The 1930s were the golden age of the ‘Big Four’ railway companies that arose from the Railway Act of 1921 following the experience of placing the country’s many diverse railway companies under government control during the First World War.

By the time the London, Midland and Scottish Railway, London and North Eastern Railway, Great Western Railway and Southern Railway were born on January 1, 1923, the total UK rail network had grown to a staggering route mileage of almost 19,600.

Among the constituent companies forming the LMS were the London and North Western Railway (which exactly a year earlier had amalgamated with the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway), the Midland Railway, the Caledonian Railway, the Glasgow and South Western Railway, the Highland Railway, the Furness Railway and the North Staffordshire Railway, not to mention Ireland’s Northern Counties Committee.

The new company found itself with more than 7000 route miles and well over 10,000 steam locomotives from 393 classes, many of them dating back to the last decades of the 19th century, so a serious programme of standard class locomotive-building was sorely needed.

This did not happen, though, until the appointment of William Stanier from the Great Western Railway as Chief Mechanical Engineer in 1932, for he was preceded in the post by George Hughes from the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (1923-25), Sir Henry Fowler from the Midland Railway (1925-31) and Sir Ernest Lemon (1931-32).

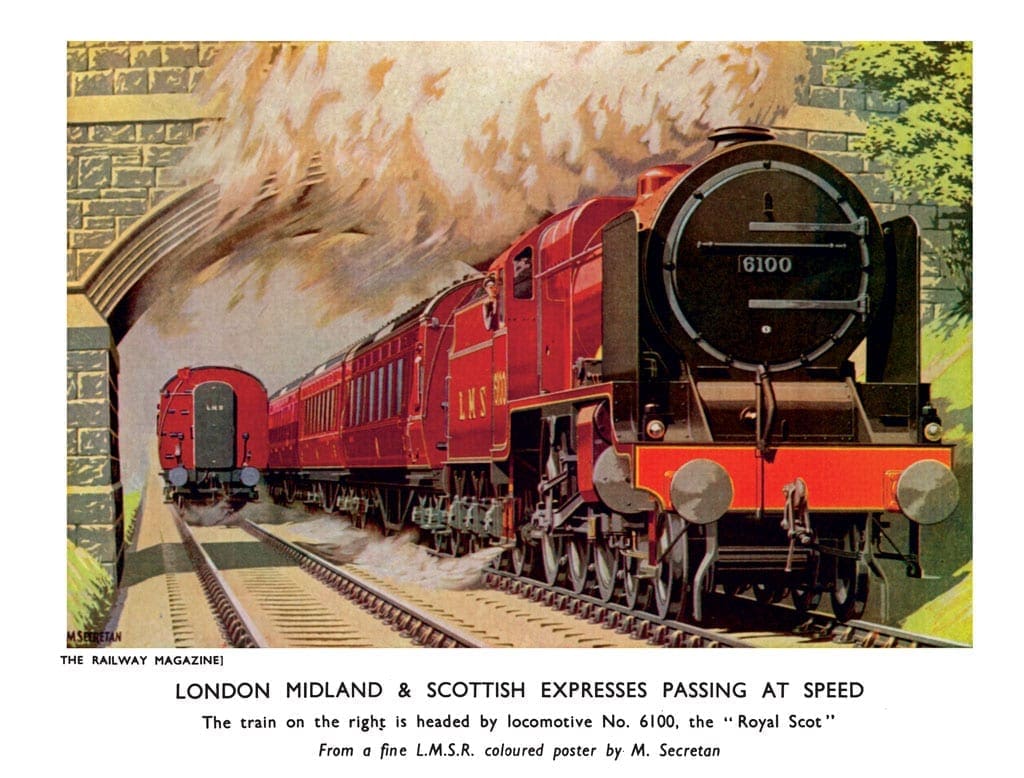

Fowler did, however, introduce some much-needed new motive power to the LMS, including the parallel-boiler, three-cylinder express passenger ‘Royal Scot’ 4-6-0s that were introduced in 1927, and the smaller ‘Baby Scot’ (or ‘Patriot’) 4-6-0s in 1930.

