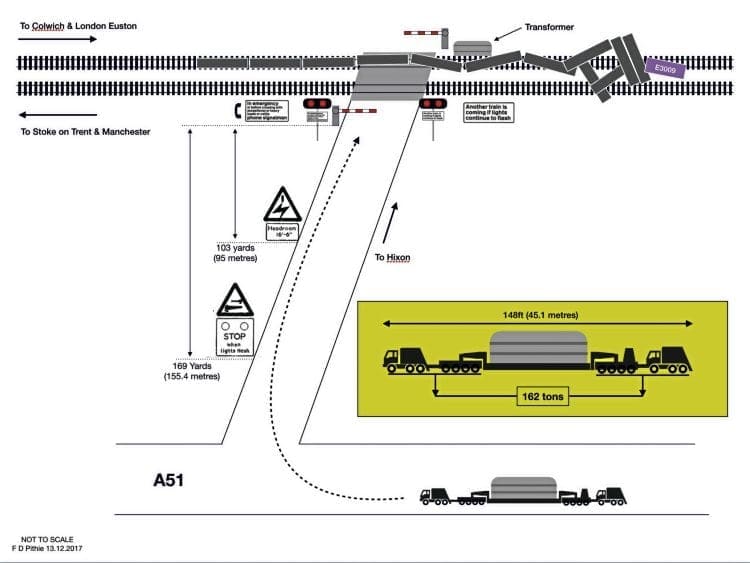

A level crossing on a minor road leading to a disused airfield existed at Hixon in Staffordshire where it crossed the Manchester to Stoke-on-Trent and London section of the WCML, three miles north of Colwich Junction.

The crossing, which had been operated by a traditional manual signalbox until April 1967, was converted to a new AHB crossing with responsibility transferred to Colwich Junction signalbox. The new AHB was operated by a system that was duplicated.

Approaching trains ‘struck in’ a treadle at 1,004 yards (918 metres) from the AHB crossing and the occupation of the relevant track circuit also initiated the AHB. The maximum line speed at Hixon was 85mph. This meant there were just 24 seconds between the fastest train on the line operating the treadle and the train reaching the crossing.

The disused airfield at Hixon was used as a storage facility for the English Electric Company (EE). Large equipment concerned with high voltage electrical infrastructure, such as transformers, was regularly stored at the location and transported to and from the site by road using heavy haulage equipment.

Much of the electrical equipment came from EE’s works in nearby Stafford. It had become a fairly regular activity with several previous trips between the two locations. On January 6, 1968, a 120-ton electrical transformer was to be taken from EE at Stafford for storage at Hixon.

In 1968 the movement by road of any load that exceeded either 90ft length, 20ft width, or a total weight of 150 tons was subject to the Motor Vehicles (Authorisation of Special Types) General Order of 1966, which was a statutory instrument of the then Road Traffic Act of 1960.

The planned route, agreed and approved by the Ministry of Transport, took the abnormal load along the A51 trunk road until it turned off down a minor road towards Hixon airfield. Along this road, the load would cross the WCML.

That January day was a normal Saturday morning and at Manchester Piccadilly the 11.30am express to London Euston with its train description of 1A41 prepared to leave on its journey south. The express would be hauled by electric locomotive No. E3009.

The locomotive was one of 23 locomotives built primarily for passenger use from a total build of 25 and given the designation of ‘AL1’ (later Class 81). Producing some 48,000lb of tractive effort, the Bo-Bo locomotive, with its 12-coach train, weighed 491 tons.

Earlier on the same morning, a journey had begun involving an abnormal load weighing a total of 162 tons, consisting of a large electrical transformer on a low loader belonging to Wynns Haulage Ltd. The load was to follow a circuitous route, covering some seven miles from EE’s works at Stafford to Hixon, with the movement having an escort from Staffordshire police.

