The son of Marc Brunel and Sophia Kingdom Brunel, Isambard Kingdom Brunel was born on April 9, 1806 in Portsmouth.

Young Isambard was not only to follow in his father’s footsteps as one of the greatest engineers of his day, but with his big railway from London to Bristol, and the seaward ‘extension’ by which steamships would continue the journey to New York, would soon eclipse his fame.

The son of a wealthy farmer, Marc Brunel was born on April 25, 1769 in Hacqueville in northern France, and displayed a talent for drawing, mathematics and mechanics at a very early age, to the disdain of his father who wanted him to become a priest. Marc enlisted as a cadet on a French naval frigate, but on returning home in 1792, became appalled by the revolutionary excesses of the Jacobins.

From the history of steam through to 21st century rail transport news, we have titles that cater for all rail enthusiasts. Covering diesels, modelling, steam and modern railways, check out our range of magazines and fantastic subscription offers.

He fled to England to escape the vengeance of a revolutionary mob, and met Sophia, then 17, the youngest of 16 children of Portsmouth naval contractor William Kingdom. Marc Brunel subsequently made a fortune in the US, building the Bowery Theatre, an arsenal and a cannon foundry along with many other buildings in New York. However, in 1799, he returned to England, and married Sophia in the parish church of St Andrew in Holborn on November 1 that year.

His business took off big time when the British government adopted his scheme for mechanising the manufacture of pulley-blocks for ships, which until then had been made by hand. Marc was given a £17,000 contract, and the Brunels moved from their home in London to Portsea near Portsmouth so he could take charge of the project. He went on to design huge steam-powered machines for sawing and bending timber, as well as machines for stocking knitting, printing and the mass production of boots and shoes.

His achievements were publicly recognised in 1814 when he became elected to the Royal Society. Marc installed a log handling and sawmill at the naval dockyard in Chatham. Buying, storing and handling timber was at the time a major problem and expense for the navy, as a typical battleship needed 2000 mature oak trees, with much of the timber being imported from Russia. The wood had to be seasoned and stored.

Few saw any significance in what was a minor detail at the time, but the sawmill was served by a railway, with rails that were placed 7ft apart. While he was working at Chatham, Marc Brunel observed the marine shipworm Teredo navalis in action, boring through the toughest timbers. This worm was a curse on seafarers throughout the world, and was said to have sunk more ships than any enemy action.

The boring action of the shipworm gave Marc Brunel inspiration for a method of tunnelling through soft ground, and possibly beneath a river. However, despite his resourcefulness in the world of technology, Marc Brunel paid scant attention to his financial affairs.

A Russian influence…

In 1820, his bankers west bust, and in May 1821, Marc and Sophia were incarcerated in the King’s Bench debtors’ prison for three months – until the Duke of Wellington persuaded the government to pay £5000 to prevent his services being lost to Russia, where the tsar was keen on him building a river bridge.

Isambard attended boarding school in Hove, Sussex, and together he carried out a survey of the town. At 14, he was sent to the College of Caen in Normandy, and progressed from there to the Lycee Henri-Quatre in Paris.

Marc arranged for him to have an apprenticeship under world-famous clockmaker Abraham Louis Breguet.

Returning to England in August 1822, after his father’s financial troubles had subsided, Isambard set to work in his father’s office on yet more inventions, including two suspension bridges for the French government and the world’s first double-acting marine engine.

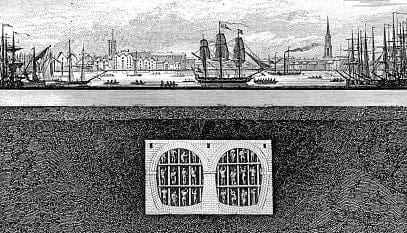

The father-and-son team laid claim to their place in history with the building of the Thames Tunnel, hailed in its day as the eighth wonder of the world. The growth of the port London in the wake of the opening of the first enclosed docks on the Isle of Dogs in 1802 led to warehouses mushrooming on both sides of the river, but there was no means of communicating between them other than by boat. Clearly a physical crossing downstream of London Bridge was needed, but one high enough to allow ships to pass below, like today’s Queen Elizabeth II Bridge on the M25, could not be built with the technology of the day.