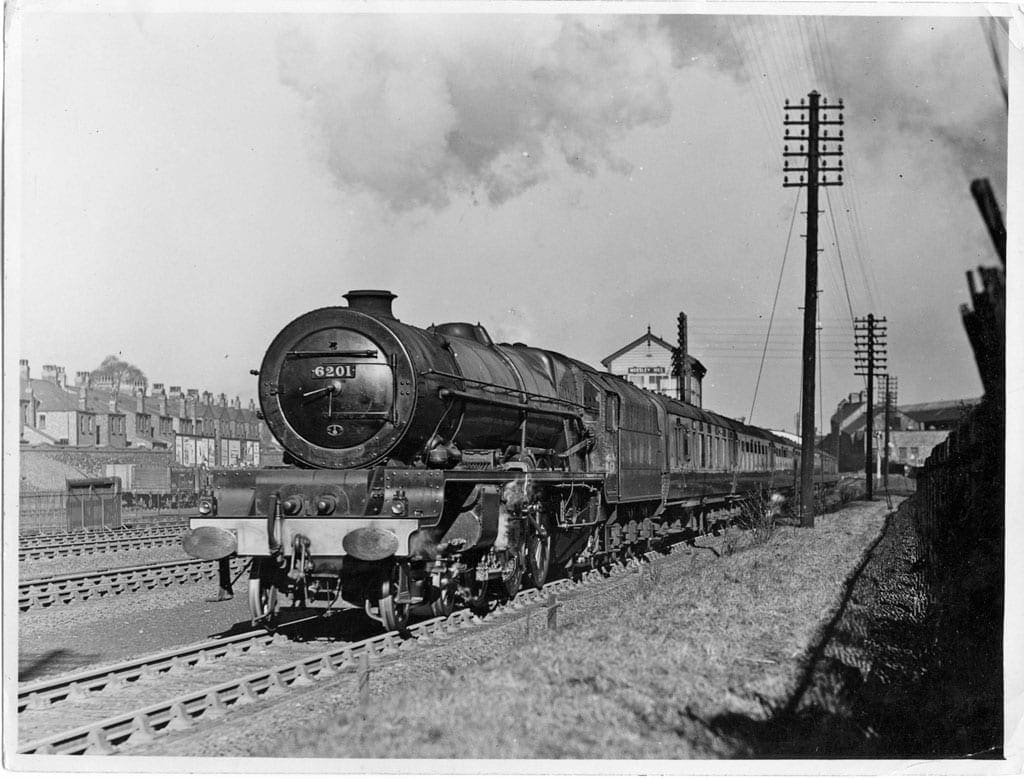

Stanier and his drawing office team wasted no time in transforming the face of the LMS by introducing thousands of modern, capable locomotives. The programme began in 1933 with his two-cylinder, taper-boiler 2-6-0s (the first of which even sported a GWR-style top feed cover!) and ‘Princess Royal’ Pacifics. Other notable new classes were the three-cylinder ‘Jubilee’ 4-6-0s of 1934 and the mighty ‘Princess Coronation’ Pacifics of 1937.

Perhaps the two most important designs of all, though, were the versatile mixed-traffic ‘Black Five’ 4-6-0ss, built between 1934 and 1951 and eventually numbering 842 examples, and the freight equivalent, the 8F 2-8-0s of 1935.

Although only 126 8Fs had been built by the outbreak of war in 1939, the numbers were massively boosted when the design was adopted as a national standard engine for war service until eventually succeeded by the cheaper WD 2-8-0 ‘Austerities’ (and a number of similarly-styled 2-10-0s) in 1943.

Among the main constituent companies forming the LNER were the Great Northern Railway, the North Eastern Railway, the Great Eastern Railway, the Great Central Railway, the Hull and Barnsley Railway, the North British Railway and the Great North of Scotland Railway.

Unlike the LMS though, the appointment of Nigel Gresley as the LNER’s Chief Mechanical Engineer from his similar post at the Great Northern Railway brought a vital continuation that would earn the newly-founded company a richly-deserved reputation for glamour and speed.