The planned route took the abnormal load along the A51 until it reached Station Road (subsequently renamed New Road), which was a minor road into which it would turn off heading towards Hixon airfield. Just after midday, the abnormal load turned off the A51, and nearing its destination, proceeded along a very straight Station Road, where two triangular warning road signs on the left-hand verge of the carriageway came into view

One sign was a new type that showed an image similar to ‘two hammers’. There was an information plate on the sign stating, ‘STOP when lights show’. A further sign was some 60 metres along from the first and was also relatively new, showing an ‘electrical flash’ symbol with an information sign stating, headroom 16ft 6in. These were the new warning signs for the AHB crossings.

As the transporter approached the crossing at around 4mph, the police escort cleared the crossing and drove on forward by about some 70 yards (64metres). The transporter slowed to 2mph before starting its journey over the level crossing. This allowed three of the Wynns’ crew to walk alongside the abnormal load and observe the clearances between the ground, overhead wires and transformer.

The Manchester Piccadilly to London Euston express, 1A41, was crewed by driver J A Atkinson and fireman Hockenhall from Manchester (Longsight) to Stoke-on-Trent, where they were relieved by Euston men – driver Stanley Turner and fireman Toghill.

Atkinson remained on the footplate south of Stoke, while Hockenhall retreated to the ‘cushions’. Both Longsight men were due to travel to Euston to take up a booked return working. Between Stoke and Colwich Junction, travelling at 85mph, and with Turner, Toghill and Atkinson all in the front cab, 1A41 approached Hixon level crossing.

Part of the new AHB signage was a sign at the crossing that stated: “In an emergency or before crossing with exceptional or heavy loads or cattle phone signalman.” Despite the fact the transporter represented both an exceptional and heavy load, no one telephoned the Colwich signalman and the transporter moved forwards onto the crossing.

The front tractor unit had cleared the crossing with the main bulk of the load straddled across both railway lines when the lights and bells of the AHB operated. This was followed within six to eight seconds by the barriers descending onto the trailer and transformer. The Wynns’ crew were aghast, the rear bogie of the trailer was still about two yards (1.8 metres) short of the barrier on the A51 side of the crossing and they realised a train must be coming.

Hopeless

The train had ‘struck in’ the automatic treadle designed to operate the Hixon AHB, and the Manchester to Euston express was on a falling gradient of 1-in-600, bearing down on the crossing. At 85mph, it would take the train about 24 seconds to reach the crossing from striking the treadle.

After the barriers had finished coming down there was around just nine seconds before the express would reach the crossing. Two of Wynns’ crew desperately tried to get the abnormal load clear of the crossing, but unknown to them at that time the situation was hopeless.

Nevertheless, Mr B Groves, at the front of the transporter, who could now see the train approaching on his left, shouted and warned the crew to get clear and then tried to accelerate the transporter off the crossing. At the rear was Mr A Illsley, who also tried to assist Groves’ efforts by accelerating from the rear tractor unit, despite by doing so meaning it would bring him into the path of the train with potentially fatal consequences.

On the footplate of No. E3009, Hixon crossing was now in full view with the transporter prostrate across its length. Driver Turner made a full emergency brake application, but the situation for the train was also hopeless.

Allowing for some speed reduction through braking at around 75mph, a distance of around 1,500 yards was needed to stop. Only 400 or so yards was all that now existed between the train and the 162-ton transporter, a distance that would close in little more than a few seconds. A collision was now inevitable.

The valiant efforts by Groves and Illsley did manage to move the transporter far enough to avoid a complete head-on impact with the electric transformer itself. The locomotive hit the last two or so yards of the transformer and sheared the rear swan neck off between the trailer and the rear bogie of the transporter.

The collision and impact were catastrophic. Illsley described what must have been a dreadful experience for him of seeing driver Turner “crouched over the controls staring fixedly ahead of him”.

Driver Turner, Atkinson and Toghill, all of whom were on the footplate of the loco, lost their lives – it must be assumed instantly, as the front of the Class 81 locomotive was completely destroyed.

The transformer was sheared off the transporter, thrown to the left and pushed up the line as the first five coaches of the Euston-bound express were wrecked, with the following three coaches derailed. Both running lines were ripped up for a distance of about 126 yards (110 metres).