It was said that the Assyrian queen Semiramis had a tunnel built beneath the River Euphrates at Babylon, and therefore a tunnel was a possibility. Mine workings in west Cornwall by then had extended beneath the seabed, so the legend was becoming not only a theory but a scientific possibility. In 1802, Robert Vazie and Richard Trevithick announced plans for a shorter tunnel on the comparatively short section of the river between Rotherhithe and Limehouse, the boring of a 5ft-high pilot tunnel on the south bank starting in August 1807.

They reached the low tide mark on the north shore six months later, but the project was abandoned with only 200ft to go due to problems caused by quicksand and frequent flooding. In stepped Marc Brunel, who in 1018 patented a tunnelling shield which made safe excavations through water-bearing strata possible. The Duke of Wellington supported Marc Brunel’s scheme to burrow beneath the Thames.

In 1824 the Thames Tunnel Company was formed, with Brunel senior as engineer, and the first shaft was sunk at Rotherhithe on March 2, 1825. Isambard was brought in as acting resident engineer 13 months into the proceedings. On five occasions, the poisonous waters of the Thames, laden with sewage bacteria as at that stage the capital had no proper waste disposal system, broke into the tunnel workings.

Tragedy at the Thames

river bed.

Isambard was so enthusiastic about the ground-breaking project that he regularly remained in the tunnel for 36 hours at a time to supervise the work. He was inside on January 12, 1828, when floodwaters burst into the tunnel again.

Six workmen died, and history would have taken a turn for the worse had the same fate befallen Isambard. However, a miracle saw a massive wave of floodwater carry him up to the top of the 42ft Rotherhithe shaft and the safety of dry land. The accident led to the tunnel works going on hold for several years (it was finally opened on March 25, 1843, the day after Marc Brunel was knighted by Queen Victoria), and although he had lived to tell the tale, Isambard was severely injured.

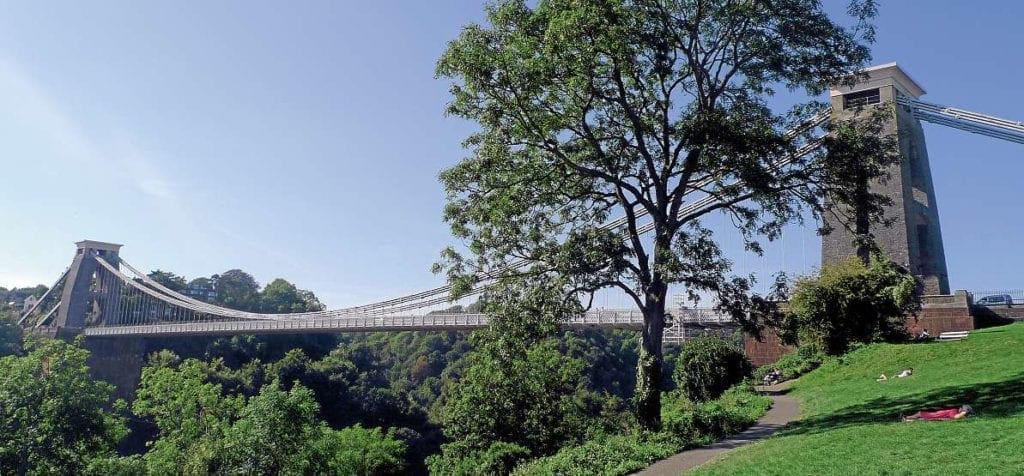

He spent several months convalescing in Brighton, but his doctors were concerned that he was not recovering as quickly as he should. Sources blamed this fact on ‘exertions with actresses’, and so it was decided to send him to a more sedate and refined location where such distractions would not be as readily available. Clifton, the genteel western suburb of Bristol, was chosen.

One of the oldest and most affluent areas of the city, with many fine Georgian houses, much of it was constructed with profits from tobacco and the slave trade. In 1676, the Merchant Venturers acquired the Manor of Clifton including 220 acres of Clifton Down bordering the Avon Gorge. Two centuries later, the neighbouring Manor of Henbury, which included Durdham Down, came on the market.