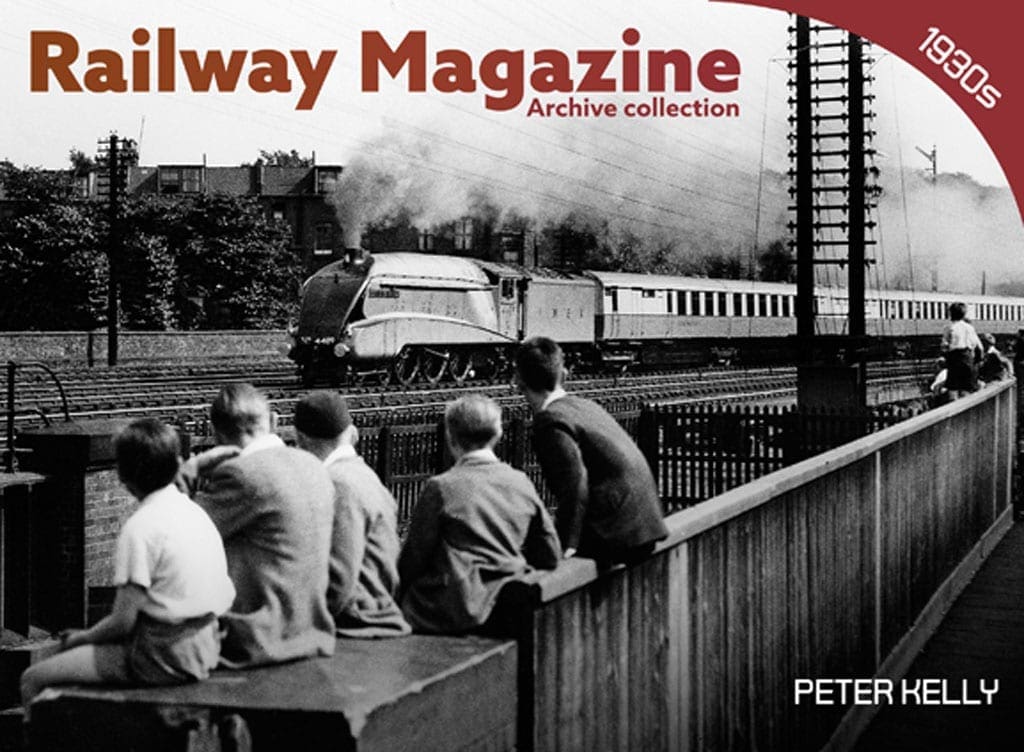

Gresley’s hand was seen in many sleek and efficient express locomotive designs, including the A3 Pacifics, the V2 2-6-2s, the mighty P2 2-8-2s and of course his crowning glory, the streamlined A4 Pacifics that launched the superb art deco-styled King’s Cross to Newcastle ‘Silver Jubilee’ express of 1935 (in a trial run for which No. 2509 Silver Link attained a record-breaking speed of 112 mph).

In 1937, the King’s Cross to Edinburgh ‘Coronation’ brought yet more excitement, and to top it all, in a challenge to a briefly-held German steam speed record of 125 mph, A4 Pacific Mallard attained the still-standing world record for steam of 126mph on July 3 1938.

At the Grouping, the LNER’s rail network stretched to 6590 miles, and even though some two-thirds of its income came from freight, its main image to this day remains one of glamour.

In comparison to these two giants, the remaining members of the ‘Big Four’, the Great Western Railway and the Southern Railway inherited route mileages of just 3800 and 2186 respectively.

The GWR, whose identity remained largely unchanged, absorbed a large number of relatively small concerns including Cambrian Railways (along with the narrow-gauge Vale of Rheidol and Welshpool and Llanfair lines), the Alexandra (Newport & South Wales) Docks & Railway, the Barry Railway, the Brecon & Merthyr Railway, the Burry Port & Gwendraeth Valley Railway, the Cardiff Railway, the Rhymney Railway and the Taff Vale Railway.

From the birth of the ‘Big Four’ and right through until 1941, the Great Western Railway’s Chief Mechanical Engineer was Charles B Collett, who had succeeded the great George Jackson Churchward. Collett and his team successfully introduced many fast, modern locomotives including the four-cylinder ‘Castle’ and ‘King’ 4-6-0s, the two-cylinder ‘Hall’ and ‘Grange’ 4-6-0s, the delightful 1400 Class 0-4-2 tank engines for branch-line work and a number of versatile prairie and pannier tank classes.