The impact of the collision had driven the leading bogie of No. E3009 back under the locomotive body, shearing the centre pivot casting bolts and leaving the centre pivot out of its housing in the main underframe. All four side bearer suspensions had gone, but the bogie had remained under the locomotive throughout the subsequent derailment until it came to rest 117 yards (107 metres) from the point of impact.

One of the police constables in the escort vehicle immediately radioed Staffordshire police HQ at Stone. This was a critical action as getting through so quickly to HQ enabled all the emergency services to mobilise to the accident scene quickly. Doctors attended casualties at the scene, arriving in army helicopters.

Protection

At Colwich signalbox, no fewer than eight track circuits lit up on the signalling panel. Simultaneously, power failure alarms for the 25kv overhead system activated together with an indication of AHB failure at Hixon.

The signalman, Mr B Regester, set his covering signals all to danger and rang control at Stoke. Meanwhile, at Meaford signalbox, 12 miles north of Hixon, signalman Woodcock had noticed 1A41, that had passed him on time, was still showing in the section before Colwich.

This led to Mr Woodcock trying to contact Colwich, but he could not get through. Sensing something was wrong he took no chances and immediately placed all his signals at danger and contacted Stoke-on-Trent Power signalbox.

A further call to a lineman’s office at Stafford led to a technician travelling immediately to the scene of the accident and removing the fuses in the signals near the crossing. This action effectively set distant signals to danger and thus afforded more protection to the accident scene.

The severity and catastrophic nature of such an accident like that at Hixon can often lead to other elements related to such an event being overlooked.

Consequently, it’s important to note the public inquiry saw fit to commend the actions of the guard of the Manchester to Euston express, Mr W C Final. Immediately, as a result of the accident, Mr Final ran north along the line to set detonators at the appropriate points, and upon reaching a telephone contacted electrical control at Crewe to inform them what had happened.

Incredibly, Final then ran south back to the site of the wrecked express and for a further mile, having to negotiate uneven fields to get past the train wreckage, so he could set detonators at points south of the accident. In all, and at the age of 49 years, he ran more than four miles to carry out his duties in what must be recognised as being in the best tradition of the railways.

Mr Hockenhull, the Longsight fireman who was on the cushions, got a lift in a van to a house with a telephone from where he made an emergency call.

Back at the scene of the accident 11 people had lost their lives, with 41 others requiring recovery to hospital and treatment. The first of the injured arrived at Stafford General Hospital at 1.05pm, with most joining them by 1.35pm. The last deceased passenger was recovered at 4.50pm and finally, driver Turner’s body was recovered from the wreckage at 11.10pm.

The abnormal load needed to have been travelling at 6mph to get over and clear the level crossing within 24 seconds. At the 2mph estimated at the subsequent inquiry as the speed that the load proceeded over the crossing, at least 60 seconds would have been required.

A basic approximation, using assumptions with data from the accident inquiry, suggests the collision between the Manchester to London express and the low loader and transformer expended around some 280 megajoules of energy. That’s roughly equivalent to the energy of four Class 47 locomotives (117 tons each) hitting a solid object at 75mph.

Inquiry

The Minister of Transport Barbara Castle determined a public inquiry would be held not only into the events and circumstances of the accident at Hixon, but consider more widely the issue of AHBs and their safety. Consequently, the usual traditional investigation by HM Railway Inspectorate would not take place because HMRI had been, and continued to be, involved in the design, implementation and installation of AHBs.

The public inquiry was chaired by a barrister, Edward Brian Gibbens QC. In 1967, Gibbens had been counsel for the National Union of Mineworkers at the public inquiry into a disaster in October 1966 when a coal spoil heap slid down into the South Wales mining village of Aberfan, consuming the primary school and taking the lives of 116 children and 28 adults.

On Hixon, Gibbens concluded: “The real cause of the Hixon disaster was ignorance, born of lack of imagination and foresight at the sources one would expect to find them.” Few were spared from criticism largely because in different ways most organisations and/or certain individuals within them had all played a part in creating what was an inherently unsafe situation.

However, and importantly, Gibbens prefixed his criticisms with a clear caveat. He described those who were actually involved at Hixon as “actors” who “were mainly victims of the shortcomings at more responsible levels”. He was certainly right in holding that contention, but he did not know just how right he was, because while apportioning blame across the board he largely missed the ‘elephant in the room’ – HM Railway Inspectorate.