The Venturers agreed with the Corporation of Bristol that if the latter bought this land, the pair would join forces to dedicate 440 acres for the use and enjoyment of the citizens of Bristol in perpetuity. Clifton Down and Durdham Down are a much-loved beauty spot next to the suspension bridge. Under the provisions of the Clifton and Durdham Downs Act 1861 the Downs are still administered by a Downs Committee appointed in equal numbers by the city council and the Venturers. Clifton itself was formally incorporated into the city in the 1830s.

Clifton Bridge

It was at Clifton in 1829 that Isambard entered a competition to build a bridge to span the gorge, as described in the last chapter. His contributions to the Thames Tunnel and his plans for the Clifton bridge – both of which were then far from complete – earned Isambard election as a Fellow of the Royal Society on June 10, 1830, at the age of 24.

However, he still had to earn a living wage. He drained marshland at Tollesbury in Essex and then designed Monkwearmouth’s North Dock, on which work began in 1838. Eager to see what all the international fuss was about, on December 5, 1831, Isambard took a trip on the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, but unlike most other passengers, remained unimpressed.

He knew he could do better. In his notebook, he wrote: “I record this specimen of the shaking on Manchester railway. The time is not far off when we shall be able to take our coffee and write while going noiselessly and smoothly at 45mph – let me try.” He also visited the Stockton & Darlington Railway, which opened in 1825 as the world’s first steam-hauled public line. Nicholas Roch, who was also enlisted alongside Isambard as a special constable during the aforementioned Reform Bill riots, sat on the Committee for Bristol Docks.

The Reform Act, which enlarged the vote and was welcomed by city dwellers, was passed in 1832, leading to a renewed confidence in both Bristol and the national economy. Funding became available to improve the Floating Harbour, and Roch recommended the appointment of Isambard, who advised on the installation of sluices and an underfall dam for regulating water inflow and scouring silt.

Bristol’s first railway schemes

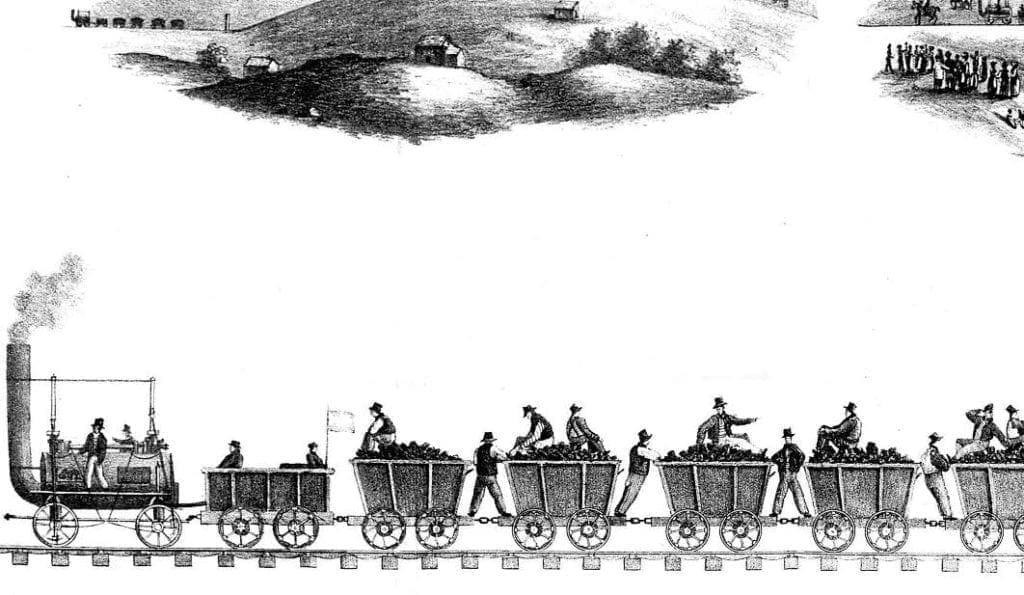

The railway concept had been around since the time of ancient Greece, and itself formed a backbone of the Industrial Revolution, with horse and man-worked tramways laid both underground in mines and on the surface to carry coal and extracted ore to the nearest transhipment point, usually a navigable waterway or harbour.