Even Gresley learned valuable lessons following the sure-footed trial running of a ‘Castle’ out of King’s Cross in the 1920s, and at the Grouping, the Great Western Railway was the most standardised company of the ‘Big Four’, to all intents and purposes carrying on as if nothing much had really happened – and this unique identity continued even into British Railways days.

The Southern Railway differed from the others in that its main business was passenger rather than freight traffic, but at the Grouping, despite its massive commitment to electrification, it found itself with a diverse range of steam locomotives and rolling stock from the companies it had absorbed, including the London & South Western Railway, the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway, the South Eastern Railway and the South Eastern & Chatham Railway, which had been formed in 1899 as a working union between the South Eastern Railway and the London Chatham & Dover Railway.

The SR’s first of only two Chief Mechanical Engineers was the Dublin-born Richard Edward Lloyd Maunsell, who retained the post he’d held at the South Eastern & Chatham Railway, and Oliver Bulleid from the LNER who succeeded him in 1937.

Among Maunsell’s outstanding contributions to the newly-formed company were the four-cylinder ‘Lord Nelson’ 4-6-0s that uniquely produced eight exhaust beats to the bar and found plenty of work on heavy boat trains. Many ‘King Arthur’ 4-6-0s were also built during Maunsell’s watch, and his three-cylinder V-class ‘Schools’ 4-4-0s became the most powerful of their type in Britain.

The U and U1 2-6-0s, Z class 0-8-0 shunters and W class 2-6-4 tank locomotives were also designed and built under Maunsell, whose name, incidentally, should be pronounced ‘Mansell’.

As many photographs in this book show, the 1930s was a decade of bold experimentation in the search for more efficient steam motive power, and the introduction of modern standard locomotives, the benefits of which had already been amply demonstrated by the GWR.

Among the memorable designs were Gresley’s 4-6-4 four-cylinder compound No. 10000, featuring a modified Yarrow-built marine-type water-tube boiler working at an ultra-high pressure of 450lb, which emerged from Darlington Works in 1929, and Stanier’s steam-turbine ‘Turbomotive’ No. 6202, the third of his ‘Princess Royal’ class, which featured a long forward turbine on one side and a short reversing turbine on the other.

Introduced in 1934 to handle the heaviest passenger trains without the need for double-heading on the difficult line between Edinburgh and Aberdeen, another of Gresley’s masterpieces was the three-cylinder P2. Six of these gigantic 2-8-2 locomotives were built, featuring 6ft 2in driving wheels and massive boilers, but only nine years later they were rebuilt by Gresley’s successor Edward Thompson as not very attractive-looking A2/2 Pacifics.

The sleek A4 Pacifics of the LNER and ‘Princess Coronation’ Pacifics of the LMS were the outstanding symbols of an all-too-brief ‘streamlined age’ that was cut short by war in 1939, but even though the GWR ‘Castles’ could show a clean pair of heels to most locomotives without the need for any tinwork, one of the most bizarre attempts at streamlining appeared on No. 5005 Manorbier Castle in 1935. This consisted of a bulbous smokebox door cover, shrouds around the outside cylinders and buffer beam and fairings behind the chimney and safety-valve bonnet, and from the bottom of the cab front right along the running plate.