As part of the proceedings the inquiry learnt of a ‘near miss’ with many similarities to the Hixon collision which had taken place 14 months before on the Western Region and coincidentally also involved a Wynns’ transporter.

At Leominster, on November 8, 1966 a Scammell low-loader carrying a 15-ton crane was driven over a recently installed AHB by James Horton. The road surface on the far side of the crossing had not been fully made up with a four inch (10cm) drop remaining. As the tractor unit reached the far side of the crossing the tractor unit went over the drop causing it to ground the low loader and block the lines.

A railwayman, believed to be a signalman from the nearby station according to the inquiry report, told Horton a train was approaching and it was too late to stop it. Consequently, Horton violently accelerated the Scammell tractor unit and slipping the clutch, he managed to get the front to jump upwards and drag it clear from the rail.

He cleared the line as the train sped past behind within inches of the low loader. The event at Leominster had been too close for comfort and Horton believed these ‘new crossings’ did not provide even enough time for a driver to push a stalled car off a crossing. Consequently, he decided to report the near miss to his employer, who supported his concerns and wrote to the chief civil engineer of BR Western Region.

The letter set out the events at Leominster and went on to express concern at the fact that as trains operated the warning lights and automatic barriers, there were no means that could stop trains which were over the crossing within a few seconds.

The response from British Rail was breath-taking.

Edward Gibbens QC commented that the response, written by a Mr Lattimer, the assistant general manager of the Western Region, was “remarkable for its arrogance and lack of insight (on a par with the statement ‘You can’t park there’)”.

Gibbens’ comments were not surprising when one considers this extract from BR’s response to Wynns’ letter: “Had there been a serious accident, it would have been subject to a ministry inquiry and the principal point of the inquiry would not have been the safety of the crossing, which is an approved one, but why the vehicle was on the line when the train approached, and the barriers were about to close to road traffic”.

Gibbens scathed further about the BR reply: “It is most unfortunate that the writer did not point out the hazard to slowly moving vehicles and the requirement that the driver of any heavy or exceptional load must telephone the signalman before crossing, which was a precaution vital to the safety of automatic crossings.

“Had he done so, we can only speculate as to whether the accident at Hixon a year later would have happened: in all probability, it would not.”

As powerful as this event was in the light of the subsequent tragedy at Hixon, the reference to the Leominster event was a double-edged sword at the inquiry because it entrapped Wynns. By writing to BR they clearly had picked up on what they believed to be a significant risk to safety at the new crossings.

Wynns’ counsel admitted the company directors had now wished they had pursued the matter further with BR and not let the tone of the reply put them off.

It’s true that Wynns were culpable in so much as with the knowledge of the Leominster event they chose to take no action internally with employees to make them aware of the new automatic level crossings and the risks associated with them.

However, Gibbens took this much further stating the principal factor contributing to the Hixon disaster lay with the directors of Robert Wynn & Sons Ltd.

Having had the benefit of an earlier near-miss that they initially viewed as serious enough to write to BR about, they chose not to pursue matters upon receipt of what was an arrogant and indifferent response from BR. Wynns’ honesty at the inquiry backfired and entrapped them, while others at the inquiry were being far from fullsome with the facts

Staffordshire police

The Chief Constable of Staffordshire Police was not without criticism either. Gibbens cited that senior officers had not properly appraised the hazards arising from AHB crossings and had not extracted the relevant information from the MoT’s requirements and explanatory notes.

Gibbens commented: “I am satisfied that, with such information, the two constables escorting the load on the January 6 would have realised its significance and caused Mr Groves to telephone for permission to cross.”

British Railways

The lack of adequate publicity both locally and nationally together with unclear messages within that publicity which was issued was criticised. It was said BR had not appreciated the level of risk associated with the crossings and further had not given much thought at all to heavy and/or slow-moving vehicles traversing the crossings.

This even extended to the provision of telephones at the automatic crossings. This criticism was grossly unfair as BR was not in the driving seat with AHB installations, it was HMRI, and in particular Colonel Reed.

Ministry of Transport and HM Railway Inspectorate

The inquiry highlighted a number of elements where the ministry had come up short of that which should and could have been reasonably expected.

These failures were wide-ranging – from poorly designed and thus misunderstood road signs to abnormal load orders seemingly oblivious to AHB crossings and the risks associated with them. The installation of new AHBs had led to a new warning sign being developed and installed.

The triangular sign attempted to show two barriers, but to the untrained eye they appeared to be two hammers. This new sign, combined with very little experience by the public of AHB crossings in the UK at the time, meant most road users had little idea what the sign meant.

The inquiry was left in no doubt by an expert witness, Professor Colin Buchanan, who said the new sign was “ridiculous”.

Added to this was the sign at the crossing that ‘combined’ two messages. The message of ‘In an emergency’ appeared with ‘exceptional or heavy loads’. “There is hardly a rule in the book that this sign does not break” the inquiry was told.

A planned national TV campaign, using public information ‘fillers’ that ran between programmes on both BBC and ITV had run from 1965 until January 1967, when because of planned revisions to AHB crossings it was suspended. It would be October 1967 before TV devoted any further time to publicity about the growing number of new AHB crossings. Nearly a year was lost.

Additionally, Gibbens stated a decision in 1966 not to include cautions in special order routes, where such a route traversed an automatic crossing, was wrong.

Gibbens also concluded officials from the MoT and HMRI, having thought about slow moving vehicles in the context of AHB crossings, failed to realise the situation presented what he termed a “grave danger’. This last point was the closest Gibbens got to the ‘elephant in the room’.

Then another tragedy occurred.

For the Hixon Inquiry, which had not finished, a bad situation got considerably worse. Five people were killed at an AHB at Beckingham, Lincolnshire, when an EE Type 4 No. D252, hauling a York to Yarmouth express, hit an Austin A40 and pushed it along the railway line for a distance of 555 yards.

Immediately after the barriers had lifted following the passage of a down goods train the A40 tried to go over the crossing. As it made its way over the crossing the barrier lowered because of a second train (the York to Yarmouth express) approaching on the Up line.

Despite frantic attempts by the A40’s driver, a Mr Hilton, to push the car clear, it was hopeless for he had less than five seconds before the train was at the crossing, travelling around 60mph. Mr Hilton and his four passengers were killed.

The HMRI report blamed Mr Hilton’s Austin, describing it as “an old car in poor condition”. The report’s conclusion went on to say the accident happened under what was described as the “critical second train situation”. Nevertheless the report cited a defective starter on the A40 that meant the car couldn’t be restarted as the cause. Public and press reaction understandably become frenetic.

Ignorance

When one studies the inquiry, the evidence and the events, not just of January 1968, but for a few years before, what becomes apparent is that through the change with level crossings one key element that seems so obvious now, clearly had not been appreciated then.

The shift of responsibility for safety from the railways to the road user that AHB crossings meant was not appreciated by most people. The change hadn’t been managed to anywhere near the standard required. Consequently, a toxic mixture of arrogance, indifference, ignorance and sloth determined AHBs were unsafe. They were no longer accidents waiting to happen, because several already had.

Was it that some of those in HMRI were to a degree de-sensitised to small numbers of casualties or fatalities because they were used to accidents involving much higher numbers? Why did at least some people at HMRI seem unable to grasp what they were plainly missing when it came to the human cost of relentlessly pressing on with installing new crossings in the face of massive safety concerns?

Accountability

As has been shown on countless occasions before and after Hixon, the normal investigation held by HMRI following a railway accident quickly identified the issues, causes and provides solutions through recommendations.

Public inquiries, with their basis in English law, are an adversarial process that encourages, indeed expects, at least two or more ‘sides’ to put their accounts on any given issue. A traditional investigation by HMRI could not be carried out because it was also involved… as it turned out, to a significant extent.

There is a profound irony about this as the non-adversarial process used by a traditional investigation would have quickly understood the complete picture about Hixon, and more importantly, the AHB programme in general.

A traditional investigation would, as a matter of course, have followed from end-to-end, all issues that arose, including several that Gibbens, an accomplished barrister as he was, chose not to pursue.

Afterword

In late November 2017, retired teacher Richard Westwood published a book, The Hixon Disaster – The Inside Story (pictured below left). Richard’s father, Jack, was a signal and telecommunications technician for BR and was present at Leominster when the ‘near miss’

with the Wynns transporter took place on November 8, 1966.

Jack Westwood’s actions, although examined at the inquiry, were not mentioned in the inquiry’s written report. Those actions reveal he managed to make a telephone call to the signalman, who immediately threw the distant and home signals protecting the crossing at Leominster back to danger.

Although it appears the train may have passed the distant signal the train driver did see the home signal change to danger and applied the brakes.

The effect of this slowed the express passenger train before it reached the crossing and contributed, along with the brave actions of the Wynns’ driver, to the event being a ‘near miss’ rather than an accident with much worse and potentially fatal consequences.

Why might you ask, was Jack Westwood’s intervention not included in the inquiry report? Well, the clue is Jack Westwood was able to use a telephone to contact the signalman… a telephone that would not have been there if Colonel Reed from HMRI – when he sought to approve the new crossings – had had his way.

Reed largely saw telephones as unnecessary as he did protection of AHBs by signalling. AHBs to him were a necessity for a modern fast railway and little should be allowed to intervene in achieving the objective of trains being able to traverse crossings at maximum speed.

Thankfully, two things got in Reed’s way. One was British Rail, whose many operational managers’ instincts informed them that AHBs without telephones and signal protection were unsafe.

The second, in the case of Leominster’s AHB, was the National Farmers’ Union which, through one of its members, a local farmer called Bill Sparey, successfully argued at the initial site meeting for the provision of a telephone at Leominster crossing. It proved lifesaving.

Richard Westwood’s book is an intervention unique in nature. His understandable desire to learn more about his father Jack’s part in the event at Leominster is axiomatic to a much wider matter with national significance. His forensic examination of the Hixon disaster, the public inquiry papers, BRB, Ministry of Transport, and HMRI files makes for fascinating reading.

Westwood details a truly shocking set of affairs that, summarised, demonstrate a botched and ill-informed approach to the installation of AHBs, followed by a dreadful lack of transparency and even mendacity by some of those involved when it came to the subsequent public inquiry.

Some 50 years since the Hixon accident, Westwood’s investigations and his book are timely, and shine a new light not just on the tragic event at Hixon, but also other AHB events at Leominster, Yapton and Beckingham, the latter of which turned out to be fatal for a whole family.

The Hixon Railway Disaster – The Inside Story does not seek to cast blame or accuse, it simply suggests to the reader that “the facts speak for themselves”.

Having written most of this feature before obtaining a copy of the book, I would agree, having read it… the facts do indeed speak for themselves. I felt when researching the final feature for this mini-series that some of the elements were somewhat inexplicable; they are less so now. Consequently, I felt it necessary to add this afterword.

So, the principal factor contributing to the Hixon disaster? I don’t believe it was Wynns, as it was not responsible for the approach taken concerning the installation of AHBs.

At Hixon and Beckingham 16 lives were needlessly lost for nearly as many years of high-level indifference, arrogance and ignorance. The ‘elephant in the room’ that I referred to earlier is clear for all to see in Richard Westwood’s new book. This cautionary tale is required reading for anyone interested in the history of railway safety in this country.

It would be several years after Hixon and the public inquiry before more level crossings were automated. Today, the Rail Regulator does not permit the construction of any new level crossings, preferring clear guide separation and the elimination of risk.

The Railway Magazine Archive

Access to The Railway Magazine digital archive online, on your computer, tablet, and smartphone. The archive is now complete – with 123 years of back issues available, that’s 140,000 pages of your favourite rail news magazine.

The archive is available to subscribers of The Railway Magazine, and can be purchased as an add-on for just £24 per year. Existing subscribers should click the Add Archive button above, or call 01507 529529 – you will need your subscription details to hand. Follow @railwayarchive on Twitter.