These pre-steam era early railways, tramways and plateways were laid purely to serve local concerns. One such line was the 10- mile Bristol & Gloucestershire Railway which, opened throughout in 1835, linked collieries near Coalpit Heath with the River Avon at Bristol using horse traction.

However, with the invention of the steam railway locomotive by Richard Trevithick and its first public demonstration in 1804, thoughts of a few visionaries turned towards the idea of a national network of railways. English lawyer, surveyor, land agent and pioneer rail promoter William James, a man grossly overlooked by history in favour of contemporaries like the Stephensons, originally came up with the idea of a railway linking Liverpool and Manchester, in 1822.

He surveyed other lines at a time when the idea of cross-country railways was generally considered absurd. During the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, he wrote to the Prince Regent proposing a rail link between the two principal naval dockyards at Chatham and Portsmouth which in peacetime could be used for passenger traffic.

In 1820, he promoted a horse-worked Central Junction Railway from Stratford-uponAvon to Paddington, linking to the Stratford-upon-Avon Canal at Bancroft Basin which would carry goods and raw materials to and from Birmingham and the Black Country. Only part of the line was ever built, the Stratford & Moreton Tramway.

These ideas came after that proposed by Dr John Anderson, who drew up plans for a horse worked line along the main road from Bristol to London as early as 1800, but nothing came of it. In December 1824, plans by the London and Bristol Railroad Company were published.

Its route was surveyed by John Loudon McAdam, the famous road engineer whose name was adopted for road surfacing material, and ran through Mangotsfield, Marshfield, Wootton Bassett, and the Vale of White Horse to Wantage and Wallingford, and from there to London, either via Reading or an alternative route on the south bank of the Thames. McAdam chose the flattest route possible.

It stalled, as did a plan by Francis Fortunes for a General Junction Railroad from London to Bristol, and a London to Reading scheme backed by Kennet & Avon Canal shareholders the following year. The lack of interest changed with the opening and meteoric rise of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway.

At the same time, it was noted that the canal link between Bristol and London was not always reliable: in hot weather, low water levels could strand boats, and in winter, frost and floods hampered traffic. When boats could not pass, goods had to be transferred to road at huge cost. Proposals for a Bristol & London Railway, quickly changed to London & Bristol Railway, appeared in May 1832, with a direct but hilly route via Bath, Bradford-on-Avon, Trowbridge, Devizes, Hungerford, Newbury and Reading. The survey was undertaken by William Brunton and Henry Price. Yet again, the necessary finance was not made available.

However, that autumn, four Bristol businessmen, George Jones and William Harford, who were directors of the Bristol & Gloucestershire Railway, sugar refiner Thomas Guppy (a close friend of Isambard) and chemist William Tothill, met in an office in Temple Becks and formed a railway committee. They then proceeded to muster up sufficient support among city merchants and financiers.

On January 21, 1833, a meeting was held between the Merchant Venturers, who had supported Isambard over the suspension bridge project, Bristol Corporation, the Bristol Dock Company, the Chamber of Commerce and the Bristol & Gloucestershire Rail Road Company to look at such a scheme. Agreement was reached to fund a survey of the route, and Roch was asked to find an engineer. That was not an easy task if the formative days of railways, when they were very thin on the ground.

Roch alerted his friend Isambard to the project, and he and several rivals including Brunton and Price, along with William Townsend, who had built the Bristol & Gloucestershire Railway, were invited to find the cheapest route. Brazenly, Isambard, then only 27, told the railway committee that despite the false starts of the third part of a century, he would not build a railway on the cheap.

He said he would either be given the scope to build the best railway of them all, or was not interested. He called their bluff, and won the day… but only by a single vote.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel was appointed as engineer to what soon became known as the Great Western Railway.

September 15, 2022 marks 163 years since Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s death.

The above feature is an extract from the book Brunel’s Big Railway – available on AllMyReads now!

For the first half of the 20th century, the Great Western Railway, otherwise known as God’s Wonderful Railway, stood high above the rest as an international byword for excellence in the field of transport technology.

From day one, a visionary screaming to get out, Isambard Kingdom Brunel coloured his technological prowess with a taste for classical architecture, uniquely improving the cities, towns and landscapes through which his railway ran with his buildings and infrastructure. Never mind the budget: Brunel was going to have the best, and it showed.