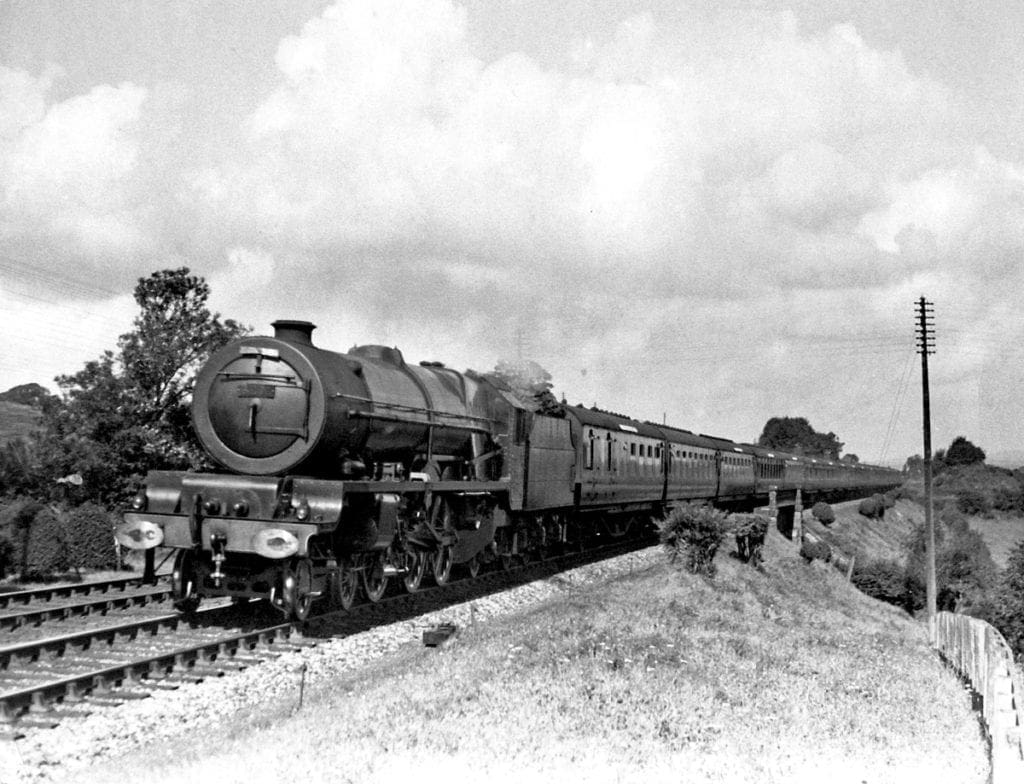

While it’s all too easy to become carried away by the exciting locomotive developments of the 1930s, many of our photographs show that throughout this period, countless pre-grouping locomotives of every kind, many dating from the 19th century, continued to battle on gamely with passenger and goods trains alike.

Many pre-grouping classes toiled away on coal trains for the rest of their days, while large-wheeled 4-4-0s and Atlantics continued their high-stepping ways on express trains, increasingly so as pilot engines.

Throughout the 1930, locomotives such as the Great Western ‘Bulldog 4-4-0s’, London and North Western Railway ‘Claughton’ 4-6-0s, South Eastern and Chatham Railway Wainwright D 4-4-0s, Highland Railway ‘Castle’ 4-6-0s, Great Northern Railway Atlantics (4-4-2s) and locomotives of a similar wheel arrangements from the London, Brighton and South Coast, Great Northern, Great Eastern, Great Central and North British Railways could still be seen at work on passenger duties, while a plethora of venerable smaller engines continued to work on branch lines, in shunting yards and as station pilots.

Goods and mineral traffic remained the bread and butter of the three biggest ‘Big Four’ constituents throughout their existence, and while the quest for express train publicity stole the 1930s headlines, it was in vast goods yards and shunting sidings that the real work went on day and night.

If you were a town or city dweller, it’s almost certain that you would have heard short whistle blasts carried on the wind and the continuous ‘clink, clank’ of loose-coupled wagons clashing together as you went upstairs to bed — noises that can still be heard, rather hauntingly, in many old black and white films.

Want to read more? Pre-order your copy of Railway Magazine Archive collection: 1930s, here.

Welcome to this first book of railway photographs from the Mortons Railway Magazine Archive, concentrating on the very eventful decade of the 1930s.

First published in London in 1897, The Railway Magazine is one of the oldest titles in the UK, and Peter Kelly was proud to be its ninth editor from 1989 until 1994. It is now produced by the Mortons Media Group of Horncastle, Lincolnshire, and remains Britain’s best-selling railway title.

After many enjoyable hours of pondering over the Mortons Railway Magazine photographic archive, (now, thankfully, digitised) Peter and Mortons archivist, Jane Skayman, have endeavoured to present a fair balance from the 1930s and hope very much that you will enjoy looking at these nostalgic images as much as they have